“We need to be deriched.”

Now there are some who think they confute a speaker the moment they ask,“What then ought we to do?” To these I will give the fairest and truest answer: Not what you are doing now. I will not, however, shrink from going carefully into details; only they must be as willing to act as they are eager to question.

—Demosthenese, on the decline of ancient Athens

Greetings from Pressed Café in snowy Manchester, NH.

I never got around to writing a summary of the (2023) Year of Anti-Inflation, though it sufficeth to say that it was a smashing success. (Try saying "sufficeth" even twice in a row; I find that if I try I lose the ability to say it even once.) I really enjoyed everything about anti-inflation. And like any truly good New Year's resolution, it never really ends and shall carry forth in dividends.

Now that I think of it, I don’t recall if I ever mentioned that one of the central parts of that year was a commitment to buying absolutely nothing new for the whole year. And that practice was a smashing success as well — at least for me. Meghan was wholly onboard until a certain someone started rapidly dividing cells, but still stayed the course pretty well. And we did leave Montana with a carload of entirely used baby clothes and accessories from coworkers there.

I may no longer have a rule about buying absolutely nothing new, but the rule was always a means to the meaning behind it. (Hence why the rule didn’t get much attention.) Though the temporary rule in this case may not be essential, having a (sometimes extreme) method of channeling what you’re after is… well, I guess it might be at least temporarily essential. It might be that unless you really make yourself refuse to buy new things, you aren’t giving yourself the opportunity to discover just how fine you are with what you have. For example, I spent most of the year — our time out in Montana, plus some — using only the clothes I had packed into one carry-on bag for the car, which, I discovered, was more than enough.

What’s more — and more essential — is the discovery that the things in our lives, all of those plain ol’ things, should and can be loved. Not obsessed over, idolized, or clung to, but loved. And they can’t be loved if they are constantly replaced — or possessed as replaceable.

I think if this is practiced well, you may one day find yourself smiling from within any of a hundred different feedback loops of loving care and satisfaction in the simplest overlookable physical things. I have certainly found this to be the case, even within my own snail-paced and wildly haphazard attempts to love things, to treat them as things that can’t be computed or monetized. And hopefully all those small things, along with the world they come from and exist in, will not continuously inflate but instead hold their value in a society that’s having a hard time finding any fixed value at all.

After a little carburetor care, and now just shy of her 20th birthday, Tyrannus T. Twostroke is still huckin’ snow.

Last year was significantly more wandering and unresolved. I had some early plans and energy for a sort of combination of “putting your money where your mouth is” / personal “dogfooding” / killing the “monkey mind.” As you can probably guess, this had mostly to do with getting away from the smart phone. People have different feelings about the jealous and spying little pocket device we for some reason still call a phone, but my primary motivation is the fact that every single day away from it is better than a day with it.

I have written at short length — and talked ad nauseam — about how much I despise Google, and Apple, and smart phones, and social media, and algorithms, and blah, blah, blah. And Meghan and I have been in the process of finding out just how serious we are about these things. But it’s an admittedly long and clumsy process.

I had set up a Tracfone last year, to give myself a cheap option of being reachable without being “connected” or distracted. And I really can’t overemphasize what I have in mind when I talk about avoiding distraction. Even a random dandelion in a crack in the sidewalk, for instance, is worth my time, worth not being distracted from, worth noticing, no less so than some lone sunflower by the side of the road in an Arizona desert that seemed worthy of a photo op.

(Irrespective of the age we live in, it does seem a tragedy to have the one type of attention — the one that bags and tags — without having much of the other type of attention — the unrecording, circumambient peripheral vision.)

I gave myself a lot of leeway on the smart phone, which was at first a helpful grace period; switching back to a flip phone after a decade is a big adjustment, especially for an addicted article read-laterer like myself. But leeway gave way to excuses, and by the time I was driving 5+ hours every week and bringing podcasts back into my life with a vengeance (it was an election year!) and needing to navigate a new city and having to enter work hours on an app — well, the whole thing was a bust. I don’t think I even turned the Tracfone on once in the second half of 2024.

But that’s okay. With job things being up in the air, the new/old house being a new/old house, and not-so-little Baby Boy hurtling into toddlerhood, I didn’t really have the bandwidth to do much more than take notes and project my ideals down the road a bit.

God willing, I will kick that specific “phone”-shaped can along no further than March. I’ll say more on this in the future, but I’m hoping that, after a few delays with the new Light Phone III, Christmas will finally come in another month.

I’m really excited about what the Light Phone folks are trying to do.

Naturally, having the aforementioned Tasmanian Bumble bouncing around the house is pretty good motivation for getting your act together. I can send the sun down the sky making excuses for myself; with him, I have no excuses. This boy sees what we’re up to.

And let me tell you, Will notices — everything. He notices, for example, when I growl at a tool or at some plan that is probably only momentarily not working the way I want it to and then, after seeing him staring at me in curiosity, pretend to play it off like I was just making the sound a bear makes. (He doesn’t buy it, probably because it seems even dumber in person than it does written out here.)

And of course he notices when my big dumb still-face is staring at the tyrannous rectangle. And no, he doesn’t care if my big dumb still-face was looking up a recipe or just reading an article. (Probably an article about my big dumb still-face, which is not a thing I made up.)

He also notices the different ways we play music.

One way he sees it is that, seemingly without touching any visible buttons or knobs, we power on a little free-floating gray speaker, about the size of the can of seltzer water on my café neighbor’s table and that usually hides (like an empty can of seltzer water) unregarded among any of a dozen homeless piles of clutter around the house, which then “baloops” on and starts streaming (whatever the hell that means) from that always-new-and-replaceable-rectangular-extension-of-your-body-that-you-never-don’t-have.

And boom, we’re listening to literally anything from anywhere.

Contrast that friction-free music experience with the wobbly patter of a pair of one-year-old feet excitedly walking over 100-year-old wide-board pine floors to the white painted hutch where the 25-year-old JVC CD player sits on top of the 50-year-old, 30-pound Pioneer receiver, and helping yank open the top drawer of the hutch that always sticks, pulling out the Trapper Keeper of a CD case from under the dish towels, flipping past the pink and red circles of the Goo Goo Dolls, the orange and yellow Counting Crows, and that black and red 10 Years album that his dad bought at the BX of Al Udeid Air Base in Doha in 2005 just by judging the cover, then finally seeing Collective Soul’s Disciplined Breakdown slide out of its pouch, and, with the click of the power button that annoyingly inches the CD player back each time, watching the cheap neon blue light up the digital display as it powers on and, mimicking the look of a turntable, gears opens the clear cover of the CD tray, then snapping the disc around those taken-for-granted spring-loaded ball bearings that hold it in place and watching the cover close and hearing the whirr and chirp and “t’jit-t’jit-t’jit” as the laser searches and the filigree cover art swirls and blurs away…

And then the music plays.

Is one of those two options better? Do you suppose my son notices the difference? (Do you suppose I have noticed the difference?)

Do you suppose one of these methods creates more space for a thing to love?

Disclaimers and exceptions of time and place notwithstanding, I’m going to go out on a limb and say that for anybody, but especially for a new and excited soul freshly wandering into embodied life on this planet, there is no contest here.

I’m not quite bold enough to say that the balooping bluetooth’s days are numbered (most of even the type of music I listen to these days I don’t have on CD…yet), but its time will certainly be limited. And it will remain the only bluetooth speaker we have while attention gets put back on the more physical manifestation of music in the house. My plan right now is to use it mainly when I’m listening to podcasts at home, which is itself a pretty rare thing.

Oh, and that 1972 Pioneer receiver I mentioned — we found it on Craigslist in Biddeford a week after Will was born. Yes, it really does weigh 30 pounds; yes, it still works perfectly at 53 years old; and yes, it’s beautiful:

The decades-old nostolgia this thing brings with it is wonderful. Touch screen? Haptics? Pshh. I’ll take clicky buttons, snappy knobs, and a heavy tuning dial. Seriously, I don’t know how they do it but that big tuning dial on the right feels like it has half-pound weights on a pulley behind it. When Clare Coffey wrote her excellent essay “Things Used to Work in This Country,” this is the kind of thing she had in mind. I tried to offer a lower-than-asking price when I first reached out to the seller, but the guy shot back with a very clear, “Don’t try and lowball me, son; I know what I have.”

Another fun part of this project I’ve mentioned before is the print-to-read stuff. Last year I added a Brother laser printer to the desk and discovered an option to “print as pamphlet,” which automatically rearranges the pages so you can just fold the printed pile in half and, voilà:

Uses less paper and ink/toner, easier to pack and carry around, and of course, reminiscent of those church bulletins at First Baptist in Hallowell that were so educational…ly useful for playing Tic-Tac-Toe or Dots ‘n Boxes during the sermon. (So, clearly this printing discovery of mine is not new at all.)

I like it, and I like having these little pamphlets floating all around the house. It’s not perfect. The print can be small and scaling it up doesn’t always do what I want it to. And to my chagrin, it seems to print more easily and with cleaner margins from the phone.

A work in progress.

But while it may not be perfect, it really does work well. They’re far preferable to more screen time, especially since they contain no distractions beyond the words on the paper. Once printed, they will never require a battery charge or software update — or software at all. I’m pretty sure all those studies out there say that paper-reading is (you might want to sit down for this) better for your comprehension. I’m sure, too, that it’s a better activity to be observed in by watching eyes. And it’s just all around more enjoyable.

The process is also frictiony (which is, I think, a much better and stickier word than “frictional”). It (re)introduces physical checkpoints and limitations, even simple pauses, all of which keep you in the physical world, and all of which the “phone” is designed to help you avoid. I might send a dozen articles to the Instapaper app to (probably not) read later. I’ll send two or three to the printer to (almost certainly) read later, if for no other reason than that I will physically stumble upon them somewhere. Or I might not send any to the printer and just forget about it and move on. Which means that instead of being driven by FOMO to binge on a hundred articles with only a fraction of my cloud-y (heh) attention, I might actually start sitting down with something I really do want to read and doing it with all of my attention.

And it’s just so very nice to lose any and all concern for the gosh darn screen.

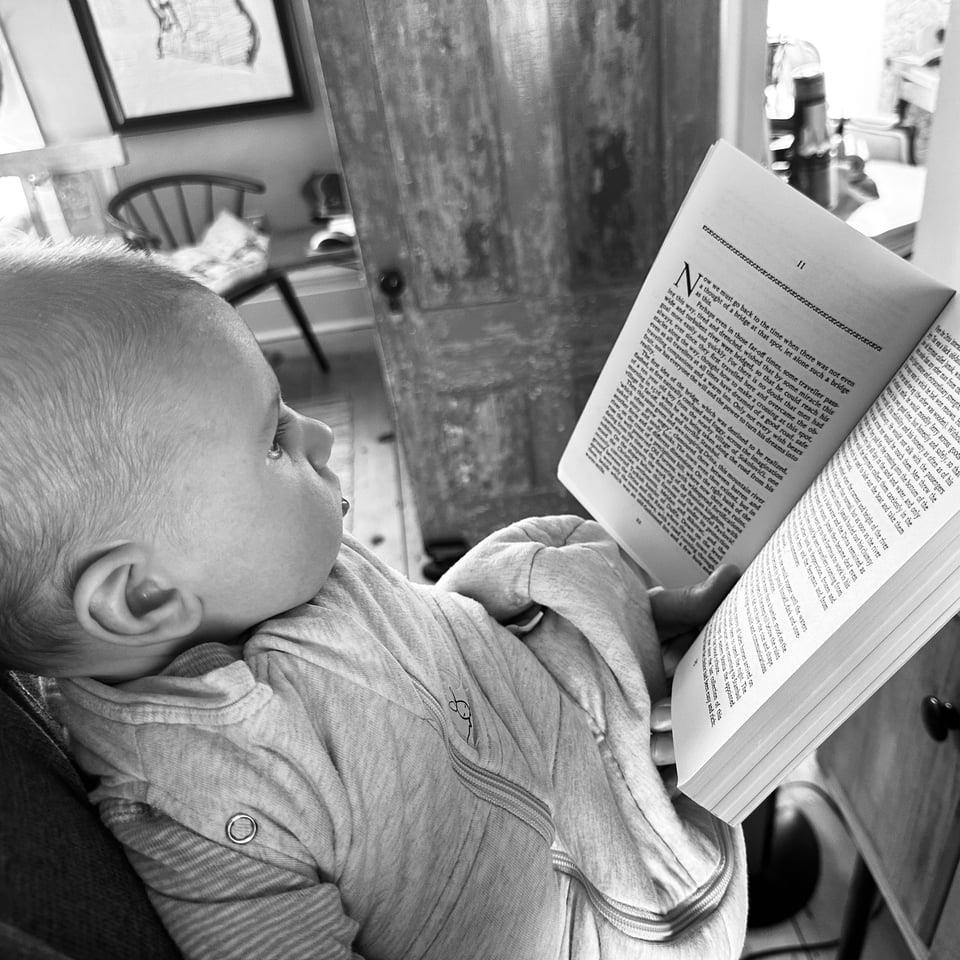

No Dick and Jane for this little guy; even at 11 weeks he went straight for Nobel Prize-winning Yugoslav historical fiction. 🤓

Possibly I began writing as a refuge from our insulting first grade text book. Come, Jane, come. Look, Dick, look. Were there ever duller people in the world? You had to tell them to look at things? Why weren’t they looking to begin with?

—Naomi Shihab Nye

Why, indeed?

One answer is dependency. As Shoshana Zuboff outlines so well and so shockingly in her book Surveillance Capitalism, dependency is the now-reigning feature of tech devices in our lives.

Our dependency is at the heart of the commercial surveillance project, in which our felt needs for effective life vie against the inclination to resist its bold incursions. This conflict produces a psychic numbing that inures us to the realities of being tracked, parsed, mined, and modified. It disposes us to rationalize the situation in resigned cynicism, create excuses that operate like defense mechanisms … or find other ways to stick our heads in the sand, choosing ignorance out of frustration and helplessness.

Our felt needs for effective life vie against the inclination to resist being tracked, mined, and modified by a commercial enterprise.

By “effective life” here, she means something like “going with the flow” rather than making trouble for yourself. But that’s not what I imagine when I hear the phrase “effective life,” and reading it in this moment, the sentence seems set up to concede an inevitably lost battle. So I want to save the word “life” here and spin it around: Our felt needs for genuinely effective, as well as affective, embodied lives vie against the inclination to go with the flow.

And man, am I vying.

Presumably, at some point along the road to “psychic numbing,” the choice of ignorance disappears, at least from view. But until it does, frustration and helplessness seem pretty inescapable. This is the perpetual state of things, a constant, nagging background noise — though still occasionally a front-and-center reality begging not to be ignored, begging to be dealt with.

Matthew Crawford says something similar in his book Why We Drive when he talks about one of many normalized situations that “presupposes your willingness to suspend those capacities and dispositions that form the basis for self-respect. Such resignation only feels like defeat for a little while, until the numbness sets in.” Think everything from the DMV to automated help centers to the (ahem) willing submission to the collection and distribution of near-infinite amounts of personal data through our own devices, done solely for giant corporate profit-through-manipulation, and all for the very small and easily affordable price of our human capacities for attention and care.

I digress. But we all know what Zuboff et al. are talking about, even if we haven’t read the books or prefer not to think about it. The “exit costs” from this ever-present, ever-silent drumbeat — costs in time, in effort, in a willingness to annoy almost everyone around you — are only getting higher. (How high those costs actually are in the grand scheme of things is, I think, debatable, possibly even laughable. But still, the difficulty of getting ourselves past them is very real.)

If you are like me, if you know this and refuse to be blinded or numbed to it, and if you are still having trouble taking the exit and eating the costs, still can’t quite find a way to live with these “devices” and to live peaceably with your own goals and your own conscience — well then, the only thing that can happen is that you become angry, or depressed, or perpetually annoyed at all the things you can’t do anything about. The only thing more exhausting than the Big Tech, Big Data, nudge, nudge, nudge world we’re living in is to feel that you are forever and ever only a week or two away from doing something about it, now and indelibly just a short time away from making those changes and getting back to what matters.

(I swear, I don’t think I am ever more than 3 to 5 seconds away from my inner Samir Nagheenanajar. Just watching that clip is cathartic.)

(And honestly, you simply cannot read Wendell Berry, let alone admire him for the agrarian god of simplicity that he is, and have a smart phone and not feel this constant disturbance in The Force.)

So to say I’m “putting my money where my mouth is” is to say that I need to either make the necessary changes with Tech in my life or just stop talking about it and let the numbness set in. If I believe (as I do believe) that I should at least minimize my (let’s face it) almost entirely lazy use of a company like Google; and that the buying and possessing of physical recordings of whole albums is better for me, my family, and the musicians and artists themselves, along with the entire experience and effect of music writ large; and that I should spend most of my life without a smart phone in my pocket let alone in my hand — then I should probably start eating more of my own dogfood.

And throughout the year, I’ll let you know how the monkey mind is doing.

Honestly, though, all those descriptions are probably themselves the result of the monkey mind. If there is a broader, better description of what I’m after, I borrow it from Kay Ryan.

In a short 2000 essay in The Ruminator Review (wonderfully collected by Christian Wiman with some of her other prose in the book Synthesizing Gravity), Ryan gives us a simple word to describe something we are in desperate need of: derichment.

The word came to her in a fairly obvious way. There is a lot of enrichment, and desire for enrichment, in the world, almost all of which smacks of greed and hubris, speed and distraction. We need the opposite of that, Ryan thought to herself; we need derichment. But rather than attempt to define what she means, Ryan offers just a few examples of the “faces of derichment” seen “in practice, not in theory.”

She speaks of a teacher, Ms. Foley, who, unable to stomach the “brutalization” of Emily Dickinson’s poetry two semesters in a row, opts to temporarily cut her from the class curriculum. “Ms. Foley had a private life of the mind that she protected, and to which she was eager to return.”

As a student, says Ryan, this enticed her, in a way that no classroom could have, to go to the library and find Emily for herself. This is derichment.

Here we see the carrot method of instruction at its least impure. The student was not offered a carrot; at most we might attempt to purify ourselves to the point that we might be worthy of being in the same room with a carrot.

Another face of derichment is Ryan’s mother, who, in the 1970s, having inherited $60,000 from an aunt, bought a slightly larger television for her mobile home and traded her used car in for a slightly newer used car. When asked later what else she bought with the money, her mother says, “Oh, I tried canned salmon, but to tell you the truth I like tuna just as much.”

Not surprisingly, her mother had also proven immune to fancier meals at the Basque restaurant. “You know,” she would say, “I could have just filled up on beans.”

Tested by wealth, tested by variety, my mother’s pleasures remained her pleasures. It was not as though she was a shrunken-up person without the capacity for pleasure; she had liked things very well right along—things like tuna and beans. And when presented with other delicious choices, she still liked tuna and beans. It is pleasant to think of a person like that, who genuinely likes what she has. It is also pleasant for a person to be so predictable, to say the same thing over and over as she did. There are ways in which pleasures become deeper when they are repeated. This is bedrock derichment stuff.

Our too-common experience of the Grand Canyon provides another example for Ryan, via negativa. She offers a very sympathetic description of the way we try to capture in photographs a “quantity of canyon” too big even for the human chest, so that “the too-great will not be lost.”

We have many such methods of convincing ourselves that we have embraced things that in truth defy us. We have big libraries of photographs and videotapes that we hope are holding onto things until we can get back to them.

There are one or two others, but the last one that Ryan mentions is the French artist Henri Matisse, whose love for the two forms of art he is most remembered for, painting and collage, were each discovered while being restricted to bed, first as a young boy with appendicitis and again later in life after abdominal surgery in his 70s.

“It is the vacuum created by being denied his usual occupations,” says Ryan, “that allowed Matisse the discovery of his deepest self.”

Which brings us right up to what I think is derichment’s most frictiony face:

It can be a good thing, then, to feel trapped, cut off, at your wit’s end, bored silly, left out, tricked, drained. We need to hear that gurgle when the straw probes futilely for more Coke. We need to be deriched.

[Jack’s note: We also need more walks, more snacks, and more belly rubs.]

Here are a few things that are worth your time:

Something I want to come back to in more detail, and that you might have noticed in the pamphlet image above, is Peco and Ruth Gaskovski’s recent newsletter on training for high fidelity in the world of “Post-meh-dernity”. I don’t know why I haven’t read more of their stuff.

There is a beautiful power in a committed no. When we rule out one course of action, two things happen. One is that certain doors are shut, locked, the keys dropped in the ocean. The other is that we activate our energies around an alternative pathway. To say no is not simply to deny something, not just an absence and dead end, but a moment of mental combustion that can explode energy into a new direction. A committed no is the launch pad for a committed yes.

J. Daniel Sims’s Plough essay “A Lion in Phnom Penh” is one of the most fascinating and eye-opening things I’ve read in a long time.

And there we were, elated at the victorious eviction of the lion from our neighbor’s yard as our own landlord used our rent checks to enforce the displacement of villagers forty miles north.

Book recommendation: Every once in a while, you come across a book that says — subtly, humbly, even unintentionally — this is what writing is for. Chad Holley’s short novel Shield the Joyous is one such book.

Leah Libresco Sargeant’s incredibly well researched and well reported piece in the newly launched Commonplace is a vital one: “Abortion is not and cannot be seen as the solution to the way we fail vulnerable pregnant women.” In her Substack newsletter, she adds:

This is a piece I hope can connect across the abortion divide. You can disagree with me on whether abortion is morally licit, whether it kills a child, but I hope you can agree that vulnerable women can’t be told that abortion is their primary defense against our discriminatory medical system.

My hope is that pro-choice and pro-life advocates have some shared ground where we can press for better care and clearer consequences for doctors who fail their patients.

The Commonweal podcast interview with Mark Lilla on his new book Ignorance and Bliss: On Wanting Not to Know is so very good, and excellently put together with musical interludes along with excerpts from the book read by the author (who sounds like Malcolm Gladwell’s doppelgänger). I haven’t yet, but I’m very tempted to pick up the book.

I mentioned in an off-the-cuff post after the election that Democrats needed to have their hearing checked. Along those lines, Mana Afsari’s piece for The Point, Last Boys at the Beginning of History, is excellent. Whatever heart she hears with and voice she writes with is a wonderful improvement on whatever it is I had in mind. Because you can really and truly hear what someone has to say without needing to agree with anything that they say; and — sadly and more commonly — you can disagree with everything someone says without ever hearing them at all. I admit that I have my doubts about how representative the people Afsari has met actually are, but I have no doubts about her genuine ability to hear those people.

Related to everything above, I wrote about Spotify, Simone Weil and Attention. I mentioned there that we have 98.9 WCLZ playing in the house for much of any given day, and that reminded me of something I intended to share last year: Jon Ward’s “Builders” interview with Matt Murphy, the general manager of WERU Maine (89.9), who started as a volunteer at the radio station in 1993.

You could hear and feel the community coming over the airwaves and I wanted to be in on that.

Here is Richard Wilbur’s poem “Driftwood,” which, it should go without saying, rewards multiple readings:

Driftwood

In greenwoods once these relics must have known

A rapt, gradual growing,

That are cast here like slag of the old

Engine of grief;Must have affirmed in annual increase

Their close selves, knowing

Their own nature only, and that

Bringing to leaf.Say, for the seven cities or a war

Their solitude was taken,

They into masts shaven, or milled into

Oar and plank;Afterward sailing long and to lost ends,

By groundless water shaken,

Well they availed their vessels till they

Smashed or sank.Then on the great generality of waters

Floated their singleness,

And in all that deep subsumption they were

Never dissolved;But shaped and flowingly fretted by the waves

Ever surpassing stress,

With the gnarled swerve and tangle of tides

Finely involved.Brought in the end where breakers dump and slew

On the glass verge of the land,

Silver they rang to the stones when the sea

Flung them and turned.Curious crowns and scepters they look to me

Here on the gold sand,

Warped, wry, but having the beauty of

Excellence earnedIn a time of continual dry abdications

And of damp complicities,

They are fit to be taken for signs, these emblems

Royally sane,Which have ridden to homeless wreck, and long revolved

In the lathe of all the seas,

But have saved in spite of it all their dense

Ingenerate grain.