‘Native Districts’ and the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852

Asked to nominate the point at which relations between Māori and Pākehā had really begun to turn sour in the nineteenth century, many historians would likely nominate the passage of the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852. As Chichester Fortescue famously told the House of Commons in 1861, from the time of the 1852 Act the governor had been ‘[o]bliged to act under a Constitution which appeared to have been framed in forgetfulness of the existence of large native tribes within the dominions to which it was intended to apply’.

It is true that the implementation of the 1852 Act contributed significantly to the crisis that unfolded by the early 1860s. But it didn’t have to be that way since the new constitution also provided for self-governing Māori districts beyond the jurisdiction of the settler parliament to be formally recognised. And a similar provision had been included in an earlier 1846 constitution for the colony. That earlier measure is less well known.

Responding to calls for self-government from the relatively small body of settlers in New Zealand and their supporters in the United Kingdom, in 1846 the British Parliament passed an Act providing for a House of Representatives for each of the two provinces of New Ulster and New Munster in New Zealand, with a General Assembly above to be composed of members of both provincial chambers. Municipal corporations would also be established but under instructions issued in tandem with the new constitution, voting would be restricted to adult males able to read and write in English.

Māori had relatively high literacy levels at this time, but overwhelmingly in te reo Māori rather than English. The effect of this measure would therefore have been to disenfranchise the bulk of the majority Māori population. Governor George Grey warned that there was no reason to expect that Māori would be satisfied with or submit to rule by the minority, informing the British Secretary of State for the Colonies that:

the race which is in the majority is much the more powerful of the two; the people belonging to it are well armed, proud, and independent; and there is no reason that I am acquainted with to think that they would be satisfied with and submit to the rule of the minority, while there are many reasons to believe that they will resist it to the utmost.[1]

In 1848 Grey managed to get this provision postponed for five years. That left the question of what part Māori would play in any future parliaments in limbo. At issue was how the demands of a growing settler population for self-government could be reconciled with the need to placate a still dominant Māori society. It was clear to Grey and others that any attempt to impose settler government on Māori would be resisted. But other alternatives were also available.

In 1852 the New Zealand Constitution Act was passed by the British Parliament, replacing the 1846 measure. It replaced the literacy test with a property qualification in order for adult men to be eligible to vote. While in theory that should have been no difficulty for most Māori men at this point in time, the problem was that their lands were still overwhelmingly held under customary or native title and the law made no allowance for this fact.

In effect, the new Act continued to pass power to the minority settler population while excluding most Māori men from the franchise. Encouraged by Governor George Grey’s numerous reports of Māori progress towards ‘civilisation’, many British parliamentarians wrongly assumed that significant numbers of Māori would be able to vote under the new constitution.

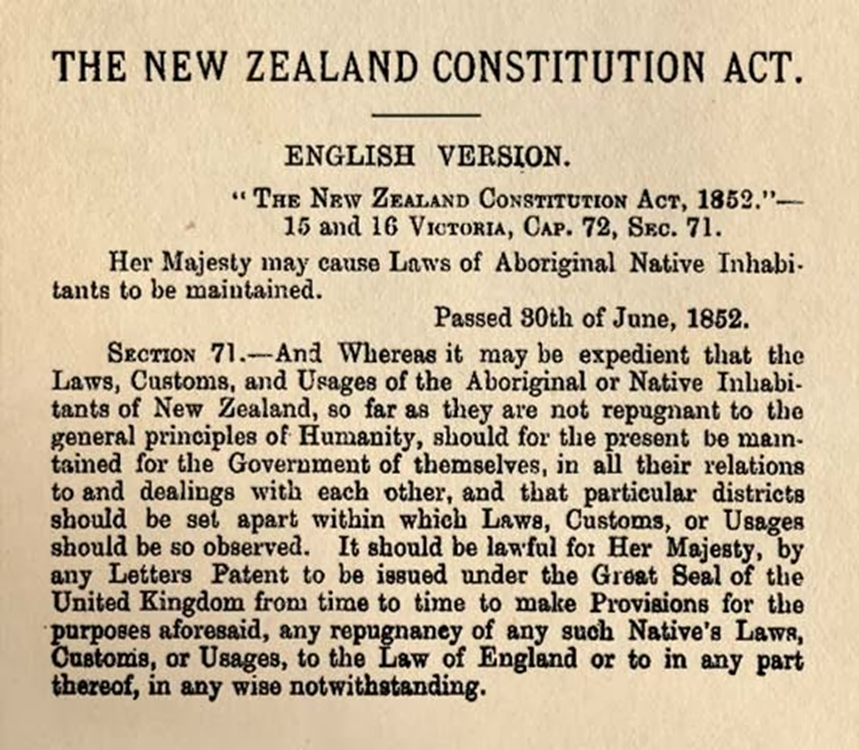

For those who could not, section 71 provided a further safeguard, at least until such time as the Māori communities in question were able to participate in elections. It provided for ‘native districts’ to be declared in which Māori customs, laws and usages would prevail so long as they were ‘not repugnant to the general principles of Humanity’. British parliamentarians assumed that such areas would not be subject to the jurisdiction of the General Assembly to be established but instead would effectively be self-governing, under the overarching authority of the Crown. That would have provided de jure recognition to the de facto situation that then prevailed in many regions across the colony, where tikanga prevailed as effectively the only operative law.

A similar measure had been introduced in 1846, with the British Secretary of State for the Colonies envisaging that the jurisdiction of the provinces would initially extend only over European settlements. Earl Grey made it clear that in making such a provision he was following the general principles governing relations with Māori set out by Lord John Russell as Secretary of State for the Colonies. In December 1840 Russell had informed Lieutanant-Governor William Hobson that, while certain presumed customs such as ‘cannibalism, human sacrifice, and infanticide’ could not be tolerated under any circumstances, other customs deemed not objectionable might be made the subject of ‘some positive declaratory law, authorizing the executive to tolerate’ their continuing usage.[2]

Section 10 of the New Zealand Constitution Act of 1846 enabled districts to be proclaimed in which the customs, laws and usages of ‘the aboriginal or native inhabitants of New Zealand’ should, so far as they were not ‘repugnant to the general principles of humanity…be maintained for the government of themselves in all their relations to and dealings with each other’. Instructions accompanying a new charter for the colony in December 1846 provided for ‘Aboriginal Districts’ to be declared in which ‘the laws, customs, and usages of the aboriginal inhabitants, so far as they are not repugnant to the general principles of humanity, shall for the present be maintained’.[3]