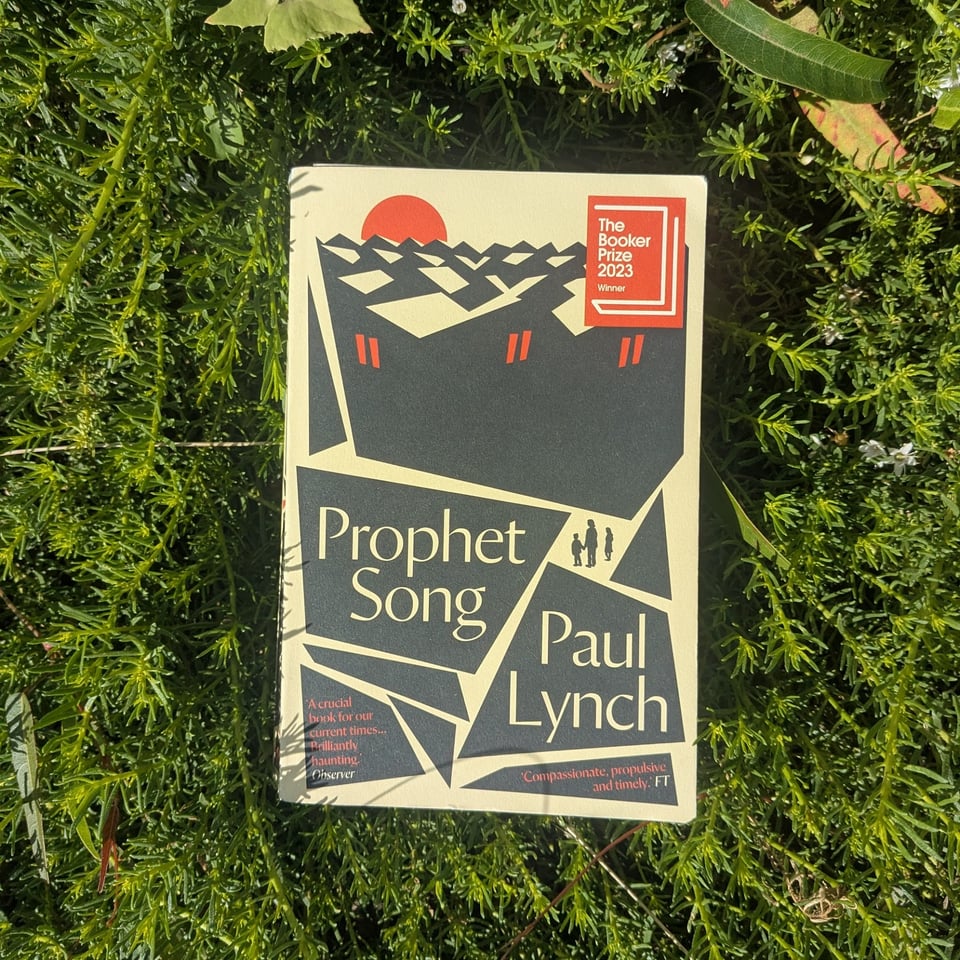

Prophet Song — Paul Lynch

2025-04-25

In December 2023, Antoinette Lattouf, a casual broadcaster with Australia’s ABC radio network, was fired from her short contract for re-posting a post from the Human Rights Watch account about the Israeli military using starvation as a weapon of war in Gaza on her personal Instagram account.

Although other ABC journalists regularly post on their social media on other topics, including Roe v Wade, Australia Day, and the Uluru Statement, Lattouf was fired for posting this singular post and portraying the ABC as “biased”. ABC argued in court that Lattouf was not fired but “relieved of work”. This was later found to be inaccurate.

It is alleged that there was pressure to remove Lattouf from the start of her employment, even before her Instagram post, as her political views on Gaza were considered problematic. A group of lawyers lobbying for the Israeli government sent a sustained campaign of emails to the ABC leadership encouraging them to let Lattouf go. (Lattouf was only employed for five days in total, and the ABC has now spent more than a $1.1 million AUD defending the case in court for 14 months). We are still waiting on a verdict on the case.

In 2024, a classical pianist giving a recital with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra prefaced a piece he was about to play with some comments about the work. Written by Connor D’Netto, the piece was called Witness.

Jayson Gillham, the pianist, introduced it with these words:

“Over the last 10 months, Israel has killed more than one hundred Palestinian journalists. A number of these have been targeted assassinations of prominent journalists as they were travelling in marked press vehicles or wearing their press jackets. The killing of journalists is a war crime in international law, and it is done in an effort to prevent the documentation and broadcasting of war crimes to the world.

In addition to the role of journalists who bear witness, the word Witness in Arabic is Shaheed, which also means Martyr.”

Gillham had simply introduced the piece by sharing the meaning of the work as it was designed by the composer. The institution deemed this so offensive and inappropriate, they ensured he would not be able to say it again to another audience.

In March this year, with the Trump administration spun up to full effect, Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in America arrested Mahmoud Khalil, who has now been effectively disappeared. With a valid green card and a university education, Khalil had been an organizer of pro-Palestine protests at Columbia University.

Organizing, participating in and supporting public protests has long been an important part of a functioning democracy. Being anti-genocide should ostensibly be unilaterally supported across the political spectrum; and yet Khalil has either been deported, imprisoned or murdered at this point — we have no idea where he is at all.

Khalil’s role in the protest was primarily in negotiating with the university, seeking divestment from the university. Although there was encampment and demonstration, Khalil’s involvement was in the boardroom. Before he was arrested, he was subject to vicious doxxing and bullying online, from university staff and other affiliates. He wrote this:

“I haven’t been able to sleep, fearing that ICE or a dangerous individual might come to my home,” the email read. “I urgently need legal support, and I urge you to intervene and provide the necessary protections to prevent further harm.”

On Truth Social, the social media network Trump created for himself after being removed from Twitter by its previous moderation group prior to Musk’s takeover, Trump wrote:

“This is the first arrest of many to come.”

These three events occurred at vastly different scales over the last year. Meanwhile, some enormous number of Gazan civilians have been murdered, with some estimates are as high as 70,000 which still may be lower than the reality, as the extensive nature of the bombing has led to thousands being trapped under the rubble. The broad breakdown of infrastructure makes official medical records objectively difficult to collate.

In addition to the shockingly widespread bombardment of the region, the blocking of supplies and aid has induced a famine. This is a war crime. Those who do not die of starvation risk dying from their injuries (more than 100,000 are known to be injured) due to the targeting of hospitals in the region.

The genocide in Gaza and the election of Trump are two threads of a terrifying resurgence of the authoritarian right all around the world. In Europe, we are seeing actual Neo-Nazi parties develop shockingly powerful influence. In 2025. In America, it is now illegal or partly illegal to get an abortion in 19 states. 19 states!

It is in light of these facts that reading Prophet Song this year felt chillingly… familiar. The book follows a woman living in the Republic of Ireland, Eilish Stack, whose husband is a union leader at the school where he teaches. He goes to a protest he is involved in as political unrest develops around the country. The protest is dispelled by force and he is arrested. He is never seen again, and our protagonist is left with her four children as the unrest develops into a violent civil war.

Many of the criticisms of this book, which won the Booker prize in 2023, is that the events of the book are a bit boring. We follow Eilish as she gets groceries, as she chats to her neighbors, and as she visits and checks in on her aging father. She takes a long time — arguably way, way too long — to accept that the far right party that has taken oppressive control of her country is there to stay. She believes that the uprising and local militias will be able to stand down shortly as the world rights itself and the international community inevitably intervenes and restores justice. It becomes increasingly frustrating following Eilish, reading about the everyday decisions she makes as if the world is peaceful and the conflict is simply a blip.

The prose is unusual but compelling; long sentences evoking James Joyce rush past your eyes a little faster than your imagination. Reality refuses to wait for you to catch up. There is a palpable feeling of unstable pace; everything happens unbearably sluggishly and shockingly quickly at the same time.

Over the course of the book, Eilish’s mundane world disintegrates into panic. Her eldest son, barely 17, is called up for military services by the state. He instead joins a local militia and goes into hiding. Her daughter is wracked by anxiety. Her father, struggling with dementia and the loss of his wife some years ago, swings from worrying confusion to shocking lucidity, and is desperate for Eilish and her family to leave the country before things inevitably get even worse. Her youngest son is injured with shrapnel in a climactic progression of the conflict to literally outside her suburban house on the street.

I was reminded by the Walking Dead spin-off Fear The Walking Dead, which tells the story of the zombie apocalypse from a different angle to the original series. A family goes about their normal tasks and outings while sirens start ringing more often in the background, while news reports seem to gradually sound alarming and groceries seem harder to get. Unless you’re really paying attention, it’s not clear that the zombie apocalypse has started. And isn’t that exactly how it goes?

I remember at the start of COVID for us in Melbourne, there was a period of time where it felt like I was watching the news and following Twitter with a twitchy paranoia; I eventually set up a call at the company I was working at to suggest we send everyone home and hunker down. The other leaders were skeptical and thought we’d be locked down for three months or so — it ended up being closer to three years. But for others less anxious than me it was something that weird internet people were simply overreacting to — my own parents had to be talked out of their planned Japan trip multiple weeks into the first lockdown.

Crises don’t always happen as suddenly and dramatically as you might expect, and they happen more suddenly to some than to others. In fiction, dramatic irony puts us in a position where we can see the wave crashing before characters do, which creates a horrific sense of unease. In reality, fascism is unevenly distributed, too; you don’t realize you have avoided the boot on your neck until you see it on your neighbour’s.

And of course, sometimes you’re not meant to notice. Late-stage capitalism thrives on the enslavement of our time and attention. Fascist regimes work best if they are sort of slipped on like a subtle perfume; ideally if the people don’t notice, it’s much easier to get away with. If we’re all too busy working our long hours and doomscrolling and keeping up with the latest culture war and at each others’ throats that’s good for them; it means we don’t have the chance to form class solidarity and fight back.

It’s definitely possible that you hadn’t noticed the incidents I outlined at the top, or that they hadn’t resonated with you as indicators of something more alarming. Eilish too spends most of the book in some sort of denial, believing that the world can’t be so unjust, and that if it is, it can only be an aberration; that people are fundamentally good and right and rational and kind, and that someone, some force, will come to help. It takes almost the worst possible thing to happen to snap her out of it, and by then, well, it’s far too late.

I was also reminded of Alex Garland’s searing Civil War, which reaches into a possible near future, following the plight of a small group of journalists navigating the American Civil War. The film serves to bring the kind of conflict we typically only see happening in non-Western countries firmly into familiar territory.

While war is an almost constant, it happens in the Middle East or in Asia or in Africa, where it can be easily filed away under “bad things happening to other people”. Lynch’s decision to set this in the Republic of Ireland serves to emphasise the fact that war is hell, and should it happen to you, you too would be in hell. It’s not as impossible as you might think.

Like Margaret Atwood, Paul Lynch knows that the shock is that it’s happening to white people, not that it’s happening at all; we ignore horrors at this scale and worse every day as long as they’re happening to other countries. Perhaps Ireland or America or Australia aren’t going to descend into civil war tomorrow, but the question is worth asking yourself: what would you do?

Would you leave? Fight? Pretend it’s not happening?

Would you keep mowing the lawn? For how long?

Would you stay in your house, even if you knew it could be bombed?

Would you send your child to safety even if it meant you had to stay?

These are questions that real people are asking themselves today. Saja, a young woman who has escaped Gaza, is looking to raise some money get to Ireland to finish her studies. Her family has been devastated and her studies have been interrupted. She has been accepted into Trinity College, which is wonderful, but unfortunately missed the cutoff for a refugee scholarship.

The Irish have strongly supported Palestine for some time. No stranger to conflict, and in particular, the occupation of colonial forces. Irish and Lebanese peacekeepers have worked together for so long in Southern Lebanon that many of the Lebanese have picked up Irish accents.

If you can spare anything at all, we’re trying to help Saja make it out of Cairo as soon as we can, as it’s not particularly safe for refugees there right now. I’ve chatted with Saja; she is a sweet, kind young woman who simply wants to find a way to live. She barely knew how to raise this money; I helped encourage her to set up the link, and she is working with We Are Not Numbers, who are finding ways to help other young refugees from Gaza find a way to continue on.

I hope I never have to escape a war zone. I hope you never have to either. Prophet Song is a stressful, dark read, but deeply relevant and a warning we should all be listening to. Pay attention as the sirens grow louder. Find ways to support your community. I hope you can help Saja. I hope you are safe. I hope this never happens to you.

Stray links and tidbits:

Aaron Bastani (Fully Automated Luxury Communism) attempts to interview (but mainly just listens to) Slavoj Žižek talk agout tariffs, ageing, forced subjectivity and just so many other things on his podcast Downstream

Black Mirror season seven’s Eulogy and Common People are worth watching

Documentary film-maker Lauren Greenfield’s series Social Studies follows a group of teens from LA with access to their phones, examining the impact of social media and unmoderated internet access on young minds

PJ Vogt interviews Greenfield about the show on his podcast Search Engine

Yannis Philippakis, lead singer from FOALS, has a new project with Tony Allen called Yannis and the Yaw

I’m very happy for this little girl and her sinistral seashell discovery

This essay interrogating the concept of libido as an oppressive misogynistic unscientific concept

The best take on Anora I’ve read so far (I didn’t love the film; I do love the essay)

I’m making Spotify playlists so you don’t have to listen to algorithmically made ones; here’s the latest

Saja’s fundraiser

Conor D’Netto’s album Witness.

Don't miss what's next. Subscribe to Tiny Rebellions:

Add a comment: