The end of Ghibli

(This email contains spoilers for The Boy and the Heron.)

‘Ghibli is just a random name I got from an airplane.’

So says Hayao Miyazaki in 2013’s The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, a documentary supposedly following the studio through the making of their two 2013 releases, The Wind Rises (dir. Miyazaki) and The Tale of Princess Kaguya (dir. Isao Takahata). I say supposedly because the film, in reality, focuses almost entirely on Miyazaki and the staff working on The Wind Rises; Studio Ghibli operates two studios on opposite sides of the same town, and while Mami Sunada was following Miyazaki and his staff around one, Princess Kaguya was being made at the other. Most of the film’s view of Takahata’s production is mediated by Miyazaki and his producer, Ghibli's third co-founder Toshio Suzuki, where Miyazaki is mercurial in his descriptions of his mentor (he describes him both as having ‘genius’ and a ‘personality disorder’) and Suzuki is more stark in his assessment (‘How should I put this? He’s never delivered a film on time or on budget’). The sense I was left with by the documentary was that Ghibli is not the stable entity we might expect such a cultural juggernaut to be. The documentary camera lingers over piles of merchandise as Suzuki frets about whether Takahata can be persuaded to finish his final film at all and Miyazaki wonders to himself, flipping between animatics, ‘I’m not sure we have a film here’.

I came to watch The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness after seeing Miyazaki’s latest, his second ‘final film’, The Boy and the Heron, for the second time. It is, for me, a wonderful and quite beautiful movie: a meditation on loss and on continuing to live, pitched as a great master’s farewell to his medium and, reportedly, to his late mentor (Takahata, who brought Miyazaki to prominence in the years before the founding of Studio Ghibli, passed away in 2018). Between my first and second viewings of the film, my grandmother ended her long struggle with cancer, and although I was impressed by it when I first saw it in October, that loss gave the film a new poignancy when I saw the all-star dub in the week before going home for the funeral. The opening, in which a young Mahito runs through a burning Tokyo to try and save his mother in an air raid, is some of Miyazaki’s most daring animation, eschewing the defined lines of his usual style for more watercolour evocations, and the succession of images and set pieces that define the plot work more on the subconscious than by conventional rules of narrative progression, much as grief, I have found, refuses to be compartmentalised or narrated in any simple way. It is occasionally bewildering but it is also very beautiful.

There is material here for a biographical reading of the film - not only does it seem commonplace to observe that Mahito, the Grey Heron and the Granduncle are reflections of Miyazaki, Suzuki and Takahata, but Mahito’s father, like Miyazaki’s, manufactures planes - but I find these to be flattening, the kind of thing I would warn my undergrad students against. Extracting Miyazaki’s feelings towards his mentor from the film seems a missed opportunity. If you want to know something about their working relationship, you can watch the documentary and try to distill it from there, and I wish you luck, but a film that merely allegorised a working relationship would be a poor film indeed.

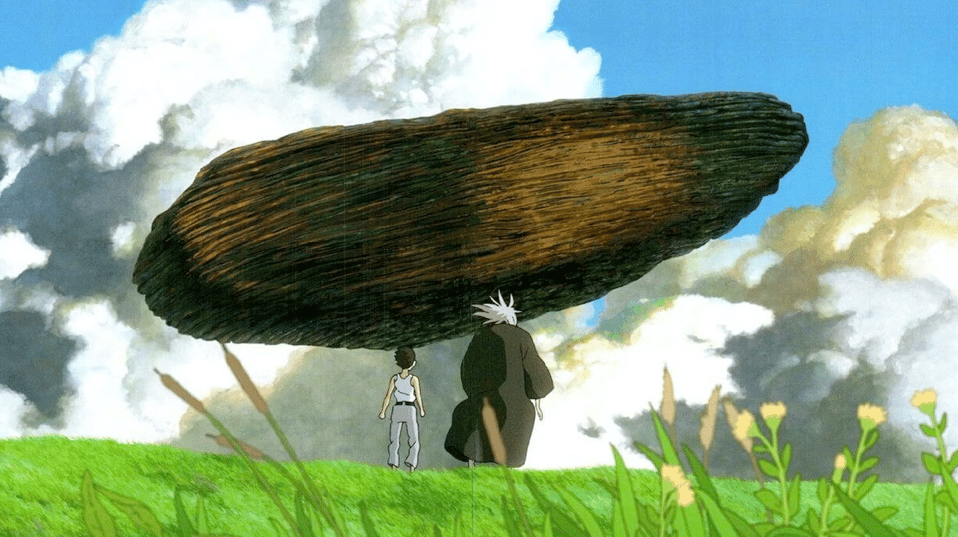

The Boy and the Heron does, I think, have something to say about making art that is very apt for a supposed ‘final film’ (reportedly Miyazaki is already back in the studio, but I personally doubt he’ll manage another feature). The film’s climax revolves around Mahito’s grand-uncle, a wizened, demiurgic figure who seems to rule over the set of worlds Mahito and his friend Himi have been exploring, and his request that Mahito succeed him as the power that holds them together. This power is expressed in a set of stone blocks that the grand-uncle stacks and re-stacks to ensure the continuity of these worlds. Mahito is confronted with this choice twice; first, in a dream, he handles the blocks and senses that they are full of malice, and he refuses to use them. Later, he meets with his grand-uncle again, who offers him a new set of blocks, but Mahito again refuses. I don’t think it’s a stretch to see the stacking of blocks, an allegorical act of creation, as symbolic of making art, and repeatedly stacking and re-stacking them as something resembling an artistic career. But there are things about this that are interesting to me. In order to build a new tower with the blocks, the previous tower must be destroyed: the iterative process is also cyclical. And the blocks themselves are, says Mahito, imbued with malice. In the earlier documentary, Miyazaki describes The Wind Rises as being about how making things can always be consumed by dominant forces - the film itself is about a plane designer who winds up working for the Japanese war machine, but Miyazaki says this can happen with anything, ‘animation, too’. I see this current being picked up in the vessel of the stone blocks, a tool that has become corrupted. And an identical set, supposedly free from malice, does not work for Mahito either.

It is hard, then, not to parallel the collapse of the alternate worlds Mahito visits with the collapse of Studio Ghibli. I am referencing Miyazaki’s own beliefs, here: in the same conversation where he remarked to Mami Sunada that Ghibli is ‘just a name’, he predicts that the studio will, in time, fall apart. Perhaps this was a little premature - the two films they released in the ten years between Miyazaki’s two final films is quite a standard pace of production for them - but I don’t think he was wrong.

Let’s look a little closer at Ghibli’s filmography. Most of their films have indeed been directed by either Hayao Miyazaki or Isao Takahata; three of their films, including one of the two between 2013 and 2023, as well has their only television series, have been directed by Miyazaki’s son, Goro. Only five others, all men, have ever directed for the studio, and one of those, Hiromasa Yonebayashi, has since founded Studio Ponoc, which is staffed by a number of Ghibli veterans. Studio Ghibli, is, then, a vehicle primarily for its founders, and the two surviving founders are in their seventies and eighties. There are no presumed successors to either of them, aside from Goro Miyazaki, whose increasing use of CGI continues to divide critics. But what I am trying to say here is that this might not be a bad thing.

Returning to the blocks: in The Boy and The Heron it is in destruction that new worlds are made. Studio Ghibli came about in part because Takahata and Miyazaki senior had exceeded what they could do at other studios, and Miyazaki had outgrown working under his mentor. (This is floated by several in The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness as the source of their fractious relationship, and once both have finished their films they can be seen laughing together on the roof of the studio building.) And we can see this happening again with Studio Ponoc, who have already released three films in Japan; the third, The Imaginary, was reportedly held up by a number of key staff pausing their work to help Ghibli complete The Boy and the Heron, so relations between Yonebayashi and Miyazaki seem rather better than between Miyazaki and Takahata. The blocks are knocked down: the blocks are built back up. If the fire that consumes the world at the close of the film is the demise of Ghibli, it is important that this collapse is not something sad, or terrible, or even truly destructive. Everyone in The Boy and the Heron ends up exactly where they are meant to be. The end of Ghibli can be like that. And I think Hayao Miyazaki knew that ten years ago.