Wednesday afternoon coffee breaks

I think I'd like to try something, and need your help in figuring out if it's a good idea.

I'd like to host mini "coffee breaks" every Wednesday afternoon at 2:30pm where I'd bring together four people—ideally, people from various spheres of my life who don't know each other—on a video call and we'd spend three minutes each (for a total coffee break of fifteen minutes) telling each other a story based on a prompt that I will circulate the day on the Tuesday.

Prompts may include things like:

- Tell me a story about the best thing you've eaten this week.

- Tell me a story about a color that you noticed this week.

- Tell me a story about something that made you laugh this week.

- Tell me a story about something that made you cry this week.

- Tell me a story about an adventure that you had this week.

Those are just a few examples; I have many more. Essentially, the prompts are small ways to get to know each other a little better, even if just in three minutes. If you're interested in hearing more from the person you meet in the coffee break, I'll share contact details and you can connect.

Essentially, this is my way of trying to connect people from various parts of my life that I find fascinating and interesting, and also just check in and feel a short connection—through story and narrative—with each of you.

What I'm asking you is this: do you think this is a good idea? And if yes, would you be willing to participate? Send me an email and let me know. Thanks!

Two poems

A Slow Way

Jenny Xie

It's possible I'm tallying

wrong in this life.

Better to count down than up.

I only have to shuck off

these other minds

to reach the first mind.

The one that stores nothing.

Coming before and after.

The simplicity of it is difficult.

Suffering lies here in the open

but doesn't belong to anyone.

It migrates laterally.

A slow way—

exchanging hands.

———

To love someone long-term is to attend a thousand funerals of the people they used to be.

Heidi Priebe

The people they're too exhausted to be any longer.

The people they don't recognize inside themselves anymore.

The people they grew out of, the people they never ended up growing into.

We so badly want the people we love to get their spark back when it burns out; to become speedily found when they are lost.

But it is not our job to hold anyone accountable to the people they used to be.

It is our job to travel with them between each version and to honor what emerges along the way.

Sometimes it will be an even more luminescent flame.

Sometimes it will be a flicker that disappears and temporarily floods the room with a perfect and necessary darkness.

Some links

Urban density: confronting the distance between desire and disparity:

A quick scroll through any number of citizen-led community care groups further reveals the health concerns of those living in forgotten densities. These individuals are scared to leave their apartments for essential reasons because they can’t practice social distancing in cramped entranceways, elevators and laundry rooms. Those with underlying medical conditions are being placed at risk because families comprised of six people living in two-bedroom apartments do not have the space to quarantine within the home or the financial resources to quarantine elsewhere.

My restaurant was my life for 20 years. Does the world need it anymore?:

Everybody’s saying that restaurants won’t make it back, that we won’t survive. I imagine this is at least partly true: Not all of us will make it, and not all of us will perish. But I can’t easily discern the determining factors, even though thinking about which restaurants will survive — and why — has become an obsession these past weeks. What delusional mind-set am I in that I just do not feel that this is the end, that I find myself convinced that this is only a pause, if I want it to be?

The woman who might find us another Earth:

In some ways, the search for life is now where the search for exoplanets was 20 years ago: Common sense suggests a presence that we can’t confirm. Seager understands that we won’t know they’re out there until we more truly lay eyes on their home and see something that reminds us of ours. Maybe it’s the color blue; maybe it’s clouds; maybe, however many generations from now, it’s the orange electrical grids of alien cities, the black rectangles of their lightless Central Parks. But how could we ever begin to look that far? “Everything brave has to start somewhere,” Seager says.

All I want to do is eat alone (around other people):

I know how lucky I am to be riding out this quarantine order with someone I love who’s a great cook and spends most evenings making me inventive and comforting dishes. Hearty stir-frys, steak au poivre, pasta with tons of garlic, nicoise salad with as many eggs as I ask for—my husband can make nearly anything I’d request. His food is always perfect, a version of his love that I can devour, but sometimes, I don’t want food to be love. I just want one little solo activity, proof of my own control, a place where I can set whatever rules I want.

The pandemic doesn’t have to be this confusing:

This is how science actually works. It’s less the parade of decisive blockbuster discoveries that the press often portrays, and more a slow, erratic stumble toward ever less uncertainty. “Our understanding oscillates at first, but converges on an answer,” says Natalie Dean, a statistician at the University of Florida. “That’s the normal scientific process, but it looks jarring to people who aren’t used to it.”

The nude selfie is now high art:

There has always been a subterranean culture of salacious communication, from love letters to fiction to erotic imagery added to manuscripts, as a way of escaping the constraints of reality.

'Allostatic load' is the psychological reason for our pandemic brain fog:

In my regular life, I would see dozens of people a day. I commute to work, I get lunch, I meet up with friends, I go to the gym—and all of those little interactions are cues to my brain that I’m OK, and part of a larger social network. But when I’m alone, I’m more vulnerable, and my brain is working overtime trying to protect me.

This state says it has a ‘feminist economic recovery plan’:

A universal basic income. Special emergency funds for marginalized groups, including undocumented immigrant women, domestic workers, women with disabilities and sex-trafficking survivors. Waived co-payments for covid-19 tests and treatment, including for incarcerated women. A 20 percent pro rata share of the covid-19 response funds the express recovery needs of the indigenous population. A $24.80/hour minimum wage for single mothers. Free, publicly-funded child care for all essential workers.

None of these proposals have come from the federal government. These proposals instead come out of Hawaii, the first state to propose a what it’s calling a “feminist economic recovery plan.” Rather than restoring the economy to the old normal, the state is looking to seize the opportunity “to build a system that is capable of delivering gender equality.”

The routines that keep us sane:

Not only do routines allow us to substitute habit for willpower and put crucial chunks of the day on autopilot (freeing the mind, as James once noted in his diary, to “advance to really interesting fields of action”); they naturally create and enforce boundaries between work and home, between our professional and private selves. They are also emotional regulators. For the moodier souls among us, routines create a well-worn groove for our mental energies and prevent squalls of anxiety, irritation, or sheer indolence from dominating our days.

Stop publicly defending your friends:

Confusingly, people can be kind to us and cruel to others, especially when they do not look or sound or believe like us. There is no hard and fast rule that if someone is good to us, they are good to everyone in just the same way. Our friend’s flippant joke to a female colleague may carry a dark edge of misogynist disdain even if he helped our son get into his dream school. Our friend might dehumanize and assault a girl at some party even if he has always been a perfect gentleman with us.

We are not all in this together:

When you hear people say, “We’re all in this together,” it’s important to clarify who is included in the “we.” Why? Claiming a common experience where none exists is first the enemy of solidarity.

My father chose a white bride, which is key to the shape of his life, my mother’s, and our entire branch of the family tree. He was the first-born son. Traditionally, a prodigal Indian man returns to his father’s house on the understanding he will marry and continue to live with his parents, plowing whatever investment has been made in his education back into the household. To escape, to buck convention, to follow one’s individualized dreams is perfectly reasonable in the West, even recommended. But in Indian culture it’s a bit like embezzling your parents’ retirement savings to buy a red Mercedes convertible, which by the way is the car my father still drives, pretty unstoppably, at the age of 83.

How to evolve past capitalism:

Much like the transition from feudalism to capitalism, Wright believes, the transition from capitalism to postcapitalism must involve a gradual erosion of capitalism through invasive species and the conditions that allow these species to flourish. That is, the transition must involve moves from below (resisting and escaping) and moves from above (dismantling and taming). The end result is socialism.

A cup of tea is a hot, wet, aromatic Swiss army knife:

The best things in life – people, places, ideas or things – are adaptable. That is the thing about tea, too: it is a hot, wet, aromatic Swiss army knife, appropriate in many situations. The popular imagination is au fait with tea as a comforter, of course. (How do teachers of English as a second language convey that “I’ll stick the kettle on” means so much more?) I’ve even had a policewoman make me tea in my own home.

Even what was beyond us / was recast in our image:

Viruses do not discriminate but society does.

Who we police and who we coddle and who we condemn and who we praise and who we see and who we render invisible—those are decisions.

Society is us. Decisions don’t make themselves.

How cafes, bars, gyms, barbershops and other 'third places' create our social fabric:

If public spaces expand our social relationships and liberalize our world view, third places anchor us to a community where we are recognized and our needs accommodated. Third places are predictable and comfortable – a setting where we feel “at home.”

What was NorthPark like last weekend?:

I try on a drapey gold dress that looked very pretty on the mannequin and looks absurd on me, because I am seven inches shorter than the mannequin. Decent question: What am I doing right now? Where do I think I’m going to wear this drapey golden dress? Who goes shopping during a pandemic? Except shopping has always been a kind of dreaming. It was a story you were telling yourself about a trip you were going to take, a meal you were going to have, a life you were going to live. One day.

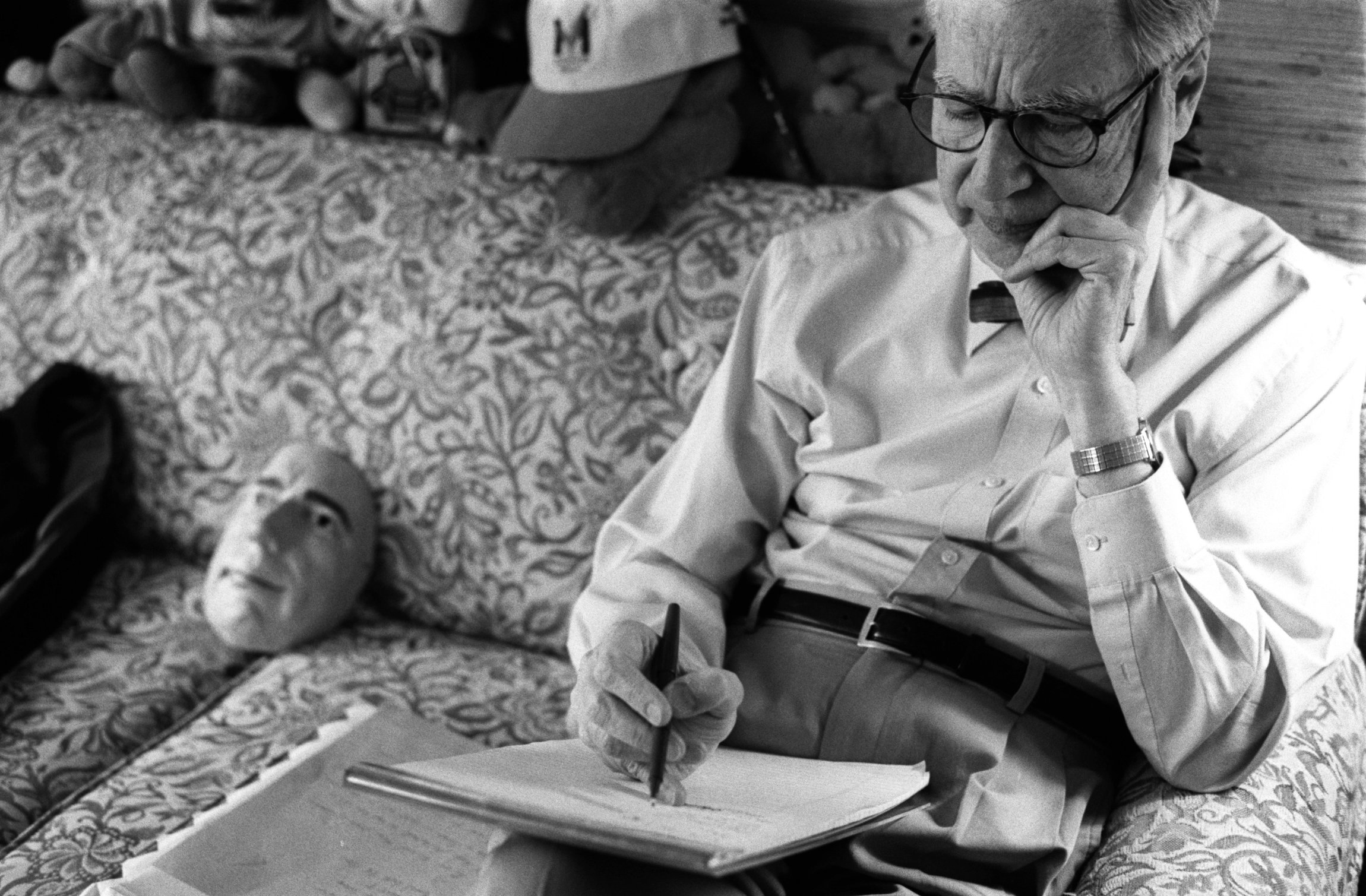

These photos of Fred Rogers off the set are just beautiful. He's one of my idols, the kind of man I aspire to be every day:

I know this is just a concept, but if they actually made these Braun Spotify players, I'd buy a few. We don't need smart speakers at home; we need Spotify radios. Gorgeous:

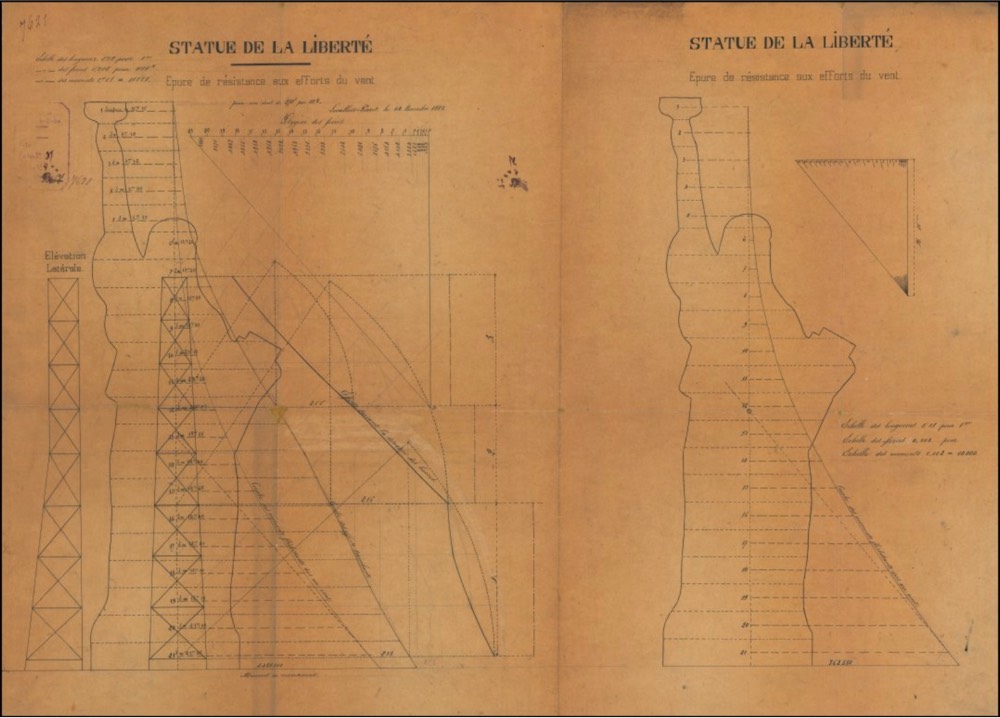

A cache of original engineering drawings and blueprints for the Statue of Liberty done by Gustave Eiffel:

Igor Leal’s ‘Buried Studio’ concept is the home office I've always wanted: