How HBCUs Can End African American Underrepresentation in Science

A Q&A with Dr. Joseph Graves, Jr., on the effort to make historically Black colleges and universities “wither on the vine.”

(Read to the end for Juneteenth-themed speculative fiction reviews by Kristen Koopman and a discussion about the “best” disaster movies.)

It’s a weird time to be writing about power structures in science, something I’ve spent much of my journalism career focused on. For years, I have been highlighting how science workplaces need to change, but now find myself reporting on how we need science workplaces, flaws and all. These two issues—attacks on science and justice issues in research workplaces—are profoundly related in complicated ways. The story of scientists at HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges & Universities) demonstrates that relationship, and also demonstrates why these institutions are especially vulnerable right now.

In November 2024, just after the election, I saw evolutionary biologist Joseph L. Graves, Jr., give an impassioned lecture to the National Association of Science Writers on the role of HBCUs in science. I was excited to attend his talk, because I have been grappling with the question: How does one work toward justice-oriented research within patriarchal, white supremacist institutional structures? I knew that research at HBCUs would help me consider this question.

Dr. Graves, the first Black man to hold a PhD in evolutionary biology, has spent his career living this question. I asked Dr. Graves that question after his talk, and he said that he talks about power with his mentees regularly. He is the MacKenzie Scott Endowed Professor of Biology at North Carolina A&T State University. I highly recommend his autobiography, A Voice in the Wilderness. In December, Dr. Graves sat down with me for an interview about the history of HBCUs and justice-oriented science. Here’s an excerpt from our conversation, lightly edited for flow and clarity.

A note: This discussion is about racial trauma. I am eternally grateful that Dr. Graves sat down with a white person like me and was so candid. For white people, many of us have been socialized to be defensive and angry when confronting America’s disturbing racial history. For African Americans and other nonwhite people, these topics may raise memories about their own traumas. Take some deep breaths, take a break if you need, go touch grass or text a friend—but please read to the end. There is great joy and community to be found when we shine light on our shadows. And there’s fun stuff, too, like Star Trek and, you know, a better world. Here we go.

How did HBCUs form, and what is the policy landscape behind the funding disparity compared with historically white institutions?

Historically, Black institutions were formed as part of both the colonial enterprise of the United States, as well as the resistance to that enterprise.

During slavery there were very few persons of African descent who could attend higher education. My alma mater, Oberlin College, was the first nonblack institution to admit African Americans to study there, and that was in 1835. (In 1833, Oberlin had been founded as the first coeducational college, but it took two years of debate to open its doors to persons of African descent.) Oberlin played a big role in the Abolition movement. But there were very few African Americans who could attend colleges or universities and receive degrees.

After slavery was ended, a number of Black colleges were founded to educate the newly freed people. Howard University in Washington, DC, was one of them. Howard received federal funding.

At the same time, Congress passed the 1862 Morrill Land Grant Act to provide higher education opportunities for a larger sector of the American people, founding most of the major state research universities that you know of today.

In the former Confederate States, persons of African descent could not attend those institutions. So, 30 years later, a second Morrill Land Grant Act was passed, the Morrill Land Grant Act of 1890. This established 19 colleges and universities for persons of African descent in the former Confederate States.

Now, what they meant by higher education at the time was for women to receive training to become seamstresses and domestics, and for men to learn how to be better farmers. So, these were not universities in the modern sense at all, nor were they commensurate in training with the white universities of the time period, nor were they funded like those white institutions.

Shortly after the passage of the second Morrill Land Grant Act was Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court decision that made “separate but equal” facilities legal throughout the United States, so long as those facilities were funded equally. Now that never happened in education, neither in K-12 schools nor at the university level in the former Confederate States. Even worse, these states pilfered money from Black education to pay for white education, double dipping and further underfunding Black education to the present day. This is well-documented in Adam Harris's book The State Must Provide, in which he does this masterful, scholarly treatment of this pattern of underfunding and robbing Peter to pay Paul (where Paul was white education, and Peter was Black education).

My own institution, North Carolina A&T, which is one of the most powerful and the largest historically Black state institutions, based upon calculations by the Biden Administration two years ago, is owed over $2 billion since the 1930s by the State of North Carolina. And this is a pattern that we've seen all over the country. Morgan State won a major settlement against the State of Maryland recently, and they received about $500 million of what they'd been owed. But Morgan is the counterexample. The vast majority of the historically Black institutions formed in 1890 have never been given full restitution for what they're owed, and are still consistently underfunded relative to their student population and needs.

If you had that $2 billion, how would science and higher education be different?

If that money was given to us today, we could change the demography of many disciplines in science within a decade. That's really what's holding us back.

The people who currently make up the workforce within the enterprise of science are going to be solving the problems that they think are of great significance to their community. Now, many of these people don't recognize that they're engaging in implicit bias in the questions they choose to investigate and how they choose to investigate them. It's normal. A fish does not know it's wet. As our society becomes more stratified by class and race, that is exactly what happens to these people: They have no idea what it's like to not be in their community. Then, they're going to do the science of interest to them and that seems beneficial to their community.

If we had the funds we were owed, we would be able to train more African American medical doctors, more African American dentists, more African American scientists, more African American business professionals, and so on. We would be able to have people with the credentials to get into these industries and these professions, and be in the room when decisions are being made. And I guarantee you that would give us a different enterprise.

But the folks who currently dominate that enterprise have no real investment in making that change. It's not that all of them are racist. But there are enough racists, sexists, and anti-gay bigots in these enterprises who, with the passive agreement of the majority of people who claim that they are not political, can steer the way things go. They were able, for example, to eliminate affirmative action a few years ago.

How does chronic underfunding affect your institution?

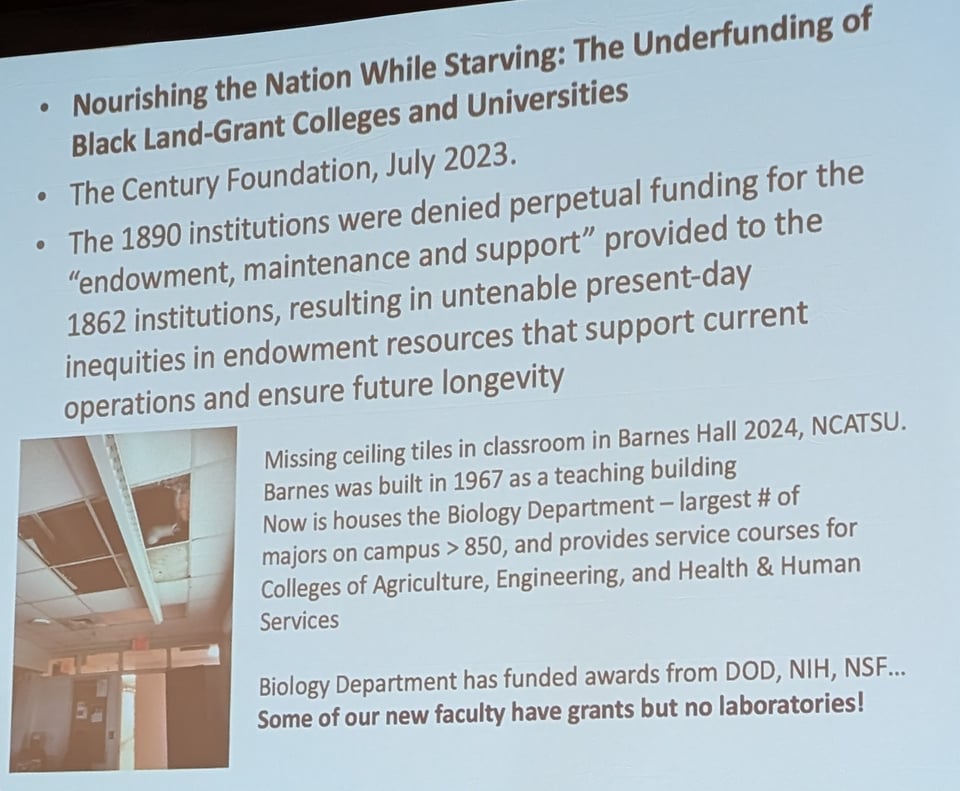

We're always in a position of having to pull funds that should be supporting things like a division of research to run things like the power plant.

Last winter, we had to send students home because the power plant crashed and there was no heat in the dorms. This morning, my TA was over here helping me grade exams. She had a coat on, because the central heating plant is never working properly in the biology building, which was built in the 1960s.

In the summertime, we couldn't run our sequencer because the temperatures in the building were so high that the sequencer wouldn't function. So how are we supposed to keep our research at the same level as our colleagues who have brand new biological sciences buildings? Not to mention the fact that we have to teach more classes, advise more students–and these students come from the worst school districts in the nation?

I've taught classes at NC State; I teach classes at Duke. Give those students an assignment, and they'll be fine. I have students who can't do 8th-grade algebra. I have to teach them that before I can teach them the material in evolutionary biology. These injustices are so clear, so apparent. And this country continues to look the other way as if this is fine, and of course create an entire edifice of scientistic sounding theory about the genetic inferiority of people of African descent. That's what we're up against: A nation that believes this.

How did you become interested in science?

There was no one in my family who was a professional in any kind of science or medicine. So I got interested in science from watching television, particularly the original series of Star Trek, which had a multiethnic cast and allowed a child around 10 or 11 years old to think about the possibility of being on a spacecraft and making great discoveries.

When I was in third grade, the teachers assumed that I was intellectually inferior. They assumed that of all the African American kids in the classroom. They wanted to put me in special education. They didn't realize that the work was so simple to me that I became a “behavior problem.” I was a young boy with nothing to do. So it actually took a young lady who was a student teacher who didn't know me and had come in to teach classes at the elementary school and who saw me reading a very large, graduate-level book in history in the library. All the other teachers had assumed that I opened these big books because I didn't know how to read, and I was just showing off. This teacher sat down and asked me about what I was reading. And when I gave her a quick synopsis of the First, Second, and Third Crusades, she realized I was different. The next day, I was transferred into the advanced learning groups.

In high school, I was the only African American in my classes–in math, chemistry, physics, biology. I went to Westfield High School in Westfield, NJ, which is a bedroom community for New York City. The parents of most of the kids in my classes were Wall Street and Madison Avenue executives, doctors, lawyers–they were extremely wealthy. And so we had great science instruction in that school.

Then, I went to Oberlin College as an undergraduate. I went there because they had the only brochure that had pictures of people who looked like me. This would have been 1972 or 1973.

Oberlin produced more PhDs per capita than any other liberal arts college in the nation. It was a completely new society. I had no idea how smart the kids at Oberlin were when I got there, from families that had gone to college for generations. Because I wasn't part of that culture, I struggled. I barely had a 2.7 grade point average overall when I graduated, and so I wasn't recruited by the top graduate programs.

How did your path in science intersect with racial justice issues after college?

I decided to accept an offer for a TA-ship at the University of Lowell at the Institute for Tropical Disease–now you would know that school as University of Massachusetts Lowell. The African American students there were clearly an oppressed minority. Most of them walked around the campus with their heads down, being told consistently that they're only there because of an affirmative action program and that they weren't smart enough to be there. I was called “n*****” on that campus more times than I can count.

I had to make sure that people understood that I was not there because of affirmative action. Because I did so well at Lowell, I applied for the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, and again, not knowing much about graduate school, I only applied to two programs: Harvard and Michigan.

My interest in Harvard was specifically to work with Richard Lewontin. If you know anything about the history of population genetics in the 20th century, Richard Lewontin was one of the most brilliant minds. He was also a Marxist. I had many conversations with him, and he was interested in me coming to Harvard to work with him. I had met him through Stephen Jay Gould, who I had met when he was giving a seminar at the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole when I was there for a summer program.

I am the only person in the history of the Graduate Research Fellowship Program to be rejected by a university. The Graduate Research Fellowship program is the most prestigious graduate fellowship the National Science Foundation gives; it pays for the student’s tuition and stipend. The university that accepts them doesn't pay a dime. Why would any university turn down a person bringing a graduate research fellowship?

Well, the letter I got from Harvard said this: “Dear Mr. Graves, We find that your qualifications are entirely consistent with attending Harvard University. However, we cannot find a faculty member who is willing to take you on as a PhD student. Therefore, we are declining your admission.” This was after Dick Lewontin had told me that he would be happy to have me as a PhD Student. Turns out, the day the graduate committee met, Lewontin wasn't there. They didn't like him at Harvard anyway–you know, E. O. Wilson was there at the same time.

Turns out, it was the best thing that ever happened to me, because Michigan was really happy to have me. I worked with Jack Burch in the mollusk department, who was a great guy. But he just wasn't the right person for me at the time. I ended up hanging out with John Vandermeer, who was one of the founders of mathematical ecology, and he was also a radical. John was the person who taught me that biology is a social weapon. I give him a great deal of credit for helping me become the scientist that I eventually became.

Of course, when I got to Michigan, I was one of very few Black students there. I got involved in student activism to change the institution, particularly around the fact that there were a whole bunch of Black athletes on the campus, but very few Black undergraduate students and even fewer Black graduate students.

That student activism cost me my time at Michigan. My grade point average dropped to 2.99, and the graduate school didn't bother to warn me, didn't attempt in any way to keep me on campus. The moment my GPA dropped to 2.99, I got a letter saying I was expelled. And I had had it with Michigan anyway. So it was one of these win-win situations where they got rid of me, and I didn't want to be there anymore.

I spent a great deal of time in Detroit doing more activism, organizing against the Klan and for workers rights. I was married by that time. My wife and I were starving to death, and I just got to the point where doing all that work with little reward and seeing the woman that I loved freezing to death without a coat, shoes, money, I decided to go back to grad school. And so that's why I went to Wayne State and ended up earning my PhD there.

Many historically white universities have been criticized for lip service to diversity, equity, and inclusion, without making meaningful changes. What have you seen work?

Some do better than others. I think the University of California, for example, through their President's Postdoctoral Fellowship Program, has done more than many of the other major state institutions. I earned the President's Postdoctoral Fellowship, which led to my becoming a faculty member at UC Irvine. And I know other people who benefited from that program. But that program is the exception to the rule.

Studies have been done on these institutions, particularly those, for example, that had created positions for chief diversity officers and so forth. There's no difference between those schools and those that didn't in terms of diversity of their faculty, graduate students, postdocs, undergraduates–no difference.

This is one of the reasons why I believe that even though there are good people on these campuses, who are devoted to this issue and recognize its importance, they are simply outnumbered.

That is why I consistently argue that what has to happen now is that funds need to be appropriated to historically Black, minority-serving institutions, so that they can build their infrastructure and be able to compete on a level playing field, because we have no ideological impediments to doing this work. We know how to do it. Our problem is, we don't have the infrastructure. We don't have the funding.

How have your experiences in science and education affected how you mentor students to confront these issues?

Well, I am honest with my students. I tell them that they don't have any friends. Once they leave this campus, they have to be academically sound at all levels. And the way we have to operate in white spaces is the 1.3 rule: If your white colleague does 10 papers that year, you gotta do 13. That's what happened to me when I was in those spaces. I always had to do more.

The majority of our STEM faculty in my department at an HBCU are not African Americans, because African Americans are so underrepresented in these fields. That is true of all HBCUs. Most of our faculty are from the underdeveloped world–from India, the Middle East, Western Africa, the Caribbean. Some European Americans work here, but most of our faculty come from those countries which were being exploited by global imperialism.

One of the things that I do as a senior faculty member is I mentor all the junior faculty that come in here, not just to help them be successful independent research scientists, but also to help them understand the student body that they're going to be working with, particularly those of European descent who don't really know what these kids are going through.

How do you think the Trump administration will affect HBCUs? [I asked this question in December 2024; Dr. Graves was remarkably prescient.]

Their plan will be essentially to let us wither on the vine. They'll find all sorts of ways to cut federal support from HBCUs and minority-serving institutions. The state legislatures will not make up the difference, and many of them will join in this movement. So, things are going to get worse. I was actually planning to retire, but after the election, I decided I can't.

As someone who started out in science and saw the problems that science has, as well as its importance to society, I wish I had been taught this hidden curriculum of how power operates in science. These issues seem so intractable right now. What have you seen work?

What works in the context of the environment I'm in is mentoring. I use a tiered mentorship approach. I mentor assistant and associate professors, postdocs, graduate students, and undergraduates. But everyone that I mentor I train to mentor those below them.

As a result, my research group has done tremendous things over the last 10 years or so, compared with other places in the country. For example, we've graduated five Black women with PhDs in microbial evolution in the last five years. That is more than the rest of the country has graduated in five decades. We do research in partnership with R1 institutions like Duke University, UNC Chapel Hill, NC State, and Yale. Everybody wants to partner with us, because at least those who still retain some allegiance to DEI all want to partner with us because we produce really good students.

We graduate more Black female engineers than any university in America. But then the side that people don't see is all the people that we can't graduate because the society has done so much to hold them back. This afternoon I'll be meeting with a woman who's trying to earn her degree while she's working a full-time job. We have many students who are in my classes who are going to fail this semester because they're working a full-time job. They can't come to class. I only see them three days during the semester: first in-class test, second in-class test, and final exam. No surprise that they fail the course. I had one student–and this guy actually did graduate–who I found sleeping in the biology auditorium because he was houseless. He thought I was going to turn him in; I got him help. But that's who we are working with–and at the same time having to write research grants to compete in the same panels as people at UNC Chapel Hill and NC State.

I feel like most scientists want a more just, equitable workplace. But workplace and institutional structures get in the way.

You know I will agree with you. But it's not going to happen by most people's desires. It's going to happen when most people understand one, that they have the collective power to make change, and two, they have the courage to step out and make the change. What I have seen over the course of my life is the spinelessness of most people.

I mean, I think that if you ask that person in an abstract conversation, “Should everybody be given equal opportunity?”, the vast majority of them will say yes. The vast majority of them will be aghast when you tell them that there's really not equal opportunity. Where they fail is the willingness to step out, to confront the source of the unequal opportunity, to be willing to make personal sacrifices, to move for justice. That is the problem.

As Dr. Graves predicted, federal cuts are disproportionately affecting HBCUs, which are already disproportionately underfunded. HBCUs especially need our support right now, as all higher education institutions are planning their next fiscal year amid financial chaos right now. I hope you’ll join me in donating to an HBCU near you or another HBCU-supporting nonprofit or foundation. You can donate to North Carolina A&T here.

Dr. Graves’s forthcoming book, Why Black People Die Sooner: What Medicine Gets Wrong About Race, and How to Fix It, is available for preorder.

Kristen’s Corner (by Kristen Koopman)

For this issue, in celebration of both the subject matter and Juneteenth this week, I have a couple of speculative fiction recommendations: a story, a magazine, and a movie. (The movie is last because you probably know what it is already.)

Algorithms tend to be used as a way of laundering bias into supposed objectivity. There are plenty of scholars doing excellent work to describe exactly what that means—Timnit Gebru and Damien Patrick Williams come to mind—but sometimes fiction is better at showing things, and this story shows the flipside of algorithmic injustice. Onyebuchi follows a fictionalized account of algorithmic justice: using an algorithm to calculate the reparations due to Black residents of a city to make up for the legacy of racism. What follows is a detailed and vivid unfolding that gets at the heart of the things that have for so long been left deliberately unseen.

Slate's Future Tense also has its stories accompanied by relevant commentary by subject matter experts, and Dr. Charlton McIlwaine's essay is not to be missed.

The Magazine: Fiyah Magazine

Fiyah is a Hugo Award-winning speculative fiction magazine with authors from the African diaspora. Speculative fiction is arguably always in a bit of an upheaval, but the industry has been under some unique pressures lately, and good work ain't cheap. You can donate or, better yet, subscribe to read all the great stories coming out of Fiyah!

The Movie: Sinners

Yeah, this is possibly the least original suggestion that can go here, but Sinners is absolutely stunning. I have to admit I'm a bit of a scaredy-cat (you're not going to see a lot of horror recommendations over here), but I prepared myself emotionally and went to the theater to see it and I'm so glad I did. It's available on streaming now, and truly there's nothing I can say about it that you probably haven't already heard. So just add my voice to the chorus saying: Watch it.

Tell Us What You Think

Please tell us here what sorts of content and subscriber perks would incentivize your subscription. In the meantime, please subscribe to the free version and buy me a coffee here.

Recent Things I Wrote:

Medical Research Funding, Unbreaking, a project tracking the impacts of federal cuts [I wrote a few things on this page; Liz Neeley led the writing.]

How scientists can reach a more bipartisan audience, AHCJ

Bird flu: Background and data overview for reporters, AHCJ, coauthored with Tara Haelle

Recent Things I Recommend:

Understood: Who Broke the Internet, by Cory Doctorow

Public health is a utopian vision (with Naseem Jamnia and Natasha O’Brown), Our Opinions Are Correct

Stay Sane: 80 Tiny Moves to Resist Digital Despair and News Overwhelm in the Trump Era, by Paul T. Shattuck

Carnivorous Plants Have Been Trapping Animals for Millions of Years. So Why Have They Never Grown Larger?, by Riley Black

Something Fun:

Ok geology pals, I need some help. In your opinion what are the “best” disaster movies? Specifically - 1) The 'best' or most scientifically interesting depiction of a disaster 2) The funniest or most ridiculous disaster movie 3) Your favorite 'guilty pleasure' disaster movie

— Dr. Wendy Bohon (@drwendyrocks.bsky.social) June 9, 2025 at 9:28 PM