Robin Hyde and Ōrākei

Recent controversy over the destruction of Penman House in Auckland reminded me of a series of brilliant articles that Robin Hyde wrote from that very place back in the 1930s. Penman House was built in 1908 and later formed part of the Auckland Mental Hospital in Mt Albert. Hyde (the writing name of Iris Wilkinson) was a voluntary in-patient and lived in Penman House between 1933 and 1937.

During this time she wrote some of her finest works, publishing poetry, several novels and a non-fiction book. But between 1935 and 1937 she also wrote a series of brilliant articles for the New Zealand Observer newspaper documenting efforts to evict Ngāti Whātua from their last remaining lands in Auckland.

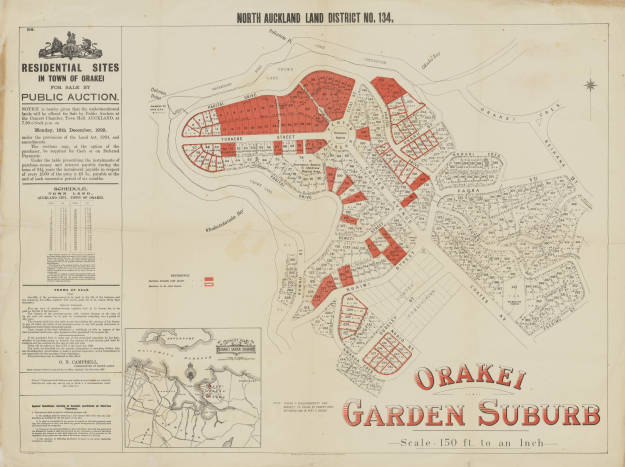

In 1868 members of Ngāti Whātua had been awarded the 700-acre Ōrākei block. But legal chicanery, public works takings and a series of underhand dealings had seen most of this pass out of their ownership by the 1920s. Auckland City Council and the government instead agreed plans for a model garden suburb, and discussion turned to how to remove Ngāti Whātua from the few acres they continued to occupy.

In 1930 a Native Land Court inquiry found that the Ōrākei block had been wrongly alienated and should have been protected as a tribal reserve. That inquiry was conducted by Judge Frank Acheson, a remarkable man who made a name for himself for what his biographers describe as a strongly pro-Māori stance that now makes him look like ‘a man ahead of his time’. Acheson stood unsuccessfully for the National Party in the 1943 election. He’d probably find no room for his views in the current party.

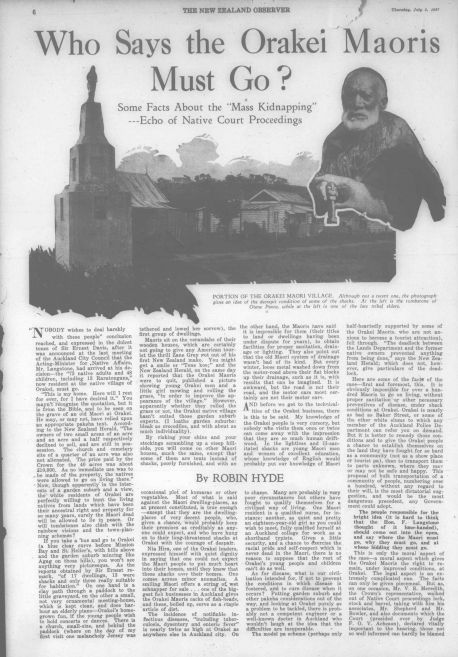

Anyway, Acheson’s judgment was reversed by the Chief Judge of the Native Land Court in 1932 and never published. Hyde managed to get hold of a copy and quoted from it extensively in the following 1937 article.

The article begins by noting the recent decision by the government to proceed with the eviction of Ngāti Whātua from their lands. John A. Lee, Parliamentary Under Secretary for Housing in the first Labour government, was a key player in this outcome. Lee and Hyde were regular correspondents and she wrote to him at one point that she was ‘very definitely on the other side of the fence’ when it came to Ōrākei and (presciently) that any unjustified removal of Ngāti Whātua from their lands ‘will never be forgiven and never be forgotten’. For his part, Lee wrote dismissively that Hyde was ‘Concerned almost pathologically with the plight of the Maoris’.[1]

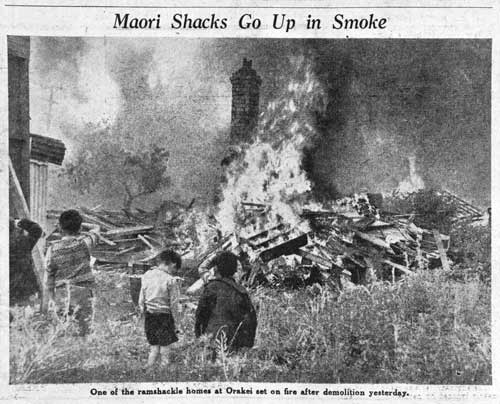

But as Hyde notes in her piece below, Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage was then overseas, and the last remaining hope rested on him overturning the decision. Savage, on his return to New Zealand, did exactly that. As it turned out, this merely postponed the eviction. In 1952 Ngāti Whātua were forced off the lands and their ‘unsightly Orakei shacks’ torched, removing a potential eyesore on Queen Elizabeth II’s planned royal route during her first tour of New Zealand later that year.

The Waitangi Tribunal quoted from Hyde’s reporting extensively in its 1987 Orakei Report that led to a Treaty settlement and the return of some of the lands.

Some of Hyde’s Ōrākei articles have appeared in various anthologies over the years. But Papers Past currently stops at 1920 for the Observer so they are not online. I copied two of her best-known reports from microfilm and reproduce the first of these below. I’ll publish the second a little later on. I think it is fair to say they remain classic and compelling pieces of investigative journalism. Like Acheson, Hyde also emerges from this sad history as someone ahead of her time.

‘Who Says the Orakei Maoris Must Go?’, New Zealand Observer, 8 July 1937

“NOBODY wishes to deal harshly with these people” conclusion reached, and expressed in the dulcet tones of Sir Ernest Davis, after it was announced at the last meeting of the Auckland City Council that the Acting-Minister for Native Affairs, Mr. Langstone, had arrived at his decision—the "73 native adults and 48 children, including 13 Raratongans,” now resident at the native village of Orakei, must go.

"This is my home. Here will I rest for ever, for I have desired it.” You mayn’t recognise the quotation, but it is from the Bible, and to be seen on the grave of an old Maori at Orakei.He may, or may not, have relied upon an appropriate pakeha text. According to the New Zealand Herald, “The owners of two small areas of an acre and an acre and a half respectively declined to sell, and are still in possession. The church and cemetery site of a quarter of an acre was also not alienated. The price paid by the Crown for the 40 acres was about £10,000. As no immediate use was to *be made of the property, the natives were allowed to go on living there.” Now, though apparently in the interests of a garden suburb and a view, the white residents of Orakei are perfectly willing to hunt the living natives from lands which have been their ancestral right and property for so many years, surely the Maori dead will be allowed to lie in peace. Or will tombstones also clash with the rainbow visions and the town-planning schemes ?

If you take a ’bus and go to Orakei (a blue clear curve before Mission Bay and St. Helier’s, with hills above and the garden suburb mincing like Agag on those hills), you won’t see anything very picturesque. As the reports obtained by Sir Ernest remark, “of 17 dwellings, 13 were shacks and only three really suitable for habitation.” On one hand is a clay path through a paddock to the little graveyard, on the other a small, not very ornamental meeting-house, which is kept clean, and does harbour an elderly piano—Orakei’s home grown fun, if the young people wish to hold concerts or dances. There is a church, small-size, and behind the paddock (where on the day of my first visit one melancholy Jersey was tethered and lowed her sorrow), the first group of dwellings.

Maoris sit on the verandahs of their wooden houses, which are certainly not going to give any American tourist the thrill Zane Grey got out of his first New Zealand mako. You might get a smile or "Tene koe;” and the New Zealand Herald, on the same day it reported that the Orakei Maoris were to quit, published a picture showing young Orakei men and a little girl mowing and rolling the grass, “ in order to improve the appearance of the village.’’ However, apparently whether they rolled the grass or not, the Orakei native village hasn’t suited those garden suburb experts. (I loathe garden suburbs: bleak as crocodiles, and with about as much individuality).

By risking your shins and your stockings scrambling up a steep hillside, you will come on other Maori houses, much the same, except that some of them are tents instead of shacks, poorly furnished, and with an occasional plot of kumaras or other vegetables. Most of what is said against the Maori dwelling places, as at present constituted, is true enough—except that they are the dwelling-places of very decent people, who, given a chance, would probably keep their premises as creditably as anyone could expect, and who have hung on to their long-threatened shacks at Orakei with the courage of despair.

Nia Hira, one of the Orakei leaders, expressed himself with quiet dignity in saying that one could not expect the Maori people to put much heart into their homes, until they knew that these shacks were their homes. One comes across minor anomalies. A smiling Maori offers a string of wet schnapper for sale . . . one of the biggest fish businesses in Auckland gives the Orakei Maoris sacks of fish-heads, and these, boiled up, serve as a staple article of diet.

The incidence of notifiable infectious diseases, “including tuberculosis, dysentery and enteric fever” is nearly twice as high at Orakei as anywhere else in Auckland city. On the other hand, the Maoris have said it is impossible for them (their titles to land or dwellings having been under dispute for years), to obtain facilities for proper sanitation, drainage or lighting. They also point out that the old Maori system of drainage wasn’t bad of its kind. But every winter, loose metal washed down from the motor-road above their flat blocks up their drainage, such as it is, with results that can be imagined. It is awkward, but the road is not their road, and the motor cars most certainly are not their motor cars.

And before we get to the technicalities of the Orakei business, there is this to be said. My knowledge of the Orakei people is very cursory, but nobody who visits them once or twice can come away with the impression that they are so much human driftwood. In the lightless and ill-sanitated shacks are young Maori men and women of excellent education, whose knowledge of English would probably put our knowledge of Maori to shame. Many are probably in very poor circumstances but others have fought to qualify themselves for a civilised way of living. One Maori resident is a qualified nurse, for instance: another, as quiet and pretty an eighteen-year-old girl as you could wish to meet, fully qualified herself at an Auckland college for work as a shorthand typist. Given a little security, and a chance to exercise the racial pride and self-respect which is never dead in the Maori, there is no reason to suppose that the rest of Orakei’s young people and children can’t do as well.

As for disease, what is our civilisation intended for, if not to prevent the conditions in which disease is fostered, and to cure disease when it occurs ? Putting garden suburb and other pakeha considerations out of the way, and looking at Orakei purely as a problem to be tackled, there is probably not a competent engineer or a well-known doctor in Auckland who wouldn’t laugh at the idea that the difficulties are insuperable.

The model pa scheme (perhaps only) half-heartedly supported by some of the Orakei Maoris, who are not anxious to become a tourist attraction), fell through. "The deadlock between the Lands Department and the former native owners prevented anything from being done,” says the Now Zealand Herald; which does not, however, give particulars of the deadlock.

Here are some of the facts of the case obviously—first and foremost, this. It is obviously impossible for over a hundred Maoris to go on living, without proper sanitation or other necessary preventives of disease, under shack conditions at Orakei. Orakei is nearly as bad as Baker Street, or some of the other white slums to which any member of the Auckland Police Department can refer you on demand. But it is better to remedy those conditions and to give the Orakei people a chance to establish themselves on the land they have fought for so hard as a community (not as a show place or tourist pa), than to transport them to parts unknown, where they may or may not be safe and happy. This proposal of bulk transportation of a community of people, numbering over a hundred, without any regard to their will, is the most dictatorial suggestion, and would be the most dangerous precedent, any Government could adopt.

The people responsible for the bright idea (it is hard to think that the Hon. F. Langstone thought of it lone-handed) should come out into the open, and say where the Maori must go, why they must go, and at whose bidding they must go.