A moral imperative

When we moved to the United States, and after that, to Canada, we came almost empty-handed. We had left our home in East Africa with whatever we could fit into our suitcases, and we set up a new life in North America that was, at first, meagre and austere.

I didn’t realize it then, but my parents fought hard to make sure that our basic needs were met. When they said no to my requests—new shoes, new toys, new clothes, new things that all the other kids had—they weren’t saying it out of malice, but because their focus was on paying the rent and making sure we had enough food to eat.

We were lucky to have a community, religious and cultural, that supported us in the hard times; we didn’t live a lavish life, but I never felt like I needed to go hungry. There was always someone there to feed me and look after me when my parents had to work. We were blessed to be cared for by people who had more—but not much more—than we had.

Our life these days is very different: we not only have our basic needs easily met, but we have the ability to travel, to splurge from time to time, to even buy our own home. I think of those leaner days often, though, and remind myself that there’s so much I can do, right now, to help those who still live through those days, even today.

There has been a lot of discussion about basic income and social assistance recently. A lot of that discussion has been about the economic and social impact of assistance, and why we’re rationally better to continue to help people meet their basic needs. What I don’t hear often in the discussion is the moral imperative to help others: the understanding that taking care of the people around us is the right and only thing we must do, and that it is at the core of who we are and how we must act as humans in this world.

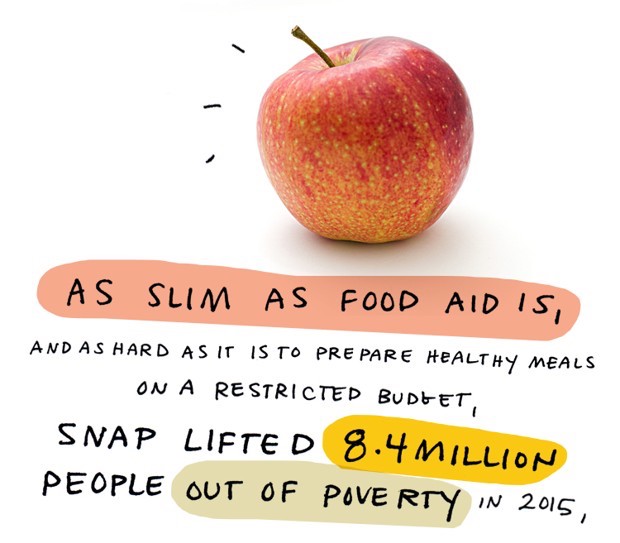

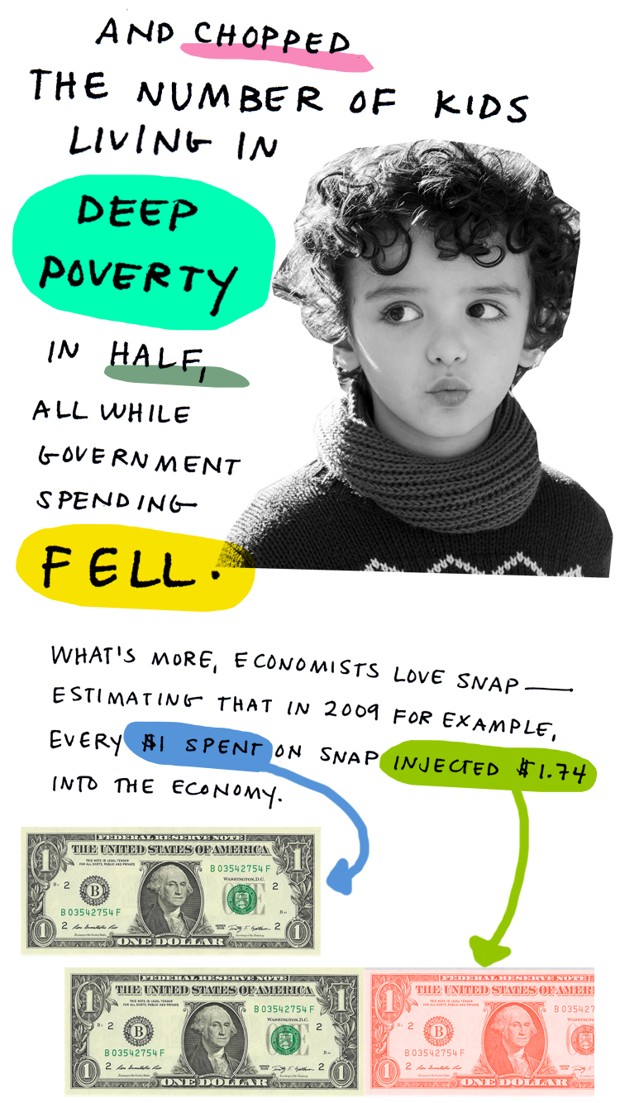

I’m reminded of this moral imperative, along with the social and economic repercussions of it, when I read stories about how people thrive and grow when they are well supported. This visual story on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program—and the threat it faces in the current administration—reminds me that there is so much more we have left to do.

The amazing people at Code for America did some great work on making SNAP more accessible for people in California. Their inspiration was a big part of why I was enthusiastic to work on supporting the creation of Code for Canada last year, and continue to be a fan and supporter.

This is, after all, what I feel we should all be doing: making life better for those around us, and to pay forward to grace we have received in our own journey through life.

It breaks my heart to know that there are people out there who do not have access to housing, food, and other basic needs. I’m lucky that we had people in our community take care of us when we were at our lowest, so it’s only right for me, for all of us, to take care of others when we can.

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT:

I wrote two pieces of marginalia over the past fortnight: a reflection on Mr. Rogers after spending the evening bawling and watching the documentary, and a quick rumination on maps after reading The Map of Salt and Stars.

A FEW THINGS TO READ AND EXPLORE:

As I mentioned above, I was in tears watching the Fred Rogers documentary, and scribbled down a few tears thoughts minutes after watching the film, but this nuanced look at Mr. Rogers’ life and lessons in our current cultural and political climate is the review everyone should read.

This is the little boy we know. This blond boy with the big plastic sword. Writer Tom Junod, profiling Rogers for Esquire in 1998, watches the host, in the midst of taping his program, approach this boy, kneel down in front of him, and say, “Oh, my, that’s a big sword you have.” And the boy says, “It’s not a sword; it’s a death ray.” And Rogers whispers something in his ear, and Junod will later find out that something was, “Do you know that you’re strong on the inside, too?” Rogers knew that boys who carried plastic swords wanted to show people that they were strong on the outside. One wonders what he would have said to Alek Minassian. “If we can encourage boys and girls to be reflective, to be introspective, then we’re avoiding pent up frustrations, we’re avoiding pent up anger because we’re able to talk through those emotions within a supportive context,” says masculinities expert Michael Kehler. That Fred Rogers was a man encouraging men and boys (as well as women and girls) to express their feelings was revolutionary. Alongside the men’s liberation movement of the seventies, which exposed the manacles of conventional masculinity, he helped to redefine the male role model. “He was opening up a conversation about being able to talk about your feelings and not feeling any less than a man because you have feelings,” says Kehler, “So he was making the invisible visible.”

The history, and current state, of indigenous people in Canada is something I’ve been ignorant of for years. I’m working on rectifying that, and doing reading and taking classes, but there’s so much more I need to do. This story of the indigenous experience and borders is beautifully striking.

For First Nations people, we have yet to come out on the other side. We are not here, nor there. Where we fit into modern society remains undefined. Today, geography is no longer allowed to be fluid. Some of us live traditionally on our secluded reservations. Some of us have fought our way to big cities, or other countries, finding new ways to connect with our culture. Should we have to choose? It’s as though we are stuck in an endless waiting room; we are waiting for someone to call our name so we can move forward, but the only ones calling our name are ourselves.

The way we move around our cities is changing—and needs to continue to change to create thriving communities—but very few cities (including my own) are engaging in conversations about completely reconfiguring our streets and our urban design.

Whether the vehicle is docked, locked, electric, pedaled, shared, or owned, there is clearly a growing group of Americans who want to use their streets in a new way, right now. Cities have spent years chastising Uber and Lyft for increasing congestion. Now these companies are proposing solutions to get their users out of cars—and cities need to work quickly on the necessary changes to make this new urban geometry work.

“Most grammar myths trace back to some overzealous language prescriptivist stating opinion as fact, often in the pages of misguided textbooks.”

We’ve got a municipal election coming up in three months, so this is a very timely, and excellent list of ten questions to ask someone running for local office.

As a fan of both sherry and scotch, this article speaks to my interests.

I use to bemoan my email inbox, but in the wake of an era of multiple inboxes (Slack, Twitter, Micro.Blog, Things, Messages, etc.) I’m slowly coming back around to the idea that email was the ultimate communication protocol.

In today’s edition of wanderlust, here are some gorgeous photos of libraries by Thibaud Poirier and a stunning collection of photos of pedestrian bridges in The Guardian.

And now, to kickstart an unending debate: the 100 best TV episodes of the century. Let the arguments begin.