Dead behind the eyeglasses

This post is sort of about augmented reality (AR). But the bigger point it’s grappling with is about who to trust when it comes to the development of technology.

If all of my grumbling and moralising gets too much, you can always scroll to the bottom to see one of my favourite (i.e. terrible) implementations of AR.

What ARe you talking about?

While I was doing background research, I found numerous explanations of augmented reality, often contradicting one another.

A simple description is that AR means the superimposing of text, images or video onto the ‘real world’ using a screen or other digital device.

The most recognisable form of AR is probably filters on social media apps – it’s the thing where you add a big bushy cartoon moustache onto your friend while you film them for your latest TikTok.

Non stop LOLz!

2024: a big year for augmented reality

On 25 September, the technology press was a-flutter when Meta unveiled their Orion augmented reality glasses.

It came hot on the heels of Snap announcing an update to their range of Spectacles – a product so ugly it looks like my 8-year-old designed it, only with less flair.

Meta’s big reveal, despite being accompanied by a barrage of PR, was notable for the fact that Orion "won’t make its way into the hands of consumers”.

It’s purely for show, a Purposeful Product Prototype no less (their awkward alliteration, not mine).

Presumably this was all about signaling to the markets that Meta is ON IT and busy inventing the future.

And no doubt why Mark Zuckerberg – wearing clothes so ugly it looked like my 8-year-old dressed him, only with less panache – was front and centre of the hype.

But haven’t we been here before?

2013: a big year for augmented reality

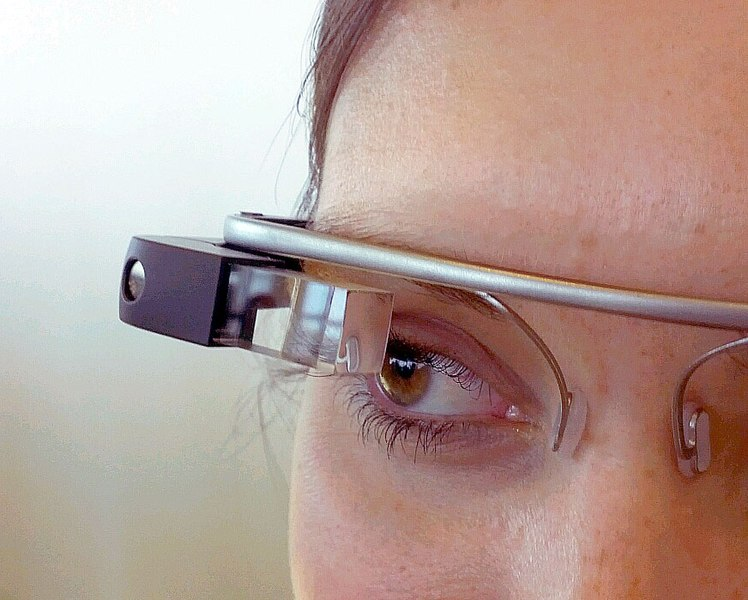

Google revealed their Glass Explorer product in April 2013, followed by a limited public release the following year.

There’s a nice summary of the short life of Google Glass on the Cooper Hewitt website, chronicling how the product was withdrawn in 2015 after “mixed reviews, negative press, and public outcry over privacy concerns” and going on to say “such devices raise ethical questions about acceptable personal and societal standards of transparency, privacy, and the potential for surveillance”

In the intervening period, thankfully, big tech has gone all out to remedy those concerns and comprehensively address any disquiet over privacy and personal information.

Oh wait. 😲

Google’s attempt to get ahead of the game with wearable AR was at least badged as a prototype, and withdrawn before a wider market release.

There’s an argument to be made that by virtue of simply existing, at a reasonably affordable price point, Glass enabled some experimental and innovative trials of wearable technology.

The Glass Wikipedia page, for instance, lists a number of applications in medical and hospital settings, where it’s easy to conjure a picture of hands-free access to data and information opening up some unique possibilities.

Dig deeper, however, and the results might not be quite as convincing. This research paper suggests the barriers were greater than many of the assumed benefits.

But haven’t we been here before?

1945: a big year for augmented reality

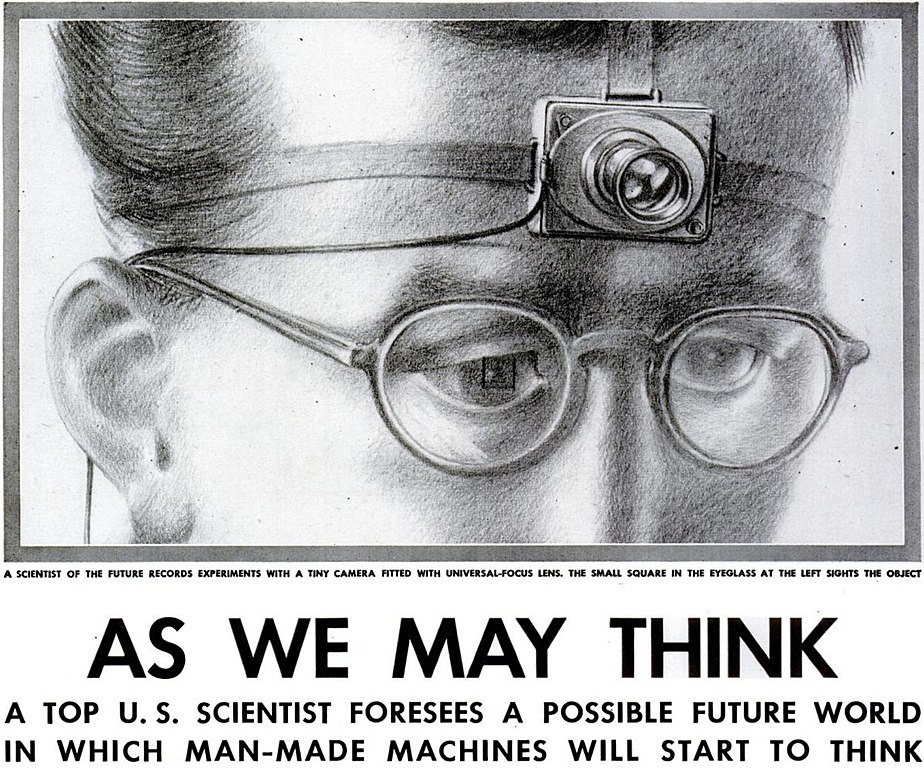

In his seminal 1945 essay As We May Think, Vannevar Bush, writing in The Atlantic, laid out his thinking on technology he believed would revolutionise society through the management of information.

It’s prescient on a number of fronts: the Internet, digital photography, speech recognition, and the mouse are all distinguishable in his description of the Memex, a futuristic machine he envisaged giving “scholars access to a huge, indexed repository of knowledge any section of which could be called up with a few keystrokes”.

Also present is his concept of a camera “a little larger than a walnut” – illustrated below, and not a million miles away from today’s product designs – which imagines a hands-free method of capturing information for research.

Bush, an engineer as well as an inventor, foresaw the use of such devices as being important for science and analysis, opening up new frontiers of discovery.

Meta, Google, and Snap (and while we’re at it let’s not forget Apple’s clunking white elephant) proffer no such clear-eyed vision for their wearables.

Instead they provide expensive answers to imagined problems, or new ways to surreptitiously hook us deeper into software ecosystems we’re already struggling to find our way out of.

We’ve definitely been here before.

In search of the missing use case

The point I’m unsubtly trying to make is that people have been busy imagining AR solutions (alongside its bedfellows mixed and virtual reality) for decades, yet there are still a lack of compelling use cases to draw on.

The main selling points often focus on lowest common denominator productivity hacks – Silicon Valley’s go-to when it comes to peddling its wares.

Not only does this obsession with cutting corners and easing the strain of everyday tasks generally fail to tackle real-world problems (Rachel Coldicutt’s thread on this is bang on the money) but it also habitually takes things that work reasonably well in real life and makes them worse.

Take these examples:

A worse office. Nick Clegg calling his Meta Quest “wretched” in the first few seconds probably tells you all you need to know; I wonder if he still runs his weekly team meetings in Horizon Worlds? 🤔

A worse dining experience. Ambassador, with this selection of 3D-rendered images of meals you're really spoiling us!

A worse calendar reminder. Unless you feel you can’t live without a pricey pair of glasses to prompt you to buy a book in a couple of weeks.

At best they suggest a woeful disconnect from reality – just imagine trying to transition your workforce onto VR headsets – as well as conveniently sidestepping the additional productivity overhead that come with new hardware and software: more devices and platforms to learn, to maintain, to charge, to sync, to update, to ponder what to do with when they’re obsolete.

When Zuckerberg blithely states “I think there will be this gradual shift to glasses becoming the main way we do computing” I can’t help calling bullshit.

There are no strong precedents, only hubris and spin.

Linking digital to physical

I was fortunate enough to work in a museum in the early 2010s when there was lots of interesting digital tinkering going on.

The rise of social media, the dawn of smartphones, and the availability of affordable, flexible hardware created a sweet spot where people were carrying out genuinely novel experiments to help broaden knowledge of, and engagement with, museum collections.

Museums offer a pretty special environment in which to try things out: self-contained buildings filled with unique objects, often with fascinating backstories. Plus a whole load of behind-the-scenes stuff that’s not on display.

This meant no shortage of offers when it came to technology suppliers and interested academics keen to see what digital possibilities could be unlocked, including use of location-based tech, voice recognition, and dalliances with QR codes.

We also played with some rudimentary augmented reality options using products like Google Cardboard, Wikitude and BlippAR.

Those were formative, and fun, times, but it was striking when we undertook user research how much pushback came from museum visitors.

Even back then, people felt overwhelmed by their digital lives: struggling with too many platforms, too many apps, too much information.

Any digital incursion had to feel worthwhile, encroach as little as possible, and offer a genuine value add.

Obviously I’m riffing off these examples from a very distinct situation, but it strikes me that the notion of augmenting or mixing reality – creating more clutter and noise, layering additional content and experiences – is at odds with what many people need or want in their day-to-day lives.

Why do I care?

I ask myself this a lot when I’m writing a post like this.

It’s wrapped up in much of what I’ve stated above, but the lack of honesty and humility play a big part.

From my woolly liberal soapbox I find the investment of tens of billions of dollars into fantasy hardware to be fundamentally at odds with the way I’d like to see technology change and improve the world.

When everyone’s on the ascendancy, nobody seems willing to think small and specific.

Big tech pumps the message that everything needs to be a game changer or a killer app rather than a well-honed solution.

Since the smartphone was unveiled 15 years ago, companies have been locked in hardware battles (glasses! headsets! robots! self-driving cars! spaceships!) desperate to secure the next big thing.

This leads to barely-functioning prototypes promising the earth then failing spectacularly, big pledges made on big stages that never come to fruition.

Augmented reality can work incredibly well when it’s set in the right context – Pokemon GO was mind-bogglingly successful – but it’s seemingly not enough to narrow the focus to gaming alone.

If you’re not heralding a revolution in the “main way we do computing” how can you possibly grab the headlines and rally the share price?

Casting all the way back to 1945, I’ll end with a quote from As We May Think:

"The world has arrived at an age of cheap complex devices of great reliability, and something is bound to come of it."

I (still) hope it’s a good something.

AR in the wild: the pinnacle of digital content experiences

👓 Thank you for reading

Add a comment: