Middle Ages? Yeah I sure hope it does

Or: How a '90s scifi book about a double plague kicked my brain's entire ass

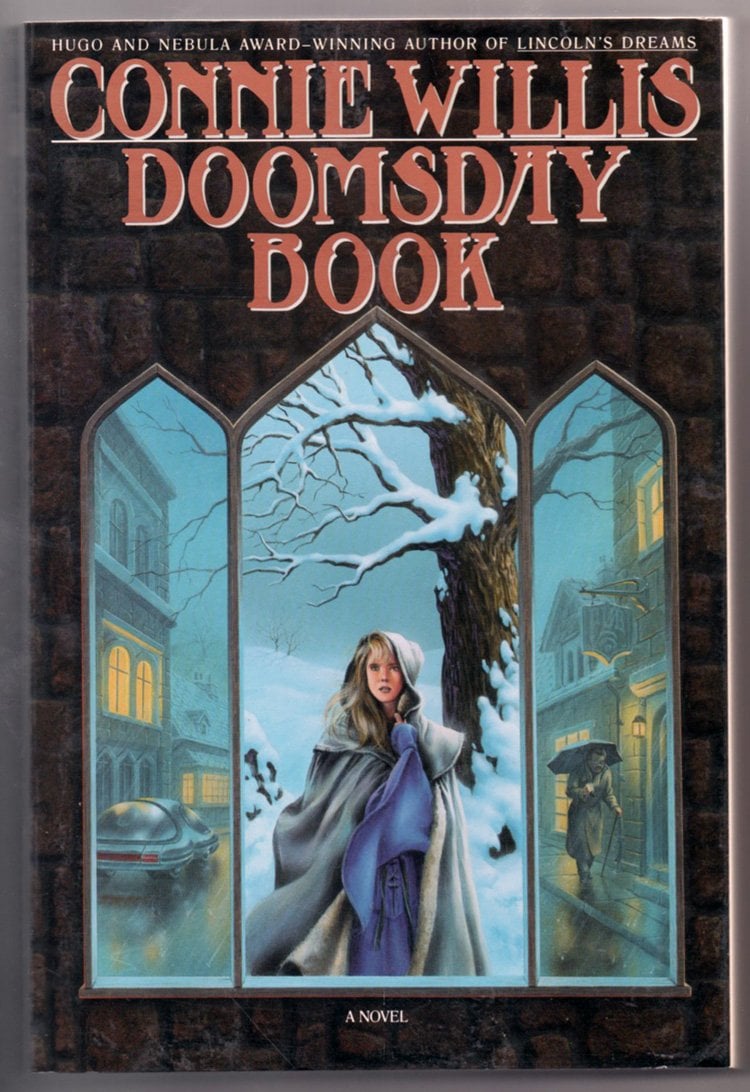

Guys. I don’t really have a plan for this week’s issue aside from telling you about this book I just read. With A Vengeance, Devil Three Times, and The Amalfi Curse all watched me ruefully with their quickly approaching library return dates as I picked up a book in a free bin based on the cover, took it home, and then lost two days of my life to its thrall.

The premise of Connie Willis’s Doomsday Book is that Oxford College’s history department in 2055 has access to time travel and uses it for academic research. The department’s archaeologist is working a dig in a medieval churchyard nearby and a student historian, Kivrin, with her intricately studied backstory and historically accurate clothes and meticulously dirtied fingernails, is going to 1320 to support the research.

The book is a perfect kind of dense paperback, just under 600 pages, and it somehow both takes its time and drops you right in the thick of it. On page 17, Kivrin is through the net and lying in a snowy glen, posing as a high-born woman who’s been a victim of highway robbery. She leaves behind an overprotective mentor, Mr. Dunworthy, who can’t shake the feeling that something terrible is going to happen to her, not least because the annoying bureaucrat heading the mission has eschewed safety checks and pushed the date up to get it done before his boss returns.

And that feeling! Was correct!

An hour after Kivrin vanishes, the sole engineer on campus able to monitor her location and bring her back collapses with a mystery sickness. This is notable because in 2055 illness has more or less been eliminated following a devastating pandemic that wiped out millions sometime in the past. This is when I checked the pub date and found that this book was published in 1992! I was ashudder! There’s a point where an American tourist complains about quarantine measures and brags about America not having any and someone says “well that’s why most of you died in the last pandemic” and what an incredibly powerful called shot.

Anyway, the engineer is sick, collapsing just after telling Dunworthy “something is wrong,” and nobody can find out what is wrong with Kivrin’s drop because no other engineers are on campus because it’s two days before Christmas. The way time travel works in this book is that it’s way easier to put someone back in time at the same time of year, and December has a lot of holy days so even peasants will be able to tell Kivrin the exact date she’s landed on and she’ll be able to make her rendezvous date, December 28th, the Feast of the Slaughter of the Innocents. The Christmas setting is something that really stuck with me. There are bells and snow everywhere, which is one of the things that makes this book so… well I’d struggle to use the word “cozy” without sounding like a psychopath because of all the death, but very tactile and vivid at least.

So to recap, the people in 2055 are dealing with a quickly spreading and very dangerous mystery virus, resulting in a quarantine lockdown and overflowing hospitals, just as Kivrin is landing in the woods in the 14th century and feeling a bit feverish.

In her disoriented state, she’s taken to a nearby village’s manor house and nursed back to health by a noble family and a hulking but well-meaning priest. Willis is so good at writing time travel that I felt like I time traveled to this snowy medieval village (I have read that Willis’ portrayal of the 14th century is maybe not the most rigorous, and watch me Not Giving a Shit!).

The first thing Kivrin’s aware of is the bells. All throughout the book she hears the bells from towers, in their church and in the surrounding villages, and the household’s little girl, Agnes, teaches her how to tell them apart by sound and location. The Osney bell always rings first, then Swindone to the southwest, and then twin bells at Courcy. Kivrin can’t understand the family at first, her Middle English tutor having completely beefed the pronunciation and her language mods taking a while to get up to speed. She takes care of the household’s two girls, playing with Agnes and her puppy and worrying over 12-year-old Rosemund’s arranged engagement. She has a recorder embedded in the bones of one hand so that she can press together her palms in front of her mouth so she can make notes and look, at a distance, like she’s praying. She rides a pony and attends midnight mass on Christmas as the mother-in-law of the house complains that the big priest didn’t make proper use of the candles she gave him. She worries about avoiding suspicion and finding the rendezvous spot in the woods and evading the mother-in-law’s attempts to have her sent to a nunnery.

And then there’s the second part of the book. One of the family’s Christmas houseguests falls ill. Kivrin sees a red swelling on his arm and finally learns that she’s not in 1320 but in 1348, when the Black Plague is about to decimate England, is already in her household. In 2055, Mr. Dunworthy comes to the same realization and struggles to come to Kivrin’s aid while the mystery flu accrues a steady death count and supplies run short in the quarantine zone, and Kivrin does her best to help these people she’s come to know struggle through incredible darkness, where death looms around every corner and hope flickers everywhere just to be extinguished again and again and it really does feel like the end of the world.

On one of her first days in the past, Kivrin has an existential crisis as she thinks about how all these people around her are dead now, 700 years later, but she still didn’t expect to be there to see them die. As Mr. Dunworthy makes a rescue plan, the archaeologist is digging through the old church cemetery, looking for a skeletal hand with a 21st-century recorder in it.

It’s hard to explain why I felt so attached to this book where so much dark stuff happens. It’s weird that a read with so much grief didn’t feel onerous or burdensome to me. I can offer you, as a pre-reader, a little comfort, but not much: Kivrin makes it, and so do Dunworthy and his child sidekick. These people in 1348 did die, were always going to have died, were dead 700 years before Kivrin was born. Does that make it better?

In 2021 I read a book about the Spanish Flu Epidemic (OK you got me I read an introduction to a book about the ghosts of Seattle’s Pike Place Market that was about the Spanish Flu Epidemic) and for some reason it brought me some kind of comfort. Like COVID wasn’t personal, it’s just what happens to you when you’re a part of history, and it was sad when it happened then and it’s sad when it’s happening now but ultimately it just affirms that we’re still people, just like them, and we’re not better or above them just because we have bluetooth now. Kivrin says something similar whenever her hosts ask why God is doing this to them. Nobody’s doing this, she says, it’s just a disease. This is just what it does. Even when what it does is unthinkable.

When Kivrin thinks there’s a real possibility that her bones are going to end up in the archaeological dig, she says into her recorder that she’s still glad she came. "If I hadn't,” she says, “They would have been all alone, and nobody would have ever known how frightened and brave and irreplaceable they all were." She looks at her palms, and considers a pin that Rosemund’s terrible fiancee gave her before he fucked off and with any luck died of plague off camera (most people did). The pin is engraved with Latin: Io suuicien lui damo amo. You are here in place of the friend I love.

The time mechanism in this book is supposed to shut down any paradoxes, not allow a traveler through if they’re going to change history, and in the machine’s view, nothing was changed. The dead still died. The gravestones remained. But something still changed, as Kivrin clasped her palms together and held the thought of the friends she loved and told their stories. Something was changed for the sick as they received comfort they weren’t supposed to have gotten, and for Kivrin as she engraved their faces into her memory. To be human is to engage, to change and be changed by each other. The witnessing makes a difference, for the witness and the witnessed.