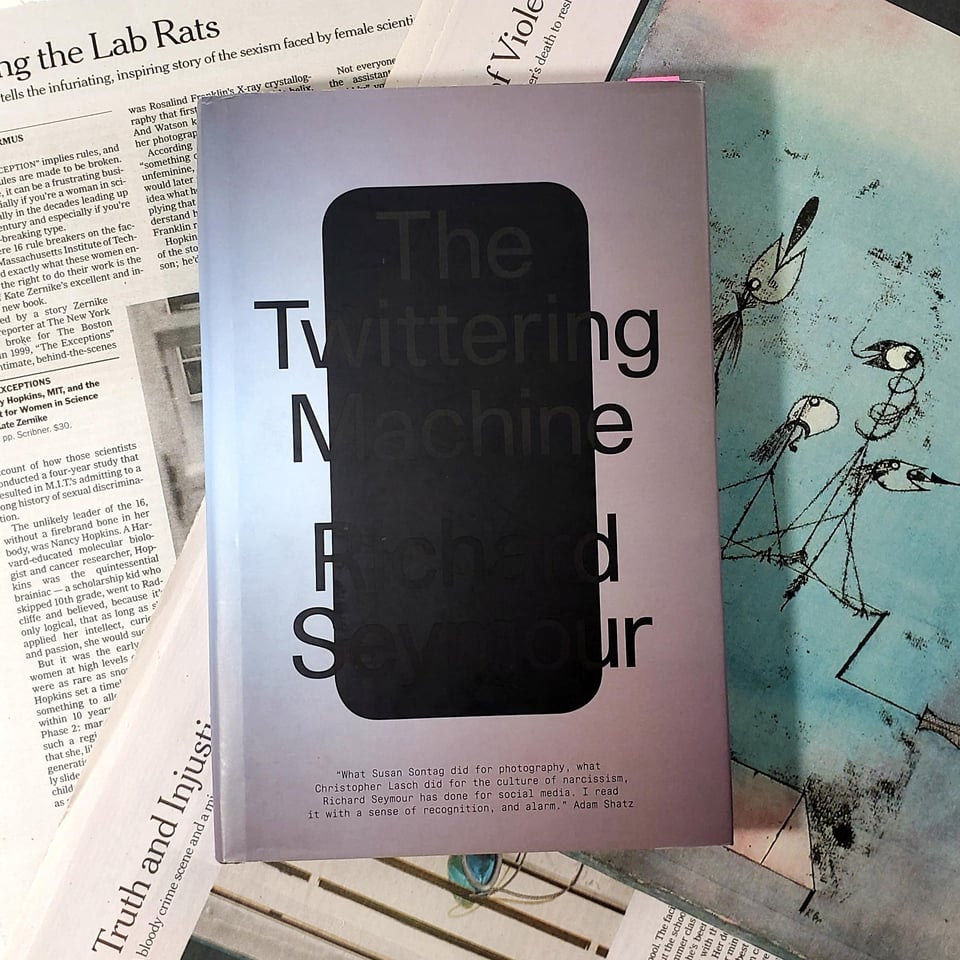

Review: The Twittering Machine (2020)

“If we’ve found ourselves addicted to social media, in spite or because of its frequent nastiness, as I have, then there is something in us that is waiting to be addicted. Something that social media potentiates.”

Richard Seymour’s The Twittering Machine is an important book for understanding the two-way relationship between humans and social media — the way we shape it, and the way it shapes us.

I feel like most cautionary writing about the internet and social media focuses narrowly on the latter and, in doing so, imbues the internet with overwhelming power: Smartphones are ruining the youths; Instagram is causing anxiety and depression; Russian ads on Facebook are what elected Donald Trump, etc.

The Twittering Machine, by contrast, offers a serious analysis of the conditions within society and within ourselves that lead people to become habitual users. Social media probably does worsen people’s depression, but Seymour argues that we also turn to it as a self-destructive form of self-medication, in part because the world we’re living in contains horrors that make it hard to “be present” in our lives at all times. (Just scolding people and telling them to “unplug” and “detox” feels inadequate without actually examining why people feel the need to plug in at all.)

I’ve read this book several times, but the launch of Threads made me want to revisit it. The Twittering Machine covers a vast number of subjects — fake news, trolling, celebrity, the power of the far-right online — but what struck me most on this read was Seymour’s focus on addiction and his comparison of social media to gambling. The book talks about the way gamblers invest their self-worth into abstract symbols: the dots on a pair of dice, or the stylized fruits of a slot machine. They look to such devices to tell them who they are. “In most cases,” Seymour writes, “the answer is brutal and swift: you are a loser and you are going home with nothing.”

For social media users, though, the gamble is a matter of words and images; you compose a post, send it into the world, and wait for the algorithm to determine your value through engagement: likes, retweets, comments.

Again, for most people, the answer is: You’re not worth much. This resonates with my own experience on the platforms, especially Twitter. I was never a good poster because I’d experience too much self-loathing and regret after most tweets, even those that did moderately well.

There’s a lot more to this book that I don’t have space to parse here. But it is definitely worth a read now, as Twitter dies and alternatives proliferate.

Follow my bookstagram: @panthercitybooks