Centerfold

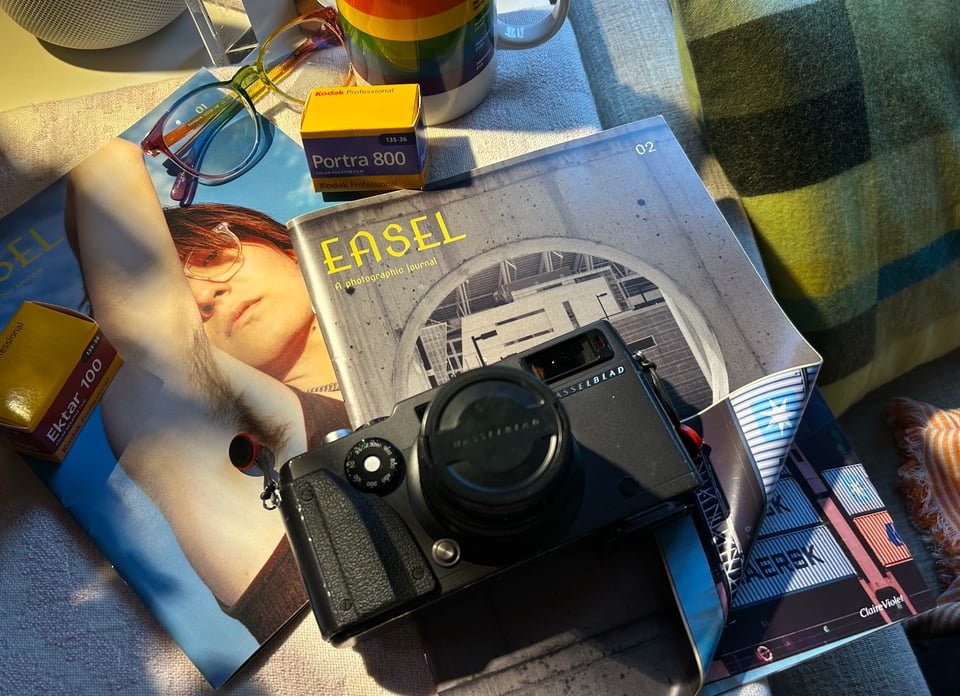

Announcing Easel 02, a transsexual photography magazine, in which my photographs have been published!

Easel 02, a photographic journal.

I’m very honored to have five of my photos published in the second edition of Easel, a “print-first photographic journal made by transsexuals.”

You can purchase a digital copy here, or a print copy while supplies last.

I purchased the first edition of Easel myself this past summer, and was blown away. The magazine was beautifully done, and the work inside was even more fantastic. It was a wonderful survey of trans photography, covering the styles and subjects I’ve seen in my own local collection of trans photographers. I knew instantly I wanted to contribute when calls went out for the next edition, and I’m very pleased to have been accepted.

I think there’s something especially important about producing physical media of trans art at this current moment. I talked about this on Bluesky recently—that myself and my friends have been creating so much photographic art in the last few years, and I’m very excited that there is some outlet for it. I’m especially excited to know there is a photo magazine with editors who are and want to highlight trans photography, who understand and share our perspectives, and who see value in publishing this in a tangible form.

Submitting to Easel back in early November, I was proud of my photographic work, but I really wasn’t sure anyone would see the value in it enough to publish it anywhere. This is the first—and so far only—place I’ve ever been published, and it being intentionally trans-focused made the potential for rejection much more approachable for me. It gave me something achievable to strive for, and helped me bring a critical eye to my own work before submitting.

Starting early this fall, I’d been printing more and more of my work. I found it really benefits—like most photography does—from being seen outside of a screen, in the more intimate environment of home. Perhaps all photos desire to move from frames on gallery walls to magazines or photobooks and be treated like prized possessions, secreted away. Panoramas especially are desperately begging to be viewed up close in your hands or at large sizes, unconstrained and reflective of the scale of the world that stood before them when they were captured. If I was going to have my photos printed, I had to submit panoramas, but which?

The call for Easel’s second edition read:

Winter isn’t far, and we’re hoping to start spending more time with less people. We encourage prospective contributors to turn their attention to seriality and cohesion.

I found myself in a very fortunate position, sitting on a large body of existing work featuring nonhuman subjects which I’d spent all spring, summer, and autumn developing.

My photos which appear in Easel 02 are some of my finest work from my ongoing series “Maritime, Manufacturing, and Logistics” where I’ve been exploring the depersonalization, beautiful bright colors, complex shapes, and large scale of industrial sites on the west coast, especially the ports of Seattle, Tacoma, and Oakland. In this issue, two of my photos from Oakland spill across two pages to form the centerfold. They show detailed views of a Maersk container ship as well as a ship-to-shore crane up-close. The afternoon light of the Bay is soft and gorgeous on these enormous steel constructions.

For a preview of what you’re getting into, here are two bonus images from the same series which I’ve shared on Bluesky, Glass, and Instagram.

I think there’s something fascinating about this world. Especially here in Seattle, so much of our city’s land use is dedicated to the harbor. Take a look on a map and you’ll see an island bigger than many of Seattle’s neighborhoods, populated only by boxes and seabirds, right in the middle of everything. So often I find myself needing to pass by it to get where I need to go and wonder: How many sunset views and quiet afternoons by the water are inaccessible because of the port? I started to take motorcycle rides to parks and observation points placed within the middle of the port, curious why they were there in the first place. Was this part of some kind of deal with the city for expanding Harbor Island? An environmental cleanup throw-away effort? Who but me was even aware these spaces were open to the public?

Some of these port parks were once an important industry that closed down which haven’t found a new purpose yet. They’ve been turned over to the public in a genuine and sincere attempt to make port work visible to anyone with an interest. They have an optimism and pride for labor and blue-collar work that I find quaint, but very moving from my modern ironic context. Many others, especially here in Seattle, presented a darker view of colonialism, environmental destruction, and attempts at restoration. These spaces simply represented the city they were a part of. I’d sit and watch everything going on as the afternoon turned to evening and ride home.

Container ships are especially beautiful to me. These enormous vessels pass right by the places we live and quietly disappear, sailing out at sea for over a month. They’re plastered with advertising, each and every container loaded onto a vessel the size of a city is itself the size of a billboard, and yet you cannot purchase their services—That’s not for you. That’s for someone else. A worker looking for a can lost in the stacks, maybe. An executive seeing a freight train passing through the middle of America, sure, but not you. Call your local harbor and naively ask for a tour, as I have, and be firmly told “no” for “reasons of national security.” You should stay away.

My photos in Easel showcase an aspect of my industrial photographs which I try to be subtle about. My centerfold photos especially are strangely intimate, even if they didn’t come with the connotation of being—quite literally—a centerfold. They’re stolen glances of a world fenced off with razor wire, that you can appreciate in detail instead of from afar, no longer kept inaccessible across the water.

I think the scale and shapes of these massive objects lends itself well to personification and metaphor. Stand behind the fence sometime and watch the graceful movements of a container ship being unloaded, as a crane operator swings a box the size of a bus hundreds of feet in the air and lands it onto a chassis it could crush without thinking twice. Alarm bells ring every time one of these towering objects moves even slightly. You’re left feeling small, standing on the ground staring at the massive legs reaching toward the sky far above you. They’re dangerous and loud, with cables and hoses dangling off them on every side, tied up. If you can’t find anything a little bit erotic in that metaphor, well, then you and I aren’t that alike.

Either way, I hope you enjoy my photographs. 💜

XOXO, ClaireViolet