Tell your friends you love them

Tell your friends you love them when you can. You never know when you may not be able to say it again.

A close friend of mine died last month.

He was young, only a few months older than me, and like me, was a father to a young toddler. He brought so much joy into my life that I find it hard to imagine what my life would have been without him; I’m sad that I won’t get to know what the future with him would look like.

We bonded, as I do with most of my friends, over music and food. He was a connoisseur of a wide spectrum of musical styles and genres, and could slip easily between bopping his head to ‘90s hip hop to admiring the smooth saxophone tones of Coltrane. He especially loved soul music, and we would spend hours listening to, and talking about, soul and neo-soul, all while eating good food in dives across the city. He knew where to find great eats in the most unlikely of places, and he’d often lead me into small unnoticed holes-in-the-wall for excellent meals over fantastic conversation.

On Sundays, we would often watch football together. Those Sundays really weren’t about the games, but instead about finding space in our week to make sure we connected, to ensure that we were spending time with each other. We criticized the plays on the field, but we also talked about our families, our friends, our hopes, our fears, and the things that kept us excited through the days. We relished in learning about each other’s small joys and delights.

When I moved to London, our regular hang-outs stopped; the lack of proximity meant that most of our connection was done virtually, mostly through long emails that we would write to each other every few weeks. Sometimes, those weeks stretched into a month or two, but undoubtedly, I’d always find an email in my inbox when I really needed to hear from him.

It had been two months since I last heard from him before his accident, before he was taken away too soon. I still have that email he sent me, and have returned to it several times since I heard of his passing. In particular, I re-read the last few sentences he wrote me; my heart breaks every time I do:

Most importantly, something that doesn't get said enough.

I love you man.

I miss him. I really do. I am so glad to have had him in my life, and so indebted to him for helping me become the man I am now.

Tell your friends you love them when you can. You never know when you may not be able to say it again.

Two poems

Not All of Us Get to Be Ghosts

Leila Chatti

In December I watch movies about ghosts

with a woman I call mama though she is not

my mother, only a woman who is kind, this all

I require. We take breaks to lean against each other

on the porch, her sucking smoke frombetween

her fingers, exhaling its skirling; each mouthful

dissipating, becoming something like air. My breath's

a less impressive phantom, fleeting silver

in the cold light. Standing there

in our small shadows, we discuss the ways

of the dead, their metaphysics, as if we were experts

by osmosis, a certain knowledge absorbed. I say I think

our ghosts become us, or at least reside in our dark

like tenants we haven't the heart to kick out.

She says, though she hasn't quite figured it out yet,

there are rules: not all of us get to be ghosts.

Making a Fist

Naomi Shihab Nye

We forget that we are all dead men conversing with dead men.

—Jorge Luis Borges

For the first time, on the road north of Tampico,

I felt the life sliding out of me,

a drum in the desert, harder and harder to hear.

I was seven, I lay in the car

watching palm trees swirl a sickening pattern past the glass.

My stomach was a melon split wide inside my skin.

"How do you know if you are going to die?"

I begged my mother.

We had been traveling for days.

With strange confidence she answered,

"When you can no longer make a fist."

Years later I smile to think of that journey,

the borders we must cross separately,

stamped with our unanswerable woes.

I who did not die, who am still living,

still lying in the backseat behind all my questions,

clenching and opening one small hand.

Some links

Nilay captures the current state of internet really well:

Social media overall feels like when I used to go out four nights a week and drink Miller Lite until 3 am: It was cheap and fun and probably created a huge part of my personality, but, yeah, I’m too old to be doing that shit again.

Speaking of social media, it’s worth visiting our new reading environment in an era of internet upheaval:

Twitter was unproductive, depressing, and a big waste of time, but until recently it never made anyone feel quite this stupid. The Musk era has been defined by a relentless barrage of idiocy, which has seeped into the infrastructure. The sense of chaos, the eternal return of memes and controversies, the algorithmic de-emphasis on tweets that link out to anything other than tweets, the emergence of the most annoying people in new and surprising contexts (Bari Weiss and Musk: a true signature collab) — all of it is too much, especially when all one wants is interesting articles.

More about social media and how it’s shaping the way we interact:

The problem we face right now is that social-media companies can change the layout of our metaphorical town squares however and whenever they’d like, warping our public sphere in the process.

I don’t watch Succession so I didn’t get the hype about its finale, but there is a whole lot in this list of best series finales that I agree with.

I’m not usually one to take a lot of photos and let them stay in my camera roll; I’m still of the generation that is judicious about what photos I take and then cull them regularly. I wonder gems I’ve deleted from my camera roll in the past.

I went to a baseball game a couple of weeks ago and really enjoyed the pace of play despite my protestations over the pitch clock going in to the game. The pitch clock is here to stay, and I think it made the game better:

Baseball’s leisurely pace and deep patterns lend themselves to an analogous kind of contemplation, provided that those who attend the church of baseball open themselves in silence and equanimity to baseball’s contemplative dimension.

I, of course, wore my beloved Mets baseball cap to the game even though it was a Jays game, so I was quite enthralled by this history of the baseball cap as we know it.

A few great pieces about food: about revolutionizing American cheese (“American cheese is not a quality product. In fact, its lack of quality is often the point, a grand embrace of the lowbrow and cheap that is the cornerstone of so much comfort food”), revolutionizing ketchup, and how we need a bean resurgence.

I don’t have a namesake, but loved this piece about people who were named after Connie Chung.

Convenience has the ability to make other options unthinkable. Once you have used a washing machine, laundering clothes by hand seems irrational, even if it might be cheaper. After you have experienced streaming television, waiting to see a show at a prescribed hour seems silly, even a little undignified. To resist convenience — not to own a cellphone, not to use Google — has come to require a special kind of dedication that is often taken for eccentricity, if not fanaticism.

I’d venture that not many people (possibly not any people) are able to tell the difference between the top toilet cleaner and the second best — or even the fifth or sixth. This suggests that the appeal of the best is not really about a simple difference in the quality of the product, but more about a feeling: of reassurance, maybe; of having won, having got the right thing.

Doctors are rethinking how they talk to kids about weight:

A little over 20% of doctors in larger bodies said they were actively restricting calories, doing Paleo, or following another weight-loss plan, according to a 2014 survey of more than 31,000 American physicians representing 25 medical specialties. But a nearly equal percentage of doctors in thinner bodies said they were following the same kinds of eating plans, which suggests that dieting is common across the medical profession, regardless of weight status.

I’ve become an avid audiobook consumer, and it’s interesting to see how the format is changing the literary environment as a whole:

Narrators represent an entirely new role in the literary field, variously performing the functions of author, text, and reader. Like the author, the narrator is the person from whom the text emanates. Given that the material of the audiobook is not the printed page but a recording of a voice, narrators likewise serve as the embodiment of the text itself. And yet, they are also that text’s reader—in many cases, one of its very first readers. Before a book is released in hardcover, before reviews start popping up on Goodreads or in the pages of The New York Times, the audiobook is recorded. Unlike a film or television series based on a novel, the audiobook is not a post hoc adaptation but a parallel production. As a result, the audiobook narrator is often among a book’s first critics, not only reading but also doing a reading, interpreting its characters, structure, pace, and voice, in a way that shapes our own interpretations.

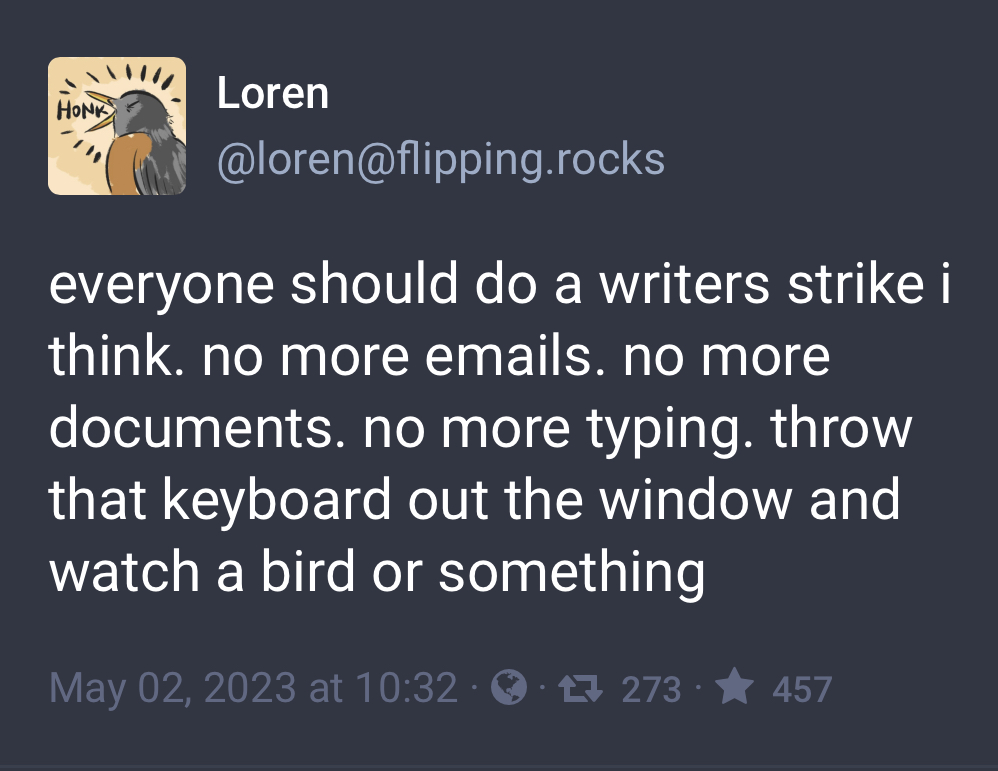

Everyone should do a writer’s strike:

Ice Merchants: a stunningly beautiful short animated film by João Gonzalez:

And a few more: