On being bursty

Someone at work remarked that I was the “fastest person in the office.” This was, of course, not meant to describe my running speed—with my knee injury and chronic back pain, running is not something I do these days—but instead my time from saying I will do something to eventually getting it done.

The secret, however, is that I am not fast at work at all, despite what it may look like from the outside. I take an immense amount of time to get anything done, but because most of the hard and slow work is invisible, my sprints to delivery seem jet-propelled.

I am bursty.

It took me a while to understand this part of my nature, something that manifests itself not just at work, but in every part of my life. I work in spurts, fast spurts, separated by prolonged periods of thought, reflection, and planning. These prolonged periods go unnoticed, but they are the most important part of my process: I can not take action on anything without time to process, without time to reflect, and without time to critically examine how any task will affect my cognitive, emotional, and mental load.

There are days I go quiet, when it feels like I haven’t done anything, haven’t delivered anything, haven’t been “productive.” In reality, those are the most important days I have; they allow me to internalize and understand, not just the task at hand, but how I feel about that task and how to approach it in a way that is authentic to my self.

And then, the burst. Once I have had time to think, to reflect, the work is quick. The time from when I _outwardly_start working on something to its completion is short, so short that I am often seen as speedy. The reality is that I spend all my time sitting at the starting line of the race, and only leave the blocks once I’m ready to sprint—when most people are already halfway down the track.

This is not how everyone works, I know—periods of deep thought, prolonged silence, and seemingly distracted activity seem counterintuitive to how we have built the modern workplace—but it is the way that works best for me. I am not the “fastest person in the office” at all, but just bursty; my speed comes from slowness, in all things I do.

It’s a slowness I embrace, I cherish, and that makes me who I am.

Poems of the week:

The Problem With Travel

Ada Limón (2015)

Every time I’m in an airport,

I think I should drastically

change my life: Kill the kid stuff,

start to act my numbers, set fire

to the clutter and creep below

the radar like an escaped canine

sneaking along the fence line.

I’d be cable-knitted to the hilt,

beautiful beyond buying, believe in

the maker and fix my problems

with prayer and property.

Then, I think of you, home

with the dog, the field full

of purple pop-ups—we’re small and

flawed, but I want to be

who I am, going where

I’m going, all over again.

from acknowledgments

Danez Smith (2018)

& how many times have you loved me without my asking?

how often have i loved a thing because you loved it?

including me

In case you missed it:

When I read, I often take notes—in the margins or in notebooks. Sometimes, I share these notes; not as book reviews, but instead as collections of thoughts inspired by the books. Here are a few “marginalia” posts I’ve shared recently:

- While reading “Becoming” by Michelle Obama, I thought a lot about the sacrifices of our parents for us to get where we are today.

- While reading “There There” by Tommy Orange, I ruminated upon the importance of voices, and of listening to voices.

- While reading “Bad Blood” by John Carreyrou, I explored the construction and distortion of reality and how that affects us all.

- While reading “Freshwater” by Akwaeke Emezi, I reflected upon how we are all made up of multitudes.

I’m starting a routine of quickly collecting some of the fun things I learn every month, and sharing them at the end of the month in a long roundup with links to the sources where you can find more information. I shared my January collection of things I learned last week.

January flew by too quickly, and in all honesty, it was a fairly miserable month. To remind myself to slow down, I re-posted my (fun, quirky) resolutions from last year.

From January to April 2019, I’m teaching the “Government in a Digital Era” course as part of the Masters of Public Service program at the University of Waterloo. Last month, I shared the course overview, and last week, I shared what we learned in Module 1—Introduction to Digital Government—with some links to student reflections, too.

A few things to read and explore:

This piece on Driving Miss Daisy, Green Book, and other interracial friendship fantasies handily proves that Wesley Morris is one of our best cultural critics writing at this time. (Also, I’m convinced we’re all going to look back at the hype of Green Book in a decade the way we look back at the confounding success of Crash all those years ago.)

“[These films] symbolize a style of American storytelling in which the wheels of interracial friendship are greased by employment, in which prolonged exposure to the black half of the duo enhances the humanity of his white, frequently racist counterpart. All the optimism of racial progress — from desegregation to integration to equality to something like true companionship — is stipulated by terms of service.”

I was taught, when I was young, that To Kill A Mockingbird was a shining example of how we can overcome racial adversity; I’m only realizing now, as I’ve gotten older, that the way we’ve taught that novel has been wrong for decades:

Students are usually surprised when I remind them that Atticus never explicitly denounces racism or impugns the characters of townspeople who revel in it. His warning that his children’s generation may have to “pay the bill” for crimes against black people smacks of fear, not hope. He stands against hate, but not, specifically, white people’s hatred of black people. Everyone has their blind spot, Atticus likes to say. Yet he proclaims to Jem that it’s “sickening” to take advantage of a black man. He places black people in the role of wayward children—ignorant, foolish, gullible. This is not an empowering message.

As I’ve been exploring issues of reconciliation and decolonization more and more recently, so this piece on publishing ‘indigenous versions’ of articles was a fascinating and eye-opening read for me:

Most fascinating to me, in all this editorial banter, was the omission of a line describing the Indigenous people living at the tent city as a demographic “literally homeless on their own homelands.” That this phrase was cut across three rigorous rounds of edit sessions typifies my struggle: I am often met with subtle condescension by decision-makers who seem to see Indigenous perspectives as advocacy-laced or, perhaps in their view, unreasonable.

I’ve spent a lot of time at work, in class, and in my personal life talking about how the inequities of justice play a large toll on communities of color. Elie Mystal’s recent opinion piece reminds us that justice is not just unequal, but it is often lethal for Black children:

Black children don’t get a PR firm and a softball interview when they are in need of redemption. They get an open casket and a good sermon when it’s time to appeal for grace.

Black children have their side of the story too, but they don’t get to go on Today and explain their actions, because they are dead. Their side of the story is left to bleed out in the street long before a compassionate white interviewer calls them for comment. A black teen exercising his right to stand there or walk there or drive there or play there or exist there can be guilty of a capital offense in this country. But a white teenager can block a national freaking monument and get a pat on the head from the president of the United States?

My friend Bianca Wylie has spoken and written a ton about how we need governments to step up and learn how to effectively regulate the data economy—and will speaking in my class on that topic in a few weeks—but this piece in the Financial Post that she wrote sums up the argument perfectly:

Over the last three decades, government, and many tech corporations, have not done the work necessary to attain social licence for their actions. They skipped a fundamental part of consumer protection; that people require education and information to make informed choices.

This is not a suggestion to make all new or potentially problematic things illegal or to destroy creative innovation. It’s a call to return to the necessary interrogation of consequences and impacts on our lives as consumers of these data products, as residents and as cities. Regulation does not kill innovation. It enables it by constructing guardrails for all of us to operate in safely, entrepreneurs included.

Don’t get me wrong: I do actually love my job, but a large part of that is not just because I get to work on things that make a real impact on real people, but because my workplace recognizes that it is just work—that I have a whole life around what I do, and work-life balance is not the goal, but instead a full life, of which work is just one part. This piece on the constant “hustle” masquerading as love of work is an important one to read:

Arguably, the technology industry started this culture of work zeal sometime around the turn of the millennium, when the likes of Google started to feed, massage and even play doctor to its employees. The perks were meant to help companies attract the best talent — and keep employees at their desks longer. It seemed enviable enough: Who wouldn’t want an employer that literally took care of your dirty laundry?

But today, as tech culture infiltrates every corner of the business world, its hymns to the virtues of relentless work remind me of nothing so much as Soviet-era propaganda, which promoted impossible-seeming feats of worker productivity to motivate the labor force. One obvious difference, of course, is that those Stakhanovite posters had an anticapitalist bent, criticizing the fat cats profiting from free enterprise. Today’s messages glorify personal profit, even if bosses and investors — not workers — are the ones capturing most of the gains. Wage growth has been essentially stagnant for years.

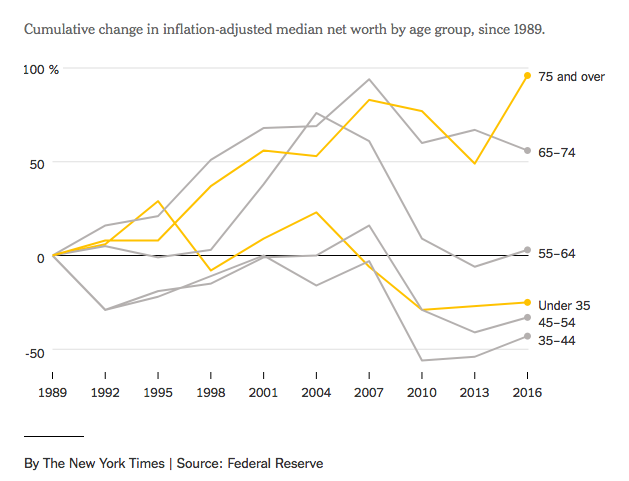

Sometimes, I wonder why—despite both L and I making decent money—I feel so financially insecure, especially compared to previous generations, and then I look at charts like these and remember that people in my age group are worse off now than they have been in decades, and realize my financial stress isn’t just imaginary.

I’ve seen patterns of these “sick systems” in various workplaces throughout my life. That’s why I’m working so hard to make sure we don’t perpetuate them in the workplace we’re building now.

After a while the stress and panic feel normal, so when you’re not riding the edge, you feel twitchy because you know that the lull doesn’t mean things are better, it means you’re not aware yet of what’s going wrong. And the system or the partner always, always obliges with a new crisis.

One thing I’m thankful for is my ability to patiently wait, to never feel like I have to be in a hurry, or to always find the fastest route, or to even fill my empty time. This rumination on waiting by Jason Fried captures my feelings on this quite well.

In the end, after all this waiting, I suspect I won’t miss anything. I’ll just have waited. In fact, I think I’ll actually find something: Additional, special moments with nothing to do. Sacred emptiness, a space free of obligation and expectation. New time to simply observe.

Last week, we recognized Bell Let’s Talk Day, and I’ve written a lot about how we don’t need one corporately-sponsored day to talk about mental health, but instead need better funding so people with mental illness can actually get the support we need. These two pieces were among the best I read that day about how to really help people, like me, who live with mental illness:

- People with mental illness don’t need more talk, Philip Moscovitch

- How to Really Talk About Mental Health, Anne Thériault

I had oat milk in my macchiato for the first time in my macchiato at a small coffee shop in Montreal late last year. It wasn’t quite the same as regular milk, so I was not smitten, but judging by the number of people asking for oat milk in their orders, I realized then that there was an “alternative milk” boon happening, and I just happened to live outside its bubble. This piece on the rise of alternative milks and the economic and cultural factors that are causing this trend is fascinating, and pairs well with the recent episode of Top Four where they (humorously) rank different kinds of “milks.”

If there’s any artist whose work was made to be portrayed on a stamp, Ellsworth Kelly would be that artist. I wish we had these new stamps in Canada, too.

A humorous piece that actually made me wince because it hits close to home: Things I Have Mistaken For Forward Momentum In My Personal Life Between The Years 1998-Present.

Jen Sookfong Lee is posting #JensHoroscopes for the Year of the Pig, and the one that she just shared for those of us who were born in the Year of the Dog resonates so strongly with me that I actually cried.

I am absolutely in love with this book cover design by Grace Han—really, almost everything Grace Han does is brilliant—but I am even more fascinated by how online shopping and photo sharing has changed the way book covers are designed.

Let your weekend ahead be marked by periods of slowness and bursts of speed, my friends. We’ll talk again soon.