Just Another Brick in the Wall

The Higher Education system is a complete failure and the recent AI-related hiccups are simply warning signs

“The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.” George Orwell

Spirit of Halloween stores are open everywhere. You can see pumpkin spice across stores and vendors. The 2024-25 academic year has began. Next week my absolutely amazing fourteen year old son will officially become a freshman in high school. I am proud of many a thing this kid has achieved, from the distinguish honor roll to black belt in kempo karate to being a great musician on four different instruments, that’s before we even get to his character and qualities, which I could and probably should spend an entire essay on another time. Today, I want to call out that I am also proud of him for deciding already that he will be attending college or university in Europe rather than United States. The obvious reasons of course being economic, whereas he would not be burdened with upwards to a quarter million dollars of debt upon graduation from an institution that is part of an utterly failed educational system. Yes, I am speaking of the once proud colleges and universities in the good ol'e United States.

I’ve written about how the American secondary education has quickly aligned itself with the far-right and essentially drowned student protests in the spring with onslaught of militarized fascism. The new academic year is not any better. Many institutions announced their staunch stance on neutrality regarding politics while ensuring to take any discussion of divestment off of the proverbial table. University administrations ARE taking a political side while claiming neutrality and it is pure greed.

What caught my eye in recent days is the absolute shitshow across campuses in terms of using Artificial Intelligence (AI), specifically ChatGPT, Claude, and similar Large Language Models (LLMs). Yesterday, I learned that the APA, Chicago, and MLA have all established a new citation standard for ChatGPT generated text. This new “standard” prescribes putting the company name behind the generator (e.g. ChatGPT, OpenAI) and the date you generated it counts, even though the text is not replicable or searchable. In other words, you literally cannot find or verify the text being cited even with the exact same prompt, because ChatGPT just plagiarizes different texts the next time it generates you a response. Craig Gallagher, Professor of History, summarized this perfectly: “What are we doing here? Never has the decline in critical thinking or media literacy in the West been more apparent than in the total absence of scrutiny these profoundly bunk generative technologies have faced.” As another, anonymous, PhD says “If you’re going to cite ChatGPT the correct citation is just “a hallucinating plagiarism machine that is cooking the planet” followed by the date on which you used that hallucinating plagiarism machine that is cooking the planet.”

Galen Bunting, who teaches at Northeastern is absolutely right saying “why I ban writing with Large Language Models in my writing classes:”

The response from the tech bros, is of course, very predictable. “I understand your intention but think you’re overlooking the value of LLMs as conversational tools. Instead of banning them, use them differently. Rather than having a student submit one LLM-generated piece, have them create 10 with varied prompts.” Except a writing class is not meant to teach student how to learn prompt engineering and neither the professor nor the student should be interested in such an outcome from a writing class.

The other day I engaged in a quick debate with a self-described AI-doomer on Twitter who caused a minor stir proclaiming that “properly using ChatGPT is better […] than most humanities professors are.”

Mind you, this person is a professor at an accredited institution who is teaching students!! Ted Chiang in the New Yorker perfectly explains this:

Here’s another example from Megan Fritts, professor of Philosophy at University of Arkansas:

“Second week of the semester and I've already had students use (and own up to using) ChatGPT to write their first assignment: "briefly introduce yourself and say what you're hoping to get out of this class". They are also using it to word the *questions they ask in class*. At this point LLMs-in-the-classroom apologists should be embarrassed. Students aren't just using this stuff as a "problem solving tool" or whatever BS people spout, they're using it to forget how to talk. Impossible to be pessimistic enough about it tbh.”

The BS that Megan mentions is likely crap like this. I haven’t spent too much time looking for the justification for use of AI in colleges, but I am sure it’s all the same. More than a year ago, Jennifer Harmon, another professor, admitted that it’s worse that she thought. I am with her. It is a lot worse than I thought. Yes, schools are adapting guidelines and guardrails for use of AI in the classrooms, but at best it’s a cop out that passes the proverbial buck onto the teachers: “Course policies regarding the use of generative AI are best adapted to the local context of the course, including the instructor’s expertise and perspectives; the course learning goals; the nature of the coursework, discipline and/or profession; and the learning needs of the students.“

Many decades ago, I was a student at a university myself and those days of early adoption of personal computers (PC), I quickly discovered that with enough technical know-how, knowledge and expertise on specific subjects, experience with professors and general ability to write well I could easily make a decent enough living by writing essays and reports for others, eventually growing my “library” of such enough that I could easily plug-n-play individual modules of content to create a unique coherent essay tailored to a specific professor without a hint of any past work being submitted to the same professor. I’ve always prefaced my work with a disclaimer that the following text was written by me and given to such and such student as part of an educational exercise within the framework of a tutoring session. What the student did with that, was none of my business. If my Alma Mater wants to rescind my diplomas for violations of the ethic code, I would recommend that they first look through hundreds of diplomas given to students who did not earn them at all and then take a look at promoting a business centered on the idea of taking very detailed and accurate notes for practically any class and then selling these through an actual store front on the main street on campus.

Universities have no answers to the LLM cheating problem. Just like they did not have answers to any other cheating trends in the past. Our institutions have invested no substantive time finding solutions, and some have actively championed the fully braindead idea that LLMs are “learning tools.” Instead, everyone blames students for being “lazy.” At the end of the day, the institutions simply don’t care as long as they make profit, for that’s all that they have become, an extension of the corporate world ruled by pure greed. Stanford tried to explore what AI chatbots really mean for students and cheating almost a year ago. There’s even somewhat reasonable set of recommendations why universities need to adopt an AI acceptable use policy: “that using AI programs for clarification, explanations, ideation and topic suggestions is allowed.”

Yet, any policy or set of guidelines would be nothing more than a Band-Aid solutions. Universities could not really keep up in the pre-digital age, now as Elbert Hubbard puts it “the world is moving so fast these days that the man who says it can’t be done is generally interrupted by someone doing it” there is a better chance for a snowball in Hell then any policy or rule that will prevent use of AI to cheat or avoid actual learning.

The problem is not with students being lazy, it’s not even with AI, but with how much over the last few decades our higher education campuses have been weakened as actual communities, communities of learning, where people mingle, interact and get to know and trust each other. Because, our higher education institutions have been deteriorates from educational centers to moneymaking schemes for profit.

Instead of investing in actual education, year after year we have witnessed more and more faculty roles being reduced. The above example from Dr. Emily Hamilton-Honey is just one of many and is not limited to that specific field of study. It’s barren across the board. Yet, at the same time as faculty is being decimated by constant rollbacks and cuts, in the current period of growing economic complexity and anxiety, we are in the midst of a massive shift of rapidly decreasing availability and opportunity for higher education at an affordable cost and/or in frictionless human-focused scaleable delivery for an average American, not to mention the colossal gap of availability of higher education across the Global South and other developing nations.

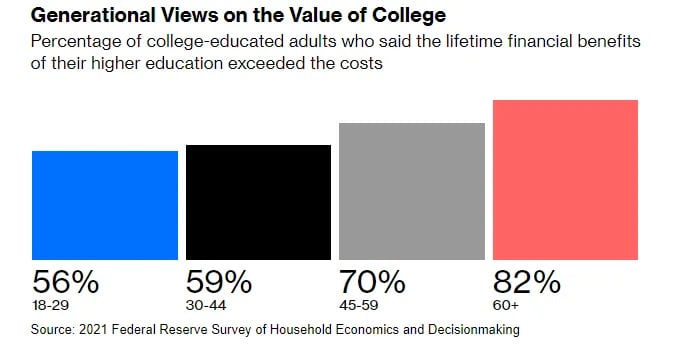

The centuries old system of higher education can no longer support the increasingly growing and rapidly more diverse needs of the population. In the US, the cost of higher education in public institutions essentially reversed from majorly funded by public money with low tuition costs to now mostly funded by escalating and often prohibitive tuition and fees (and for many, room and board) with austerity and pandemic related cost cutting decreasing public funding.

The average cost of attending a public 4 year school in the US now exceeds $20,000. According to U.S. News data, the average cost of tuition and fees for the 2022-2023 year at ranked public colleges was $10,423 for in-state students and $39,723 at private colleges. For the same year, the average cost for out-of-state students at public colleges was $22,953.Graduates from the class of 2021 who took out student loans borrowed $29,719 on average, according to data reported to U.S. News by 1,047 colleges in an annual survey. That's a 25% increase over 2009 in the amount students borrowed.

Across the U.S., 32 states spent less on public colleges and universities in 2020 than in 2008, with an average decline of over $1,500 per student. For example, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, between 2008 and 2018, the two states that made the biggest cuts to higher-ed funding were Arizona and Louisiana. Meanwhile, the two states that saw the biggest tuition increases over those years were… also Arizona and Louisiana. In Arizona, tuition increased an average of $5,384 per student during that time; in Louisiana, it increased by $4,810.As a result, students need to pay (and borrow) more. But that's not the whole problem: Institutions also are spending more on things that don't have to do with student learning, such as student services, institutional support, etc.

The byzantine and oftentimes purposely confusing student loan system contributes significantly to the growing financial inability to afford higher education. Despite recent efforts by the Biden administration, student loans are still a barrier to higher education and the fascist clique is desperately trying to prevent or rollback these ongoing efforts. Too many students can’t afford to go to college and pursue their career dreams, and too many who do are sentenced to a lifetime of debt. This is especially true for students who might be the first in their families to attend college.

Faculty also pays for funding cuts. Between 2020 and 2021, NEA research shows that faculty salaries, corrected for inflation, fell by 1.6 percent, while state funding fell 1.3 percent. This makes it difficult to retain high-quality faculty.

It used to be that “state university” meant a university was largely funded by the state, for the benefit of the state. In fact, back in 2008, U.S. states spent an average $8,823 per college or university student, NEA’s research shows. Then, the Great Recession struck, and state revenues dried up. In just one year, state funding decreased by about $2,000 per student. Colleges and universities rushed to fill the gap with tuition increases—and, for the most part, students are still paying the lion’s share today, even though many can’t afford it. Take Alabama, for example. In 2008, the “student share” of college revenues was about 40 percent. Today, nearly $7 out of $10 dollars going into the public college system comes from students, who often borrow to cover the cost. “Alabama has a lot of low-income people, but our tuition revenue is twice the national average,” noted Alabama Commission on Higher Education Executive Director Jim Purcell to the Alabama Daily News. And Alabama is far from alone. State funding comprises a mere 4.3 percent of the budget at the University of Colorado Boulder and 8.6 percent of the University of Virginia’s academic budget. (With scant state funds available, it’s not surprising that Virginia’s George Mason University has accepted millions of dollars—with strings attached—from the conversative Charles Koch Foundation.)

Furthermore, the recent protests across university and college campuses in support of Gaza, stripped away any remaining pretense that our higher education system is no longer based around actual communities of knowledge, where people interact, share ideas and learn, because our higher education institutions have been turned into for-profit corporate shills. Over the years colleges shifted their endowments from low risk to private equity and hedge funds who were promising and delivering big returns.

Obviously, the more you invest, the more you will get in return. This meant that schools started to shift toward funding fields of study that would produce future wealthy donors - in other words NOT humanities. In theory, this should have been a positive for the schools, faculty, students, etc. Sadly, in reality, rather than spend the billions in endowments on financial aid, lowering tuition, funding faculty or staff, it is used to improve branding and rankings. Judging by the events of the past year, the role of a university or college president has evolved into more of an external de facto CEO rather than internal academic or scholar dedicated to the educational mission of the school. This is why we see a sweeping national effort to establish defense industry recruitment pipelines in college STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) programs. Dozens of campuses nationwide now have corporate partnerships with Lockheed and other weapons manufacturers. In 2020, for the first time, federal funding to Lockheed Martin surpassed that of the U.S. Department of Education, the federal agency tasked with dispensing scholarships and Pell grants.

This is a significant reason why we continue to see reports of grade inflation at elite universities with the administration doing nothing to address it. In the end, the voices of students and faculty are silenced, as it is no longer a community of learning, the focus is on the external voices of those who will fund their lavish salaries and help improve their rankings.

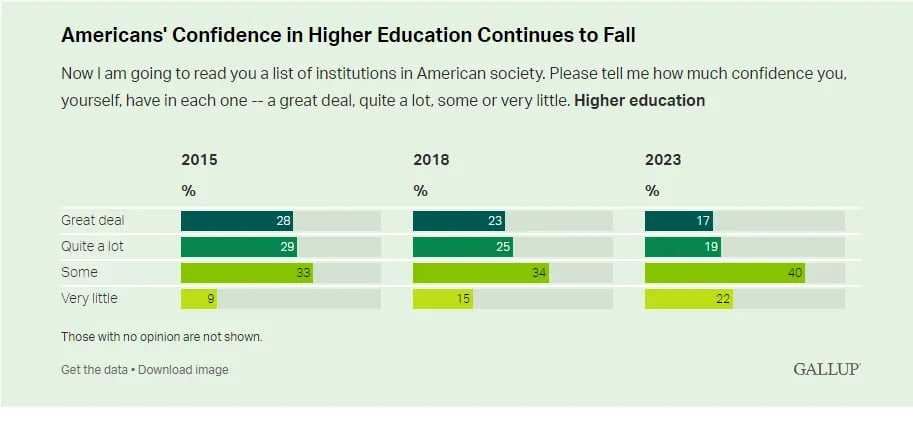

Ultimately, according to Gallup Americans’ confidence in higher education, which showed a marked decrease between 2015 (57%) and 2018 (48%), has declined even further to a new low point of 36%. While Gallup did not probe for reasons behind the recent drop in confidence, the rising costs of postsecondary education likely play a significant role.

There was a decline across all demographics in terms of the percentages of these groups that said they have a great deal or quite a lot of confidence in higher education. Survey respondents who possessed either a college or postgraduate degree were among the most likely to express confidence in higher education, and observers say that's because they've seen the value of it first-hand.

Although those with a great deal or quite a lot of confidence among the youngest group surveyed (18 to 34) has fallen 18 percentage points since 2015, a Gallup and Lumina Foundation study found that about three-quarters of current and prospective college students surveyed in fall 2022 said a college education is equally or more important than it was 20 years ago.

Enrollment has fallen by 1.4 million since the pandemic, with no end in sight with the waning of the pandemic. A majority of Americans now consider a college degree a questionable investment. The latest statistics show that 55% of today’s college and university students are Gen Zers (Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation).

In fall 2021, total undergraduate enrollment in degree-granting postsecondary institutions in the United States was 15.4 million students, 3 percent lower than in fall 2020 (15.9 million students). This continued the downward trend in undergraduate enrollment observed before the coronavirus pandemic. Overall, undergraduate enrollment was 15 percent lower in fall 2021 than in fall 2010, with 42 percent of this decline occurring during the pandemic. In contrast, total undergraduate enrollment is projected to increase by 9 percent (from 15.4 million to 16.8 million students) between 2021 and 2031.

Of the 15.4 million undergraduate students enrolled in fall 2021,

7.8 million were White;

3.3 million were Hispanic;

1.9 million were Black;

1.1 million were Asian;

663,100 were of Two or more races;

107,000 were American Indian/Alaska Native; and

41,000 were Pacific Islander.

Trends in undergraduate enrollment between fall 2010 and fall 2021 varied across racial/ethnic groups. During this period, the enrollment decreased for

American Indian/Alaska Native students (by 40 percent, from 179,100 to 107,000 students);

Pacific Islander students (by 29 percent, from 57,500 to 41,000 students);

White students (by 28 percent, from 10.9 million to 7.8 million students); and

Black students (by 27 percent, from 2.7 million to 1.9 million students).

In contrast, between fall 2010 and fall 2021, enrollment increased for

students of two or more races (by 126 percent, from 293,700 to 663,100 students);

Hispanic students (by 30 percent, from 2.6 million to 3.3 million students); and

Asian students (by 7 percent, from 1.0 million to 1.1 million students).

All racial/ethnic groups had a lower number of undergraduate students enrolled in fall 2021 than in fall 2020 or fall 2019, the year prior to the pandemic. The difference between enrollments in fall 2021 and fall 2019 ranged from less than one half of 1 percent lower for Asian students to 9 percent lower for Pacific Islander students.

Enrollments of undergraduate U.S. nonresident students in U.S. degree-granting postsecondary institutions increased by 38 percent from fall 2010 to fall 2019 (from 398,400 to 548,600), but fell during the pandemic. Nonresident undergraduate enrollment was 3 percent lower in 2021 than in 2020 (455,500 vs. 468,800) and 17 percent lower in 2021 than in 2019 (455,500 vs. 548,600).

A 2019 survey revealed that even though university leaders are aware of the significant role AI could play over the next 10-15 years, many are skeptical about its implementation. Studies show that only 41% of universities and colleges have a clear AI strategy in place. Also, cost remains a major impediment and it is, therefore, unsurprising that 57% of institutions have yet to allocate budget for AI projects (Pells, 2019). The new generation of students are accustomed to using technology from a younger age and thus are comfortable at home using tech tools to acquire knowledge and skills. Pew Research reports that 95% of GenZers have access to smartphones, whereas 97% use at least one of the major online platforms (Parker & Igielnik, 2020).

We absolutely must address the growing issue of students electing to retort to the easy way to get a good grade by subcontracting their work to AI. However, if we want our children to grow and develop and learn and become responsible, ethical and empathetic human beings we must, absolutely must address the entire system of so-called higher education as it’s neither higher nor education.