Wherein I unhinge my jaw and Discworld thoughts issue forth in an unstoppable torrent

Everybody buckle up

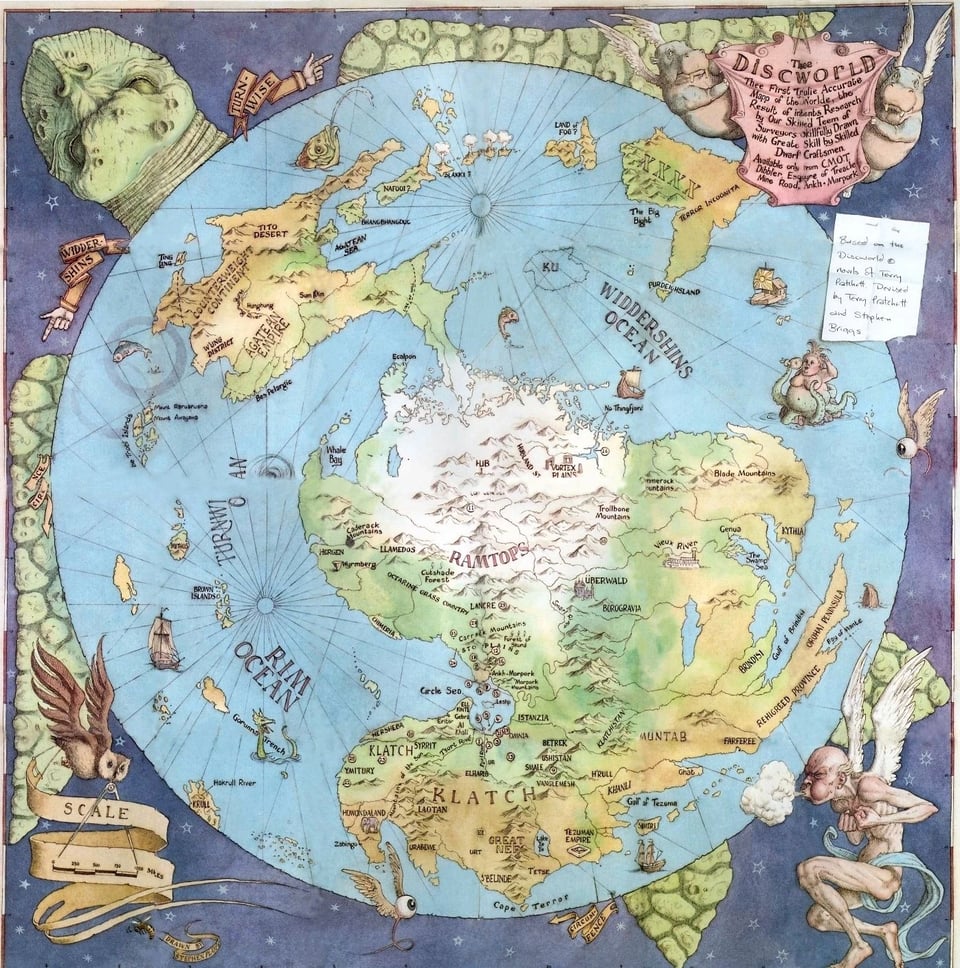

At the beginning of this year, someone I know mentioned that their bookclub was reading every book of Terry Pratchett’s fantasy Discworld Series in order. This struck me immediately as an insane thing to do. I’ve had these books in my life since I was born — my mom started picking them up at a secondhand bookstore downtown in her 20s — and I’ve never read them in order. Reading them in order isn’t as intuitive as it would be for other fantasy series because Pratchett’s focus swings, book to book for a grand total of 41, from the hapless wizard fleeing from Destiny to a scrappy underdog captain of a city guard’s night shift to a trio of witches protecting their tiny kingdom in the remote mountains. He fixes his gaze on different tropes, genres, and cultural artifacts so you can get everything out of his work from a hard-boiled murder mystery noir to a twisted retelling of Midsummer Night’s Dream to conceptual time-traveling quasi-scifi. All this to say, reading them all in order doesn’t make a lot of sense. But just being aware that someone was doing that made me start thinking about doing that and now I’m doing that too, so let that be a cautionary tale about talking to people about their book clubs.

I’ve been a little delayed on putting out issues of this newsletter lately and that’s because this is mostly what I’m reading right now (I’m currently on #31) and I struggle to find a way to start to talk about it. It’s like trying to tell someone what’s so good about the concept of having tastebuds. What am I going to do, list my favorite characters? That defeats the purpose, because their context is what makes them so great! If I just tell you that one of my favorite characters is a dwarf named Cheery Littlebottom with no pretext or chaser, what are you even supposed to do with that??

A list of my favorite books would either include like 35 out of 40 and thus be super useless or would be shorter and give me heart palpitations over the equally excellent ones I didn’t include. I started trying to keep a list of my favorite minor characters, but so far that list is just You Bastard, a camel from “Pyramids” who is ontologically evil and, though he cannot speak, is secretly the world’s greatest mathematician, and a rat that is kept as a fancy pet by an aristocratic vampire and wears a fluffy pink bow like it’s a Bichon Frisé.

So I guess I’m just going to tell you why Pratchett is so special to me, why a world full of trolls and dwarves and talking dogs has me in such a stranglehold.

Pratchett uses these fantastical trappings and a prodding humor to interrogate what makes us human. I think what was so impressive about him was how much he thought about everything.

Obviously the word ‘neurodiversity’ wasn’t necessarily around when he was writing, and yet his world holds an incredible amount of different kinds of brains. Dwarves tend to be pragmatic, intensely detail-oriented, and heavily literal (a product of never seeing the sky and the unrelenting prioritization of avoiding cave-ins over less pressing matters like emotions). Tiffany, the young witch of Pratchett’s YA series¹, has Second Thoughts, which are how she thinks about what she’s thinking, and is troubled by how much easier it is for her to think about thinking about thinking about things than it is to feel anything. A character describes her as the person at the party with the drink in the corner who can’t join in, a little part of her that refuses to melt and flow. Otto Von Chriek² is a vampire who works for a city newspaper as a photographer (YES THERE ARE PHOTOGRAPHERS IN DISCWORLD BUT THEY’RE CALLED SOMETHING ELSE AND BASICALLY IT’S A BOX WITH GREMLINS IN IT), having transferred his addiction to blood into an obsessive dedication to light and a supernatural compulsion for capturing it on film.

The anthropomorphic personification of Death, responsible for shuttling the dead off to whatever comes next, finds humanity rubbing off on him while also being mystified by it. His adopted granddaughter (it’s complicated) is intrigued by touches he makes in the house he’s created for himself, including a bathroom he doesn’t need filled with silver hairbrushes and untouched soap and a rubber duck. “He wanted to be more than a bony apparition. He tried to create these flashes of personality but somehow they betrayed themselves, they tried too hard, like an adolescent boy going out and wearing an after-shave called ‘Rampant.’ Grandfather always got things wrong. He saw life from outside and never understood.”

When he’s around humans outside of his professional capacity, Death is amazed at the way they’re able to invent boredom in a world full of marvels and struggles to understand the idiomatic ways that humans talk around literal truths, confused by the phrase “we lost him” to describe a death. He is deeply unsettled by humans’ tendency to keep clocks around, the endless ticking serving as an audible reminder of each second of life slipping past. He is more or less entirely lost among the web of inventions humans use to keep themselves insulated from an incomprehensibly yawning eternity and I might be revealing a bit too much about myself when I call this relatable. “He doesn’t know how to forget things or ignore things,” his granddaughter says. “He takes everything literally and logically and doesn’t understand why that doesn’t always work.”

And GENDER???? Don’t even get me STARTED (this is rhetorical; there is no way to prevent me from getting started on this). In his third book, Equal Rites, Pratchett explores the difference between witches and wizards (and it’s not the Michael Scott difference I promise). He sets up wizards as hegemonic and academic, holed up in a university and concerned with the macro and the micro, subatomic magics and the demon dimensions, theory and calculations. Witches, on the other hand, are more like cats: solipsistic, opinionated, and opposed to organization of any kind. “The natural size of a coven is one,” Pratchett says.³ “Your average witch is not, by nature, a social animal as far as other witches are concerned. There's a conflict of dominant personalities. There's a group of ringleaders without a ring.” They’re down-to-earth and practical, tending the unglamorous toil of births and deathbeds, less concerned with theory and even with the practice of magic when they know that usually what people need is just a handful of ordinary herbs or being told not to pick at something, with just enough witchy presentation to make them take the advice seriously. The witches’ power is in the magic they don’t use.

And yet, as he sets up this divide, Pratchett also bridges it with his protagonist, Esk, a girl assigned Wizard at birth. A wizard hears of a seventh son being born to a seventh son (which is how wizards are made) and passes along his staff, dying before he can realize that this son is a daughter. Esk spends the book torn between two worlds, feeling not quite right learning hedge magic from a witch but bristling at the rigidity of wizardry as well. Her response to this binary, if you will, is to reject it. “She’d be both, or none at all. And the more they intended to stop her, the more she wanted it. She’d be a witch and a wizard too. And she would show them.”

Pratchett’s dwarves only have one gender presentation. Male or female, all dwarves just identify as “dwarf,” use male pronouns, wear the same chain mail and beards, and only really worry about sex differences in a discrete sort of way when they need to make more dwarves. Over a few books in the series we see the path of presumably the first dwarf to identify as female⁴, timidly starting to wear lipstick and earrings and a kilt (but never shaving the beard because she still has dwarf pride, after all) and to me this is some of Pratchett’s most prescient writing. She is met with shock and, often, revulsion from other dwarves who bristle at her presentation and her choice of pronouns, resentful of the change she represents. She is the recipient of scorn and nonunderstanding from more conservative dwarves, but at the same time her resolute insistence on who she is becomes infectious and everywhere she goes, closeted female dwarves start to grapple with what they could be and start to consider the thrall of sequins and mascara. At one point her most vitriolic opponent is a powerful dwarf who, it turns out, is female herself and boiling with jealousy that someone else made a gender choice she felt like she couldn’t. It is probably not surprising to you that trans readers have flocked to Pratchett’s work and experienced a probably far more rewarding experience than maybe some other fantasy franchises that we are all picturing right now!!!

Lastly, I want to talk a little about religion in the Discworld books. Or, I guess, more dogma, because gods are a known quantity and philosophers in the Discworld who want to debate their existence know to stay away from trees or particularly conductive metals while doing so. Small Gods, about a god who loses control of his massive following, accidentally becomes embodied as a turtle, and tries desperately to keep his one precious remaining follower from getting got by the inquisition, is huge for this, but I found myself particularly snagged on another book this time around: Feet of Clay. This is one of the books that follows the night watch in the sprawling, pre-industrial London-esque city of Ankh Morpork, and it introduces golems: hulking beings made from clay and designed for labor, more machine than person, with commandments written in their heads that mandate their behavior and forbid them from doing harm. There’s a lot of anticapitalist stuff you could talk about with the golems, humanoids with no humanity, a distillation of the commodity of labor, but I’m not smart enough to do any of that. This book is a murder mystery and nobody suspects the golems, who are everywhere, because the words in their heads forbid them from murder. They are speechless and as overlooked as furniture, despite their intimidating frames.

But golems have hopes and dreams, and we find out what golems mean to themselves when one’s commandments are taken out of his head and replaced with his own bill of sale, telling him that he now belongs to himself. It reminds me of the stuttering step we take into the real world, whether we were raised religiously or not: the fear and freedom that come from the responsibility and the opportunity to make choices based on our values instead of trying to cling to a list of rules that were duct-taped to us as children. Mr. Dorfl is the first golem capable of speaking, and he gleefully engages with each choice he is now capable of fully making. “I Could Kill You,” he says when he apprehends a killer at the end of the book. “This Is An Option Available To Me As A Free-Thinking Individual But I Will Not Do So Because I Own Myself And I Have Made A Moral Choice.” This is how we all become human, I think, we’re just not usually as aware of it.

Discworld: A beginner’s guide

If any of this has not made you run screaming away from this newsletter and perhaps the pursuit of literacy entirely and instead made you interested in picking up a Discworld book, here’s a little primer for places to start in this hulking canon. It is my official recommendation not to start from the beginning and read them all the way through, this is only OK for me to do because of the worms in my brain.

The Night Watch: If you liked hearing about dwarf gender and golems or even just like the idea of murder mysteries and a protagonist who harnesses the power of being a scrappy bastard for good, I’d recommend reading some of the Night Watch arc, which starts good and only gets better. The first book is Guards! Guards!

The Witches: If you liked the description of witches as cats, get ready to meet some incredible cats. This arc starts with Wyrd Sisters, where the witches find themselves dealing with an increasingly unhinged Macbeth type trying to take over their tiny kingdom, and is followed up by Witches Abroad, where they desperately try to prevent the plot of Cinderella from unfolding!

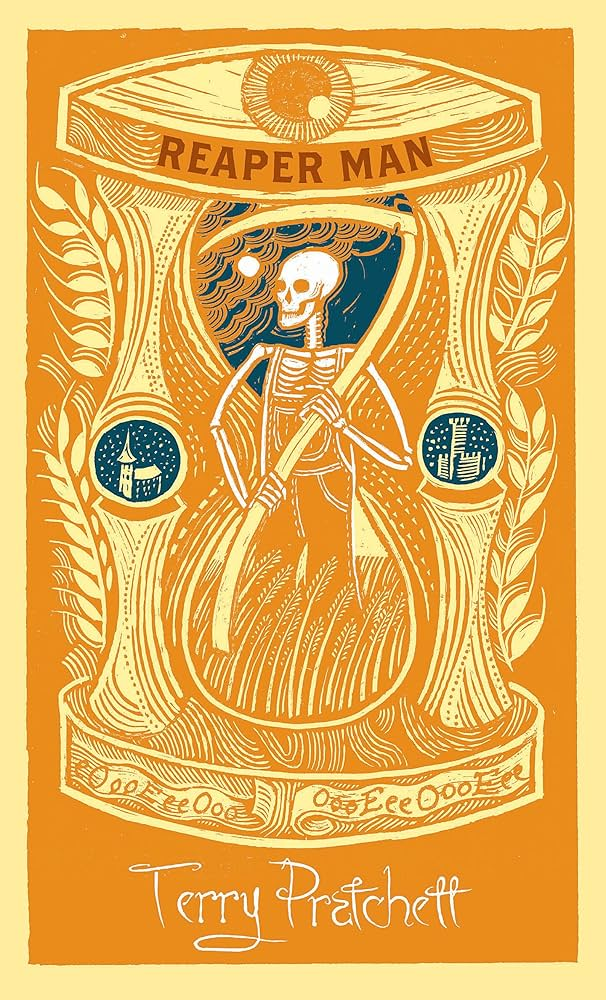

Death: If you want to know more about this crazy guy I actually wouldn’t start with his first appearance, Mort, because I’ve just never really been a Mort guy. I like Reaper Man, where Death quits (wouldn’t you?) and tries to live on a farm with humans. You could even start with Hogfather. (Hogfather is the Discworld analogue of Santa Claus and in this book Death has to fill in for him and deliver presents to children while he enlists his granddaughter to save the Hogfather from being assassinated. It fucks super hard and there’s also a movie of it that my family watches every Christmas and this might explain something about me.) After Hogfather you legally have to read Thief of Time which is one of the best books ever and which I can’t explain anything about until you’ve been properly Hogfatherpilled.

An out-of-pocket place to start: I’ve never seen anyone but me recommend this but I assert that Monstrous Regiment works well enough as a standalone despite being pretty deep in the series (#31). It covers a girl who disguises herself as a boy and enlists in the losing army of her backwoods country in the hopes of being reunited with her brother and it is so gender (complimentary).

FOOTNOTES: Here are where some of the above mentioned characters appear for easy reference

Tiffany Aching appears in Wee Free Men, A Hat Full of Sky, Wintersmith, and I Shall Wear Midnight. These are technically billed as YA books but are every bit as thoughtful and provocative as his adult fare. There are rumors she is also featured in The Shepherd's Crown, which is Pratchett’s last book and was published posthumously, but I wouldn’t know because I myself will never read it because of my fear of finality!

Otto Von Chriek is featured in The Truth, also appears in Monstrous Regiment, Going Postal, Thud!, and Making Money.

Witches Abroad

Cheri Littlebottom (SHUT UP) most prominently appears in Feet of Clay, Jingo, The Fifth Elephant, and Thud!. She’s the forensic expert for the night watch (YES THEY HAVE FORENSICS) and I love her.