Resulting: why good decisions can have bad outcomes

Hi there, it's Adam from Untools,

When you make a decision and it doesn’t have the outcome you wanted, it’s easy to look back and think “Of course I should’ve made the other choice”. But that’s a trap called “resulting”.

Today we’ll look at how a cognitive bias makes us feel bad about good decisions and I'll share two frameworks from Vault's latest deep dive on decision-making under uncertainty. The full premium post covers 5 frameworks plus a selection guide.

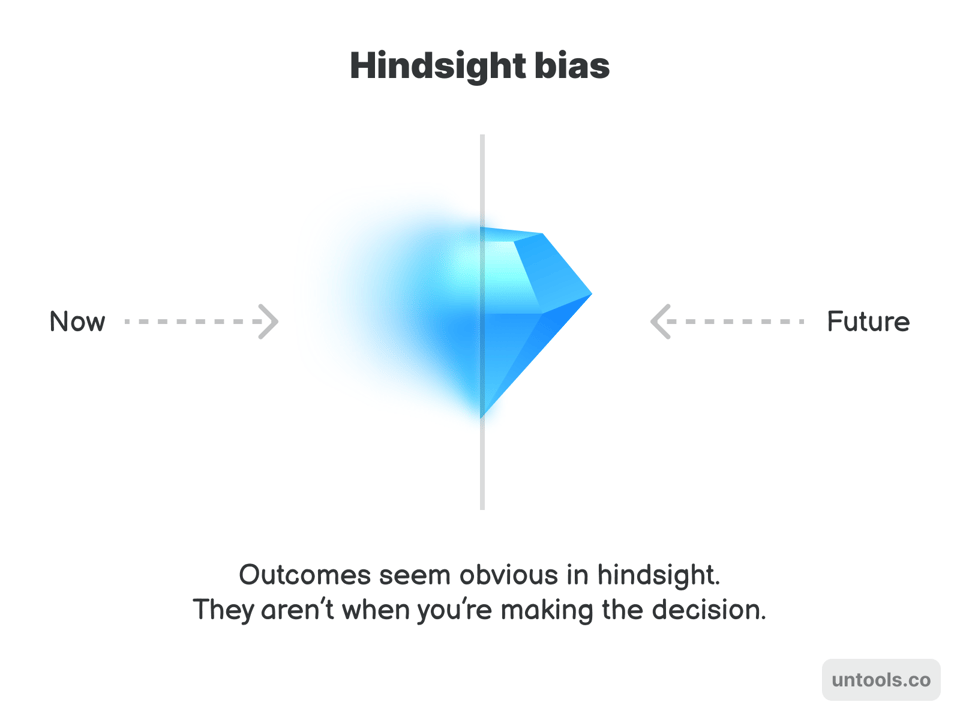

Resulting and Hindsight bias

Resulting is what happens when we evaluate decisions by their outcomes instead of the quality of thinking that went into them. It sounds counter-intuitive but a good decision can have a bad outcome and vice versa.

This is what resulting looks like: You make a decision based on the limited information you have. Later, things don’t work out. Now you know more than you did before. You look back and the “right” choice seems obvious but it wasn’t back then. You didn’t have the information you have now.

It’s a prime example of hindsight bias. Our brains assume we should’ve known what we know now and decide differently. It makes us feel bad about past decisions that were actually sound at a time.

Example: A startup CTO chooses React Native for their mobile app to ship faster with a small team. A year later, they hit performance issues and need to rebuild natively. Looking back, the native approach seems "obviously better", but at the time and with limited resources, the original decision was good despite the challenging outcome.

Deciding with incomplete information

The thing is that we will rarely have all the information we need when making decisions. Especially those big, important ones. We can’t get caught in the analysis paralysis and fear making decisions that might have bad outcomes.

The frameworks below will help you move forward even when there’s a lot of uncertainty. Some help you decide fast when appropriate. Others help when you’re really stuck and have little to no data to go on.

Frameworks for decision-making under uncertainty

One-way vs. Two-way door decisions

Every decision we make has a degree of reversibility. Some are easy to undo if they don’t work out. Others are almost impossible to reverse. The problem for making people is treating reversible decisions like irreversible ones. It means applying slow, deliberate process when a fast decision would be better.

One-way door decisions

Decisions that are hard to undo or can’t be undone at all. These are typically big decisions with serious consequences:

Choosing a core technology for your product

Selling a company

Quitting a job to pursue a new opportunity

These decisions take time and should because you need to have enough information to decide with high certainty.

Note that some decisions feel irreversible but actually aren't. Career pivots, for example, often feel like one-way doors but you can often go back or pivot further if needed.

Two-way door decisions

Easily reversible decisions. Typically things you can experiment with and change quickly.

Trying a new marketing channel

Launching a new product feature

Choosing a project management tool

The key is making these decisions quickly. The cost of being wrong is typically low so speed matters more than perfection.

Most decisions are actually two-way door but people treat them as one-way and that slows things down.

How to apply it

When you’re facing a decision, ask yourself:

Can I reverse this if it doesn’t work?

What’s the cost of being wrong?

How much would it cost (time, money) to undo this?

If it’s reversible and low cost to undo → decide quickly even with incomplete information.

If it’s irreversible or high cost to undo → take your time to gather all the data you need.

Regret minimisation framework

Some decisions are hard because they’re scary and carry big impact on our life. These are typically big life decisions like moving countries or starting a business. At the same time, we most often regret things we don’t do.

Jeff Bezos was making such decisions when he was considering to start what would later become Amazon. His way of thinking was to minimise the regret he’d later have in life and out of that came the regret minimisation framework.

How to apply it

Project yourself to the age of 80 and look back at this decision. Ask yourself: “Which choice will I regret the least?”

Imagine different scenarios and outcomes. Think about how you would feel about each. You can also use the Second-order thinking to map the possible impacts and risks.

If the answer is “I’ll regret not trying”, that’s often a strong signal to take the leap (but still plan for the risks).

When to use it

This framework is most applicable to big life and career decisions with high uncertainty:

Leaving a stable job to start a business

Moving to a new country

Pivoting your career to a different industry

Of course, think seriously about the potential impacts and risks of such decision, especially when it affects other people such as your family.

Why it works

Research shows that when people look back at their lives, they most often regret not doing something rather than things they tried but didn’t work out. This framework helps you looks past the immediate impact and consider how you’ll feel about (not) doing this much later in life…

Read the full post in Untools Vault including:

5 frameworks for decision-making under uncertainty

Guide for choosing the right framework

PDF reference cards you can print out

Vault also gives you access to 8 premium guides and deep dives (+ new post every month) and 15 thinking tools templates in PDF, Miro and Notion.

Have a great week,

Adam

P.S. If you found these frameworks helpful, I'd appreciate if you shared this with someone who might benefit from better decision-making tools.

Add a comment: