Nelson Tenths

In December 2025 the Crown and Te Tau Ihu iwi leaders announced a settlement of a long-running legal case involving the Crown’s failure to allocate ‘Nelson Tenths’ in full. The compensation involved (the return of 7583 acres plus $420 million) far eclipsed the largest Treaty of Waitangi settlement payments ever made. But this was no Treaty settlement. The out-of-court agreement instead resolved property law litigation concerning the Crown’s breach of its fiduciary duties first heard in the High Court in 2011. Following a further series of hearings, in 2017 the Supreme Court found the Crown had a fiduciary obligation to the plaintiff to reserve the lands in question, sending the matter back to the High Court to decide the matter of defences, remedies and relief. Esteemed kaumātua Rore Pat Stafford had spent decades seeking to have the matter resolved and was the named plaintiff in what eventually came to be known as Stafford v. Attorney-General.

High Court hearings were held in Wellington between August and October 2023 and a further judgment in favour of the plaintiff the following year provided the basis for negotiations that led eventually to the December 2025 settlement. Prior to that point the Crown had appealed the latest High Court decision and a further round of hearings were expected to take place in April 2026.

In 2017 I was engaged to prepare evidence for the plaintiff, which I presented during the 2023 High Court hearing over several days on the stand.

Below I explain what the ‘Nelson Tenths’ were and set out a summary of some of the key historical evidence relating to the Crown’s failure to allocate these lands.

The New Zealand Company was founded in May 1839 to pursue the ‘systematic colonisation’ of New Zealand. As part of this scheme, the Company promised that one-tenth of the total area purchased would be set aside for the benefit of Māori. Early explanations made clear these Tenths were envisaged as inalienable endowment lands that would be managed and leased by trustees for the benefit of the principal owners. This scheme of reserves, it was argued, would more than compensate for the low prices the Company intended paying Māori for their lands. The reserves would instead constitute the real payment.

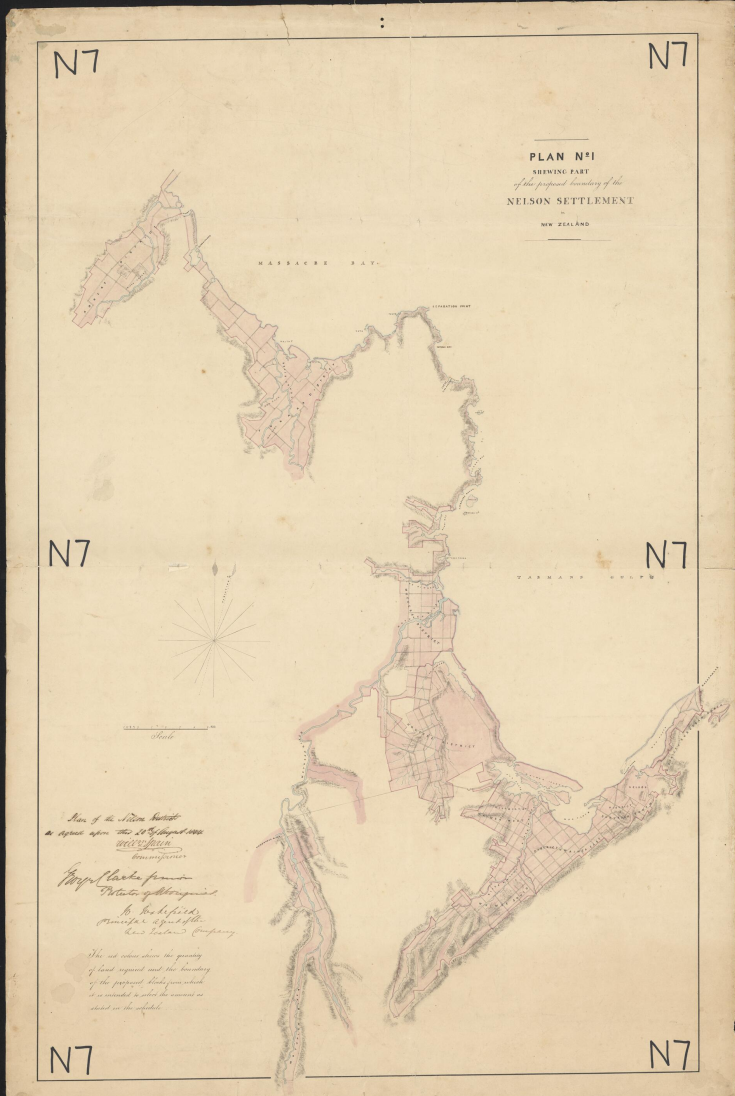

Between September and November 1839 three deeds were signed with Māori in the Cook Strait region, two of which (the Kāpiti and Queen Charlotte Sound deeds) covered an area extending from northern Taranaki down to north Canterbury. The Company made it clear in explaining the deeds that a tenth of the area purchased would be reserved for the benefit of Māori.

Following British government intervention in New Zealand in 1840 all prior land purchases were subject to a formal process of investigation by Land Claims Commissioners before grants could be awarded. However, by July 1839 the Company had already sold 990 lots in its first settlement at Port Nicholson and by January 1840 the first settlers began arriving.

In November 1840 an agreement was reached between the British government and the New Zealand Company whereby the Company would receive four acres for every £1 expended by it on the colonisation of New Zealand. Under this agreement, the Crown assumed responsibility for creating reserves for the benefit of Māori promised by the Company.

These arrangements assumed that the Company’s purchases were valid. However, when Land Claims Commissioner William Spain began investigating the Company’s Port Nicholson deed in May 1842 it soon became apparent that there were major problems with the Company’s purchase and by August it had been decided that the Company would offer Māori additional compensation in order to complete the transaction.

The charter whereby New Zealand was established as a separate colony in May 1841 made it clear that Māori rights to lands then in their actual occupation and enjoyment would be protected. That meant that such lands were not to be granted to others, such as the New Zealand Company.

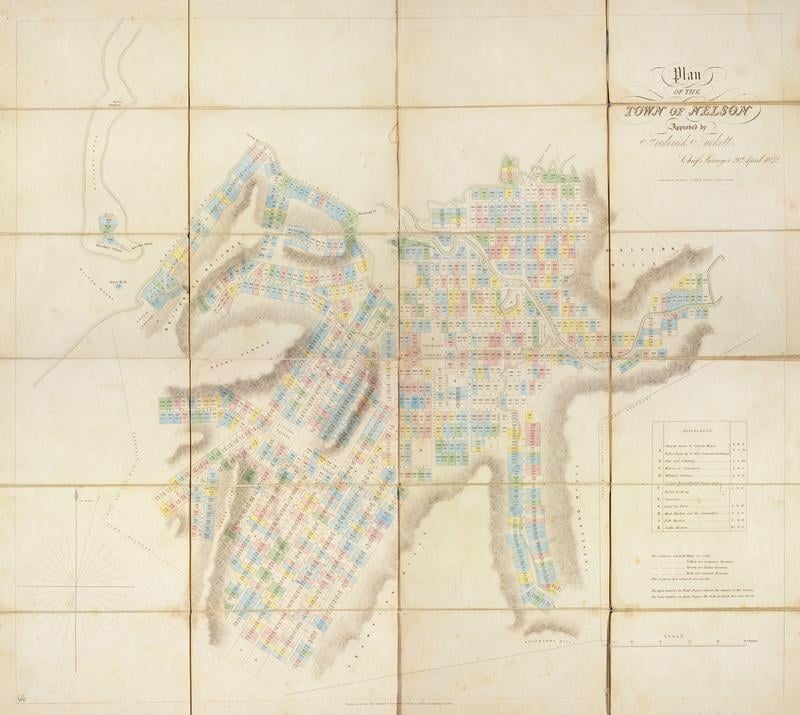

In February 1841 a prospectus was issued for a second Company settlement. Whakatū was selected as the site for this new settlement in November 1841. Resident Māori were not party to the earlier deeds signed by the Company but were given presents during the expedition to select the site of the second settlement in return for allowing Europeans to come and live among them, and promised that their cultivations would be reserved to them. There were also explanations and discussions of the Tenths scheme.

Town and suburban selections for the Nelson settlement were made in 1842. Following debate about the purposes of the Tenths reserves in the context of the Wellington settlement, in 1842 the Crown had determined that Māori pā and cultivations which had not been sold should be retained by Māori in their own possession, independent of the Tenths reserves. This decision came after the initial town and suburban selections at Nelson, where the two classes of reserves had not been clearly demarcated.

By early 1843 the Company had formed the view that it would be unable to find sufficient lands in Tasman and Golden Bays to fulfil its requirement to allocate rural lands. Attention shifted to the Wairau district but Māori there disputed the Company’s claims and a violent clash took place at Wairau in June 1843.

William Spain began his inquiries into the Company’s Nelson claim in August 1844 but the focus of proceedings quickly shifted to paying additional compensation after the only Māori witness, Te Iti, challenged the Company’s purchase. The Company agreed to pay a further £800 in compensation and deeds of release were signed soon after. In these, the signatories (in the English translations) relinquished all claims ‘excepting our pahs, cultivation, burial-places and wahi rongoa’. The 1844 deeds of release constituted further explicit acknowledgement that pā, cultivations and urupā were to be understood as excepted from, and outside, the lands purchased by the New Zealand Company.

In March 1845 Spain completed his final report on the Company’s Nelson claim, rejecting its claim to Wairau but awarding it 151,000 acres at Blind Bay and Massacre Bay, from which was to be deducted 15,100 in Tenths reserves, plus an unknown extent of pā, urupā and cultivations and any other old land claims found to be valid.

A Crown grant prepared in accordance with the Spain award was rejected by the New Zealand Company and Governor George Grey was instructed by the Colonial Office to take such measures as were necessary to provide the Company with relief.

Fewer than half of the allotments in the Nelson settlement had been sold and many of those that were had been purchased by absentee owners. From 1844 onwards various proposals were debated among owners and agents for absentee owners in Nelson regarding a remodelling of the settlement that would reflect the situation on the ground. When a remodelling scheme was finally adopted in 1847 the township Tenths were reduced from 100 to 53 acres, resulting in a net loss to the Tenths estate of 47 acres. None of the settlers had their entitlements reduced and additional Tenths were not allocated as the settlement expanded again after 1847.

In 1848 a new Crown grant was issued to the New Zealand Company that excluded all ‘pahs, burial places and Native reserves’ listed in attached schedules and plans, consisting only of some occupation reserves set aside at Golden Bay plus 5053 acres in Tenths reserves.

The Crown never allocated 10,000 acres in rural Tenths or to remedy this shortfall subsequently. It also failed to clearly demarcate pā, urupā and cultivations, which had never been sold. By 1882, when the Tenths that had been allocated were vested in the Public Trustee to administer, the Tenths estate had been reduced to approximately 2745 acres, or less than one-fifth of the original entitlement of 15,100 acres.