Review: We Told You So: Comics As Art (2016)

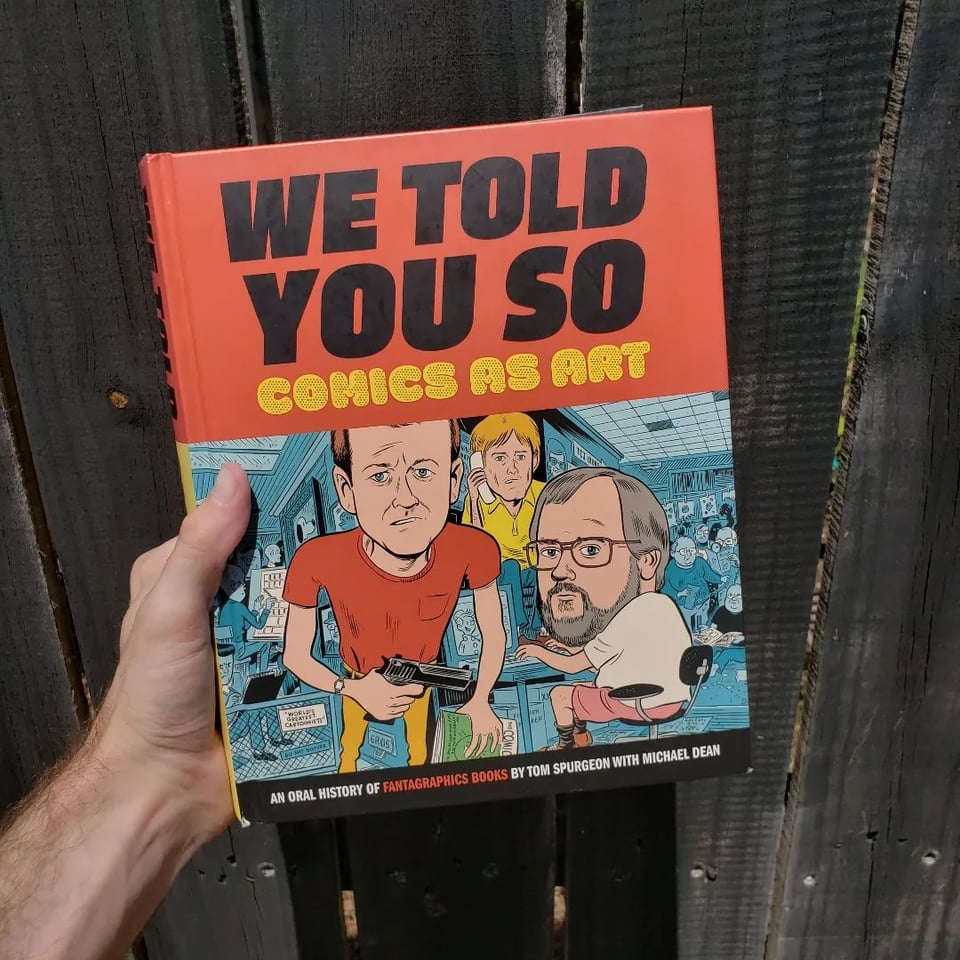

The only reasonable place to begin a review of We Told You So – a self-described “oral history" of Fantagraphics, the influential publisher of alternative comics – is to note its ungodly and frankly unreasonable heft.

This book is nearly 700 pages long and packed with interviews from dozens and dozens and dozens of people affiliated with (or formerly affiliated with) Fantagraphics: publishing staff, artists they’ve published, interns (always unpaid), hangers-on, even the parents of the company’s co-founders. The number of people quoted here represents a massive, impressive amount of work.

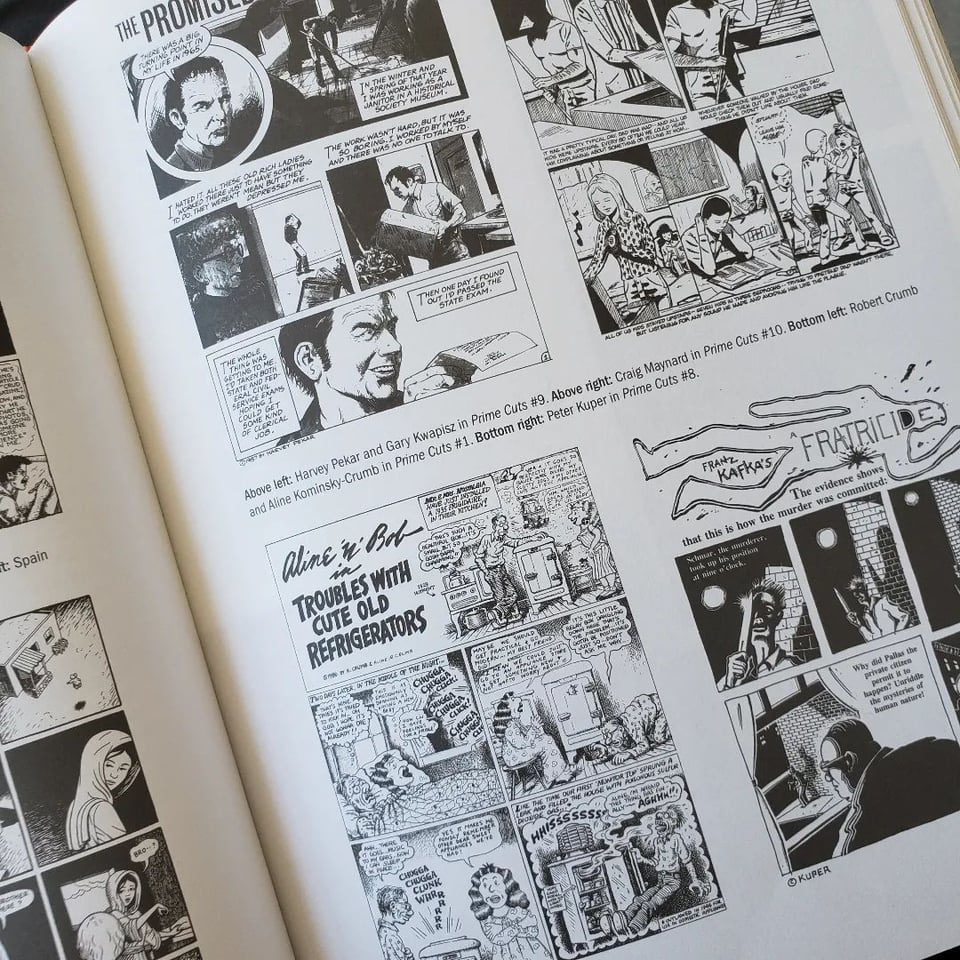

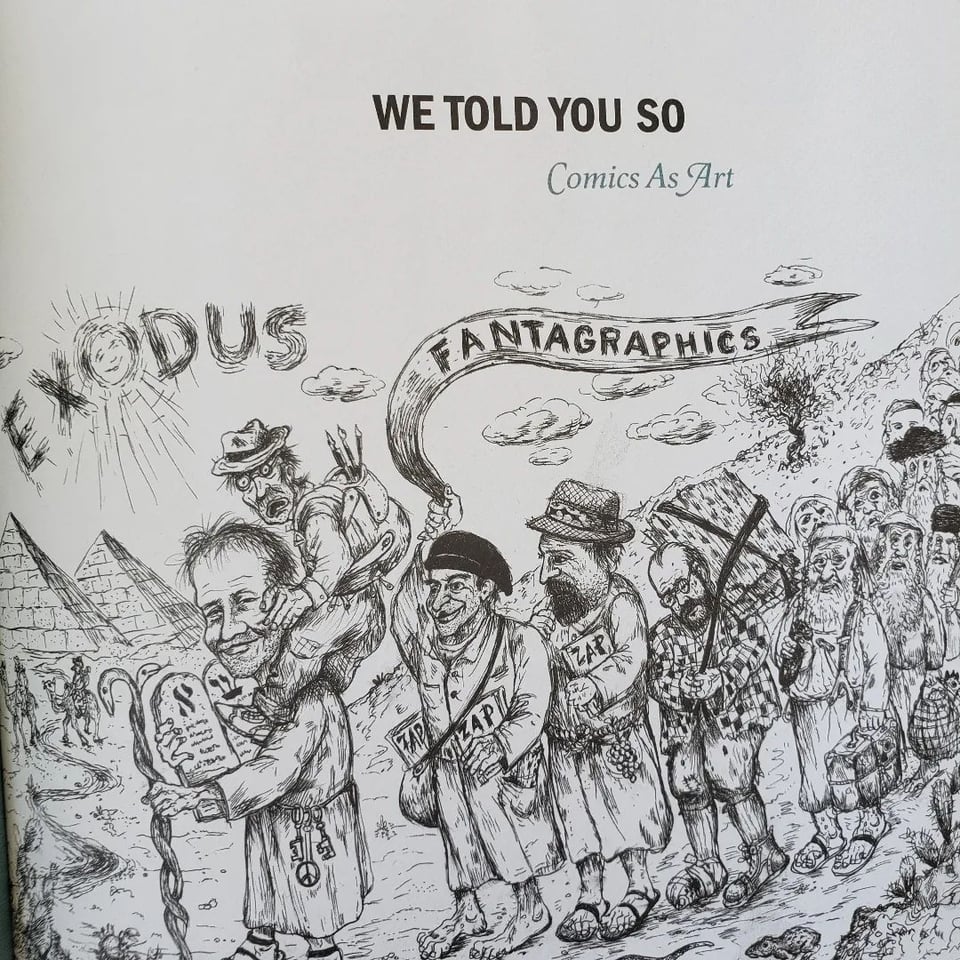

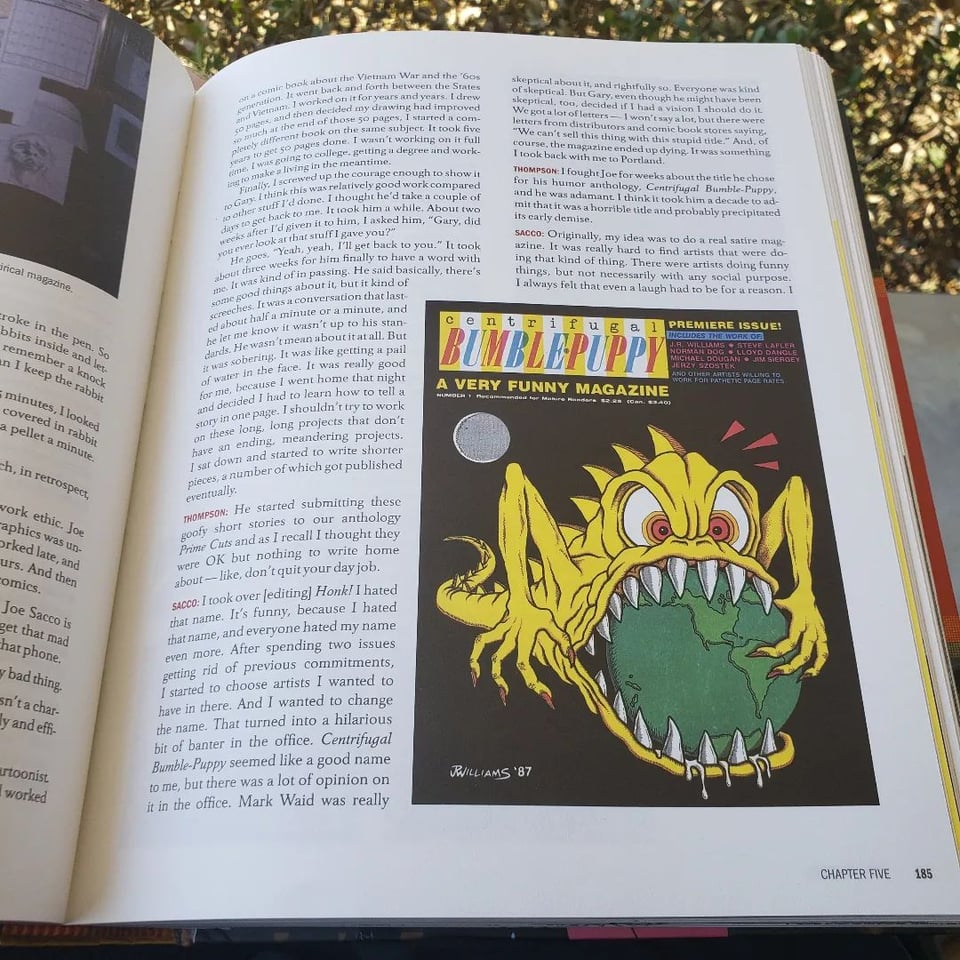

It’s also lavishly produced. In fact, the production values (something Fantagraphics is rightly known for) are the best thing about it. It looks fantastic, and the text is judiciously and generously illustrated with all manner of comics, photos, old advertisements, company memos, reader notes and much more. This is a tome published to celebrate 40 years of Fantagraphics and they obviously really cared about putting on a good show.

But the fact that this book IS a celebration is precisely the problem. It’s there in the title. Fantagraphics is here to tell you how fucking cool and hip it is, even after 40 years in business. In my more uncharitable moments – when wading through yet another paean to how Fantagraphics revolutionized comics; or when reading the fourth or fifth or twelfth anecdote about how co-founder Gary Groth liked to blow shit up with dynamite and shoot guns for kicks – I wanted to dismiss it all as a gratuitous exercise in public relations and toss We Told You So across the room.

Alas my arms were too weak and the book too heavy so I decided, because I was reading it for work anyway, to suck it up and finish the damn thing.

The most ironic thing is that We Told You So devotes pages and pages to detailing the exploits of The Comics Journal, the magazine that was the company's original flagship title, positioning TCJ as the radical conscience of comics. I've read old issues of the magazine and it has undeniably done invaluable investigative reporting and critical takedowns of comics that deserved scrutiny; but the kind of independent accountability for the industry that The Comics Journal, in its best incarnations, provided is lacking in this self-examination.

Even the attempts at self-critique that do exist feel hollow because most of those center on co-founder Gary Groth's reputation as an edgy asshole. This is by far the least interesting and least substantive critical issue to raise about Fantagraphics, but we hear about it over and over; some voices affirm it, most deny or qualify it; but the critique, such as it is, is ultimately rolled into the broader Fantagraphics mythos: Groth is unafraid to make enemies and willing to call out people for making what he sees as inferior comics. If some people think he's mean, well, whatever he did was in the iconoclastic spirit of improving the industry through caustic shock therapy. That’s the talking point, at least!

Alas, there is zero consideration of whether Fantagraphics’s contribution to the canonization of underground cartoonists like R. Crumb was anything other than a wholly good thing. There is also no reflection on whether Fantagraphics has contributed to the frankly barbaric working conditions in today’s comics industry. Oh, we get plenty of references to low pay, for cartoonists and employees alike, but there is always a justification — and because this is functionally an authorized biography of the company, not an independent account, there is no scrutiny applied, no hint of the skepticism that might've made this book genuinely valuable as a history.

Follow my bookstagram: @panthercitybooks