Underfueled and Overtrained: Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport

A deep dive into the invisible condition that affects 30-80% of elite athletes.

Even though track practice ended at 7:45, Harlowe Brummet-Dunn wasn’t finished running just yet. She couldn’t take time to stop and chat with her coaches or friends, or to take a leisurely stroll back to her dorm. Instead, she quickly gathered her things in the evening twilight and started her last race of the night: the race against the clock to make it up the hill to the dining hall before it closed at 8.

Student athletes don’t have their own dining hall at Princeton, and if Harlowe didn’t manage to grab food during this 15 minute window, she’d have to resign herself to the greasy ready-made burgers provided as late meals. She didn’t want that, especially not the night before a competition.

Lack of access to food is one of the key causes of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport, or REDs, which affects 30-80% of elite athletes, depending on the sport. The condition is “a syndrome of impaired physiological and psychological function,” says Dr. Margo Mountjoy, a clinician scientist and sports medicine doctor at McMaster University, “caused by exposure of that athlete to prolonged and severe low energy availability.” Basically, REDs is the result of a substantial mismatch between how much energy goes in and out of your body throughout the day. We take in energy by eating food, and expend it in all manner of ways, “with our heart beating, our hair growing, digesting our food, walking around for the day.”

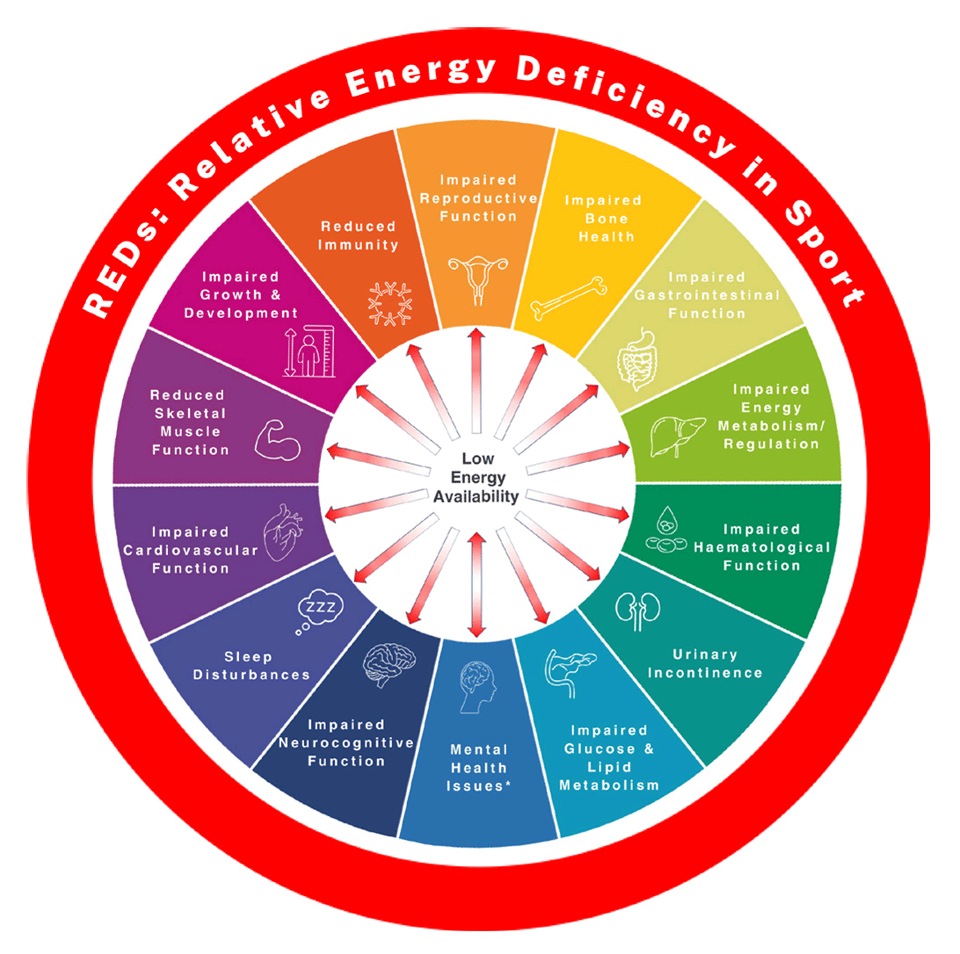

REDs used to be called the Female Athlete Triad, a name that connected three common symptoms in elite women athletes: disordered eating, loss of menstruation, and bone density loss. In 2014, the International Olympic Committee asked Dr. Mountjoy to lead a group of experts in reviewing the evidence and produce an updated Consensus Statement. They found that the Female Athlete Triad didn’t just affect females, didn’t just affect athletes, and that there were far more than three bodily systems involved. In the end, the more inclusive name Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport stuck.

With updated review papers in 2018 and 2023, the state of understanding of REDs has advanced rapidly. What started as a triangle graphic ballooned into a many-sliced circle of symptoms, including bone health and reproductive function, yes, but also gastrointestinal, metabolical, immunological, musculoskeletal, neurocognitive, urinary, sleep, growth, and mental health effects. When the body is consistently operating at a loss, it has to prioritize its most vital functions, like keeping your heart pumping and your blood clean, and so other systems need to shut down or operate at much lower levels.

But just because you’re surviving with REDs doesn’t mean you’re not doing permanent damage. A recent study from the University of Alberta found that participants with a prior REDs diagnosis had three and a half times higher odds of premature labor, and two and a half times the risk of preterm delivery as compared to the general population. As Dr. Mountjoy says, “This is a serious concern, not like strep throat, [where] you take penicillin and you’re better in a week. This is something that can have long-term repercussions.”

Another major change in the conceptualization of REDs is its causes. Whereas the Female Athlete Triad limited its scope to disordered eating, REDs recognizes alternative causes as well, such as ignorance and lack of access to food. Many athletes simply don’t know how much energy they’re spending and struggle to keep up with it. “At the very high level of energy expenditure, appetite is not a good indicator of how much you need to eat,” Dr. Mountjoy says. Especially when an athlete is not a professional with a team of experts around them or has other responsibilities like school and work, it can be very easy to underfuel. Harlowe knew this and tried to keep herself fed, bringing a stash of protein bars, fruit, and sandwiches to her meets to snack on throughout the day. But with the daily grind of her full course load in addition to her training, it was hard to keep up. She had access to nutritionists through Princeton’s athletic program, but didn’t find their advice all that helpful.

“It was like, ‘oh, you have to eat so many calories in a day.’ How am I even going to have time to do all that?” Harlowe said, “They want you to eat every two hours. Honestly, we’re so busy. It [Princeton] wasn’t really an athletic school, it was academics first, so all of us athletes really had to put athletic health on the back end.”

Financial barriers that block access to high quality and quantity foods can also play a significant role in REDs. Princeton sometimes provided meals when the team was travelling, something like chicken and rice or the hotel breakfast buffet, Harlowe recalled, but in other cases, the athletes were simply given $15 to spend at Whole Foods to buy their own meal. It goes without saying that $15 does not get you very far in a Whole Foods these days. This put athletes in a tricky situation. “Either you don’t get anything, because you can’t afford it,” she said, “or you’re spending a lot of your own money.” She would easily spend $80 on snacks, protein drinks, and fruit, but watched some of her teammates leave empty-handed so that they could buy Popeyes later on and get more bang for their buck.

These two causes of REDs are pretty straightforward to treat after diagnosis since they are overwhelmingly unintentional. American athletic trainers, coaches, and dietitians surveyed by Veronica Szygalowicz unanimously affirmed that “many of their athletes were misinformed or unaware of their nutritional needs.” They said that much of the misinformation came from nutrition advice on social media, or from trying to reverse engineer a diet from the “snapshots of a successful athlete’s life” that they see online.

But those brief glimpses at elite athletes can be misleading. Dr. Mountjoy describes how she works with athletes at the Olympic level to decrease their body fat percentage right before a competition: “We can periodize their body composition down to an ideal performance, and then they will perform faster. But then we bring them up again.” Here is where the problem comes in.

“Young athletes see the older, more mature Olympic athletes doing this body composition periodization,” she says, “not realizing that in fact that person is only in that state of having lost a little weight just for the Olympic Games, and the rest of the time when they're training, they're up at a higher weight or higher body composition. And these young people think, ‘I just want to look like that Olympian all the time.’ And then they're in trouble.” That desire for slimness, clinically called a drive for thinness, is the final main cause of REDs.

While the prevalent image of eating disorders often depicts a waifish young woman striving to lose weight to achieve a certain look, this is only one small slice of the disordered eating spectrum. People of all genders, ages, and weights can exhibit disordered eating, often completely unrelated to their appearance. Individuals with Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) struggle to eat enough because of reasons like sensory issues, executive dysfunction, or low appetite, while Orthorexia limits intake on the basis of excessively strict rules about healthiness.

In elite athletes, their drive for thinness is sometimes based on the idea that weight loss can improve their performance.

Bodies, Proportions, and Advantages

Different body weights, sizes, shapes, and proportions give advantages and disadvantages in different sports. For example, most professional basketball players are extremely tall because in a sport where the aim is to put the ball into a 10 foot tall hoop, additional height is directly beneficial. But the biomechanical advantages and disadvantages can get much more specific than that. UC Davis professor of molecular exercise physiology Keith Baar explains that long legs may be advantageous for a runner, but only when paired with small feet. The location of added weight, at the end of the ankle as opposed to on the torso, can drastically affect energy consumption. An added weight of 4 pounds on a runner’s waist only increases energy usage by 3.7%, while adding it to the foot adds 20%. Large feet, Baar says, are “not a good phenotype for running, but if you’re a swimmer, you want to have huge feet, because now you’ve got flippers.”

Body shape and proportions are generally considered to be ‘stable inequalities,’ traits that differ between people that they cannot change like biological sex and age. These stand in contrast to ‘dynamic inequalities’ like strength, speed, endurance, technique, and strategy, which can all be improved through training and coaching. Body weight is a bit trickier to categorize.

Irena Martinkova, associate professor at Charles University in Prague, notes that body size “seems to be the most unstable of what are supposed to be the stable person-dependent characteristics,” in that it is "manipulable to a certain extent.” And if a trait is manipulable, athletes will try to use it to their advantage. She describes how rapid weight loss techniques, considered relatively safe under supervision and with effective rehydration techniques, can produce a temporary 3% loss in body mass, similar to the body composition periodization strategies Dr. Mountjoy uses with her Olympic-level athletes.

Some scholars break down the differing prevalence of REDs across different sports, anywhere from 30-80%, as a range from low- to high-risk. Sports that require acrobatic skills like gymnastics and diving, anti-gravitational sports like ski jumping and climbing, and endurance sports all favor low body weights. These are the high-risk sports which receive the most attention and study.

But Martinkova disagrees with the simplicity of this scale. Instead, she suggests a different model that identifies specific risk groups across all types of sports. Besides lean sports, she proposes two other categories of sports rules that can incentivize weight management.

First, sports that advantage lean, robust muscularity. These sports generally focus more on explosiveness and power over endurance, and include most ball sports, downhill skiing, and sprinting. In general, muscle is more desirable than fat in these arenas, but extra fat is not all that problematic. Traditionally, these sports are considered low-risk for REDs, but some athletes within these sports, like those in a very competitive sport that are looking for an extra edge, or athletes whose training is disturbed by injury and struggle adjust their caloric intake accordingly, can still be incentivized to strictly manage their weight.

Martinkova’s final category is sports with weight-prescribing rules like weight classes or limits. The weight management incentives of weight limit sports that set a maximum weight, like lightweight rowing or skeleton, or a minimum as in equestrian, are clear, especially for people who do not naturally fit within the requirements.

But at first glance, it seems counterintuitive that weight classes could do the same, since the classes should allow people of many different weights to compete on a relatively equal playing field, right?

In most weight class sports, you want to be high within your category since you want to pack in as much muscle as possible. This often leads athletes to weight cycling, where they train at a “normal” weight and then cut down just enough before a competition to make their preferred weight class. Sometimes this can be done healthily under medical supervision, like Dr. Mountjoy and Martinkova discussed. But often, athletes take this process into their own hands and can do themselves serious harm.

Monica Nelson is a doctoral candidate at the University of Waikato and an Olympic Weightlifter that has competed on the national level since 2014. As is standard in the sport, she bulked and trained until a competition approached, when she’d starve and dehydrate herself in order to make her weight class. Though her baseline weight was only a couple kilos below one weight class, she felt she “had not ‘filled out’” that higher category based on her “lack of visible abs,” and felt she had better chances competing in a lower weight class. Wanting to avoid the strain of cutting again after a particularly grueling cycle, she tried to keep her weight down permanently. She chronicled the intense surveillance she put herself under, obsessively tracking everything she ate. Her lifts approached her all-time bests, but she was constantly hungry and exhausted, getting lightheaded even on short walks. In the competition that would qualify her for Nationals, she tore a ligament in her elbow. Only then did Nelson decide to move up a weight class.

If the process of repeated weight loss during training is so harrowing, why do the athletes keep putting themselves through it? Anyone who’s involved with sports probably thinks that’s a stupid question. In order to even get to the level of the modern-day professional athlete, you have to be able to enjoy the pain, at least a little. And if it isn’t full-blown masochism, they at the very least derive a deeply significant sense of value and fulfillment from pushing their bodies to higher and higher feats.

When I was a competitive dancer in a pre-professional program, I would rub ice directly on my knees, in the softer bit below the cap, but above the point where my shinbone emerged, until the pain, both from the extreme cold and from my tendonitis, faded into numbness. I did this almost every day just so that I could keep dancing. Then dancing would aggravate my tendons all over again. The chronic tendonitis in my knees never went away until I was forced to stop dancing during the pandemic.

Sports sociologists Robert Hughes and Jay Coakley coined the term “sport ethic” to explain these kinds of behaviors. The sport ethic is the value system that defines who is a “real athlete.” It’s made up of a tapestry of norms and practices that vary depending on the sport and the specific sporting community, but generally includes themes of being dedicated and striving for distinction within the structure of your sport, all while facing adversity, overcoming challenges, making sacrifices of your time and energy, being willing to give up traditional growing-up experiences, and playing through pain, all for the love of the game. Sometimes people’s personal investment traces back to the goal of winning championships or the hope of making money, financing your education through sports. But even without all that, “there is an identity and moral worth to be established and reaffirmed, and a connection to a coach and a group of teammates to be honored. These are powerful motives.”

While these norms can be very useful to justify pushing yourself to your full potential, build and strengthen bonds, and establish a team identity, and they certainly can be healthy, Hughes and Coakley point out that there can be real danger in overcommitting to these norms. They call this “positive deviance,” defined as “an unqualified acceptance of and unquestioned commitment to” the sports ethic that can lead people to “do harmful things to themselves and perhaps others while motivated by a sense of duty or honor.”

Harlowe remembers how her cross-country team tracked their runs on an app for everyone else on the team to see. Whenever you or your teammates went on a run, everyone could see how fast they were, and could compare themselves to each other. It wasn’t just a personal recordkeeping tool, she says. “I think that kind of competition and that kind of tracking of each other was more of a pressure to be the best and probably be the healthiest in kind of an unhealthy way.”

REDs is particularly common in endurance athletes like long-distance runners. Hughes and Coakley cite findings that these athletes show obsessive or “addiction-like” behaviors similar to those in anorexic patients. Perfectionism and compulsive exercising, two traits easily amplified by the quantification and comparison these apps engender, are both psychological risk factors for developing REDs.

The simple love of the sport is only one explanation for the sport ethic. The other is rooted in the relatively new phenomenon of the professional athlete, the highly paid superstar, the Olympian with endorsement deals, or, to be a bit more realistic, a way to get a college education without a mountain of debt. When Harlowe, who had been bouncing around different sports for years, suddenly placed third in the state in a fourth grade track competition, “It became a huge part of my life because I was good at it.” She joined a club team “because you can't really get that good if you're just doing it through the school system,” with the express goal of making it to the college level. “It was kind of the end all be all,” she says, “the dream that they sold us.”

Athletic success can be a life-changing tool of social mobility. But the body is fallible, one bad injury can completely wipe out your chances, and pushing yourself too hard might come back to bite you in the long run.

Sports injuries might just be bad luck, but it’s also very possible that they can be at least partially caused by REDs. Besides the physical and mental health consequences, REDs also negatively affects sports performance in a number of ways: Athletes have higher risks of injury, slower healing times and recovery from training, decreased responses to that training, and worse cognitive skills, muscular strength, endurance, power, and motivation. These all add up to lesser performances. The IOC’s 2023 update paper rounded up study results showing that when suffering from REDs, endurance athletes, bodybuilders, and cross country skiers’ muscle strength decreased, runners and rowers’ endurance was worse, and swimmers, judo athletes, and road cyclists’ power output was weaker.

So even though some sports do advantage a lighter body weight, the bodily and mental impacts of REDs on performance, clearly outweigh the marginal boost gained from the weight loss. Underfueling is not the rational choice. Aside from ignorance and lack of access, why do athletes do it?

Societal Biases Toward Thinness

After Nelson’s devastating experience trying to maintain her competition weight, she partnered with Shannon Jette to conduct an ethnographic study looking into why weightlifters choose to go through such painful and dangerous processes rather than competing in the weight class that best fits their natural weight. One participant described detailed regimens she’d use to cut almost 10% of her bodyweight, calling her use of Epsom salt baths to lose last-minute water weight “PTSD City,” and saying that she still felt tempted to cut even more weight without telling her coach. But when she was asked about moving up a weight class or staying at a weight higher than her baseline, she declined, saying that “her body felt slow and her pull-ups felt difficult.” Even though the physical consequences of weight gain were much milder than those of weight loss, weightlifters still found the suffering of cutting preferable to the ‘slow’ feeling of heaviness.

Here, Nelson and Jette theorize, is where societal biases about weight and fatness come into play. All their participants agreed in principle to the sentiment “Mass Moves Mass,” which means “not only that a wide variety of body fat percentages could be considered athletic, but that body fat had an abstract, positive relationship to strength gain.” This idea is backed up by the science, since hypertrophy, the process of muscle growth, “cannot be effectively accomplished without simultaneous gains in fat mass, particularly in trained populations.” The weightlifters surveyed applied this view to other Olympic weightlifters and various other athletes, but rarely to themselves.

In describing their own bodies and training strategies, the participants instead held the view Nelson and Jette call “Muscle Moves Mass.” This approach holds that only muscle mass contributes to strength, and that any body fat is “fluff” and “inefficient.” The weightlifters cyclically bulked and cut, both to make weight and to lose the fat that came with their gains. Doing anything else was seen as “nearly unimaginable,” even after poor performances, plateaus and repeated injuries.

There’s an interesting disconnect here. The weightlifters understand the scientifically backed understanding of fat as it pertains to lifting, but are unable to apply it to themselves, instead defaulting to antifat rhetoric. Nelson and Jette, quoting Patricia Vertinsky, conceptualize this dissonance as “social values packaged in a scientific wrapping.”

The discourse around sport, especially at the elite level, all purports to be extremely evidence-based and rational. Athletes and coaches invest in the highest-tech training strategies, supplements, and recovery methods in hopes of optimizing their bodies, and therefore their performances. But just because something seems objective or scientific doesn’t mean that it is. After all, it wasn’t that long ago that race science was an accepted part of the academic ecosystem.

In elite sport, it can be hard to untangle when weight management techniques are based on athletic advantage, and when they are a symptom of an antifat society. And to complicate things even further, sometimes strict weight management instills further biases even when it is an effective strategy.

Gwen Chapman studied a women’s lightweight rowing team’s journey to making weight. The team began dieting in April to prepare for their weigh-in in August. As they upped their training program, they ate less, restricting their fat intake. Some of them went on additional “fat-burning runs” on top of their training so that their food restriction could be less intense. The process was a whole-team affair, with teammates frequently talking about food, eating together, and surveilling each other to keep each other in line. After all, if you didn’t lose enough weight, you weren’t just failing yourself, you were letting down the whole team. Chapman writes,

“One rower told of a time when she felt full at ‘the wrong time to be full,’ broke out into a sweat, and felt ‘totally guilty,’ like she had been caught doing something that was ‘totally wrong.’ She responded by trying unsuccessfully to make herself vomit, even though she knew that this, too, was ‘wrong.’”

But despite the harrowing and “mentally detrimental” nature of their diet and training, the athletes felt good about themselves and their bodies. They got attention when they went out to the bar, they looked fit, toned, strong, and skinny, and they bonded with their teammates. While they had thought that the shape and weight of their bodies before training was just the way they were, that thought seemed “pretty bogus” now, since they knew they “could just change that and have a completely flat stomach.”

After the season ended, they stopped training and dieting. Of course, they regained the weight, and were back where they’d started by the beginning of the next season. But they felt differently about their bodies now. When they looked in the mirror, they saw a body that was “fat,” “gross,” or “dumpy.”

“Having discovered that the idealized body image was attainable,” Chapman explains, “they found it difficult to regain their previous sense of satisfaction with their ‘normal’ bodies.”

Even beyond the short-term mental and physical effects of cutting weight, and the possible long-term health impacts, this new sense of dissatisfaction with their baseline bodies demonstrates how weight stigma can creep into our psyches. For women especially, thinness is societally associated with fitness and athleticism.

“I think of myself as fairly athletic,” one of the rowers said during the off-season, “but I don’t think I look like an athlete anymore.”

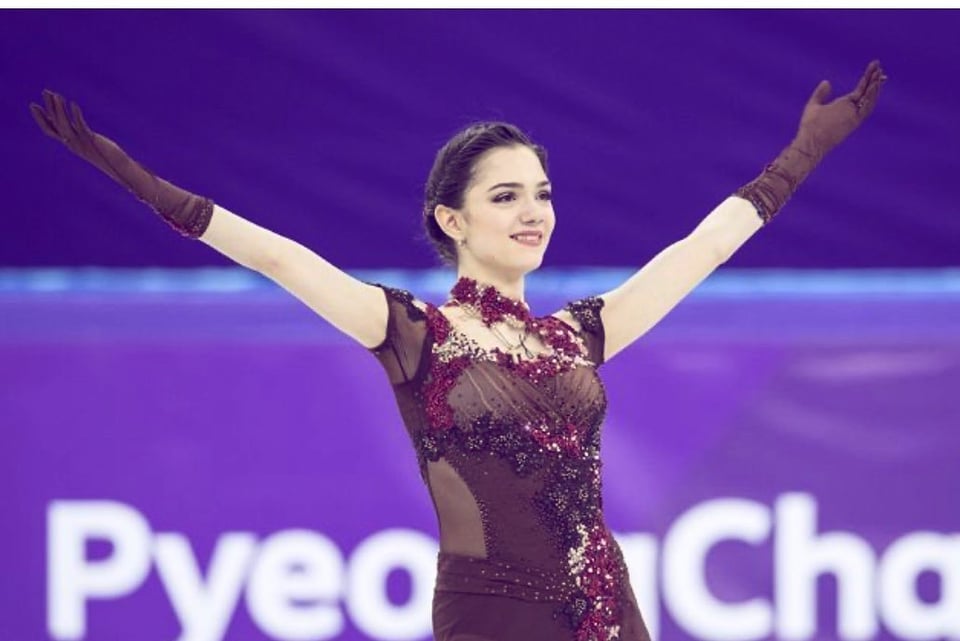

Having the right look is desirable, even if, as in rowing, it doesn’t help you perform better, and is just a byproduct of qualifying to compete. But what if it does in another sport? Aesthetic sports like figure skating, gymnastics, and various kinds of dance are all scored, at least partially, based on how the athlete looks while performing. And whenever judges rule on a question of artistic merit, their biases will inevitably influence their scoring. Combining this pressure with their acrobatic nature, it’s not surprising that both REDs and eating disorders are extremely common throughout aesthetic sports.

Evgenia Medvedeva, Russian Olympic silver medalist figure skater and 2018 Olympic favorite, first went to see a nutritionist back around 2016 or 2017. She wanted to get better control of her body weight, stop the yo-yoing. But after she gained three kilograms, she left. Next, she tried a dietician who responded to a description of her daily meals with, “That’s very little.”

Evgenia then said, “Thank you, goodbye. I didn’t come here for that: I came here to figure out how to lose weight down to the bone.” She had already concluded after the nutritionist that “maybe women’s figure skating isn’t about health after all.”

During her Olympic season of 2017-2018, Evgenia trained and sometimes even competed on a stress fractured ankle. After her silver medal performance, she learned that she also had three fractures in her lower spine and very advanced osteoporosis. In an appearance on the Russian show Katok, she tells the whole story, how her doctors told her, “These are bones we normally see in 85-year-old grandmothers. We only inject this treatment for grandmothers, but for you, we’ll do it because you need to continue living somehow.”

Evgenia is not the only figure skater to go to extreme lengths to maintain the lowest possible body weight. In fact, her coach at the time, Eteri Tutberidze, is notorious for reports of her athletes undergoing public daily weigh-ins, liquid supplement diets, not being allowed water during competition, and even taking hormones to stop the change of weight distribution during puberty. Most of her skaters, just like Evgenia, retire still in their teens due to injuries (often broken bones), eating disorders, or a combination of the two.

It’s not possible to diagnose Evgenia based on online information, Dr. Mountjoy says, especially because REDs is an exclusionary diagnosis, meaning that doctors must run tests to rule out every other potential cause for the symptoms. But Evgenia’s disordered eating, bone density loss, and her acknowledgement that “everything regarding my health as a woman only began to stabilize after the Olympics,” all raise red flags as the indicators of the original Female Athlete Triad.

As opposed to figure skating, sprinting incentivizes muscle growth more than body fat restriction. And Harlowe, as a relatively short sprinter, was always more worried about being too skinny and needing to put more muscle on than being too fat. But that doesn’t mean she didn’t hear plenty of rhetoric about the danger of putting on too much weight. Harlowe’s coaches consistently warned the young girls about the butter phase: “That’s what they call gaining weight through puberty.”

Harlowe remembers them saying, “A lot of girls are fast before the butter phase, and then you’re going to slow down.” She worried about it throughout high school, watching other older girls get their body fat percentages tested and being told to lose weight, and breathing a sigh of relief when the dreaded butter phase seemed to pass her by. Even in a sport whose format doesn’t incentivize thinness, fat was still demonized.

Is there any sport where fat isn’t seen as harmful?

University of Leeds professor Karen Throsby studied marathon swimmers in a paper called “You can’t be too vain to gain if you want to swim the Channel: Marathon swimming and the construction of heroic fatness.” Marathon swimming is done in open water at distances of more than 10 kilometers. The English Channel, almost 34 kilometers wide at its narrowest point, takes marathon swimmers an average of 13 hours to cross, an arduous and frigid journey at any time of year.

What sets marathon swimming apart from most other sports is that as part of their training, athletes often need to gain weight in order to insulate their bodies from the cold of open water, making them less vulnerable to hypothermia. Unlike other sports that merely tolerate fat as adding power in combination with muscle, marathon swimmers specifically need fat to keep them safe.

Throsby joined a group that trained together frequently and took note of how they talked about their bodies, and their newly acquired fat. The first thing she noticed is that it was framed as temporary, as fake. The fat on their stomachs wasn’t really a part of them, but a “necessary act of bodily discipline and sacrifice in the service of the swimming endeavor.” This is what Throsby calls “heroic fatness.” One swimmer said that the fat was “okay because it is not who I am.” The assumed ability to lose the weight again after the Channel swim was clear.

Along with this mindset came jokes, mostly made by the men in the group, about their fat as almost a separate creature from themselves. Throsby wrote that men “domesticate their fat stomachs, rendering the fat almost pet-like.” They squished it to make it look like a mouth, saying, “Feed me!” or, “It’s time to feed Norman,” the name one of the swimmers had given to his fat. They saw themselves seen as tougher and nobler than those using “wimpsuits” as opposed to “bioprene.” They also disparaged fat non-swimmers, seeing their own fat as symbolically different since it was in the service of athletic achievement. A self-identified fat swimmer watching the physical comedy said, “It makes you wonder what they must think of me.”

Women in the group seemed to experience their fat differently. They didn’t joke or banter about it, and when they did talk about it, it was located within their complex life-long relationships with weight, diet, and exercise. But the euphemisms they used were still telling. Throsby found women swimmers talked about their fat cloaked in metaphors of criminality. “A pending swim serv[ed] as an ‘alibi’ or a ‘get out of jail free card’ for fatness,” she wrote. The underlying guilt these women felt for gaining weight, just as it was amplified by sporting rules and mores for the lightweight rowers, was in this case alleviated by them.

REDs is such a complex topic because weight management itself is so fraught. We can’t talk about the drive for thinness in sport purely as a rational choice made by athletes to gain a competitive advantage because weight and fatness on their own are not value-neutral in our society. While in some sports, low body weight is advantageous, in others, that proposed advantage is little more than “social values packaged in a scientific wrapping.”

In the circumstances when gaining weight is clearly athletically advantageous, the athletes Throsby studied needed to use mental workarounds to justify it to themselves, like as getting away with a crime or as heroically suffering in service of athletic achievement. The positive social reinforcement you can get from temporary weight loss, as the lightweight rowers showed, can substantially change your body image during the off-season, potentially leading to a desire to maintain that weight loss more permanently. Perceiving yourself as “dumpy” or “fat” whenever you don’t fit beneath the lightweight limit has nothing to do with athletic prowess. It’s a manifestation of societal biases toward thinness.

What can we do to try and prevent REDs?

First off, “Let's celebrate the amazing performances that people have, not how big they are or fat they are,” Dr. Mountjoy says, “No one wins a medal for their body shape. So let's focus on the medal and the performance, not on body shape.” As athletes have become celebrities, sportswriting and tabloids, which have a long history of loudly discussing the un/attractiveness of different bodies, have grown uncomfortably close to each other. When women began to enter elite sports, major news coverage was largely written by men, many of whom did not take women’s athleticism seriously. Nowadays, when mainstream coverage is somewhat more restrained, semi-anonymous internet commentary has eagerly risen up to take its place.

But Dr. Mountjoy sees another use for the media: “Spread the word on the risks and consequences,” she says, “Some of these health consequences I mentioned cannot be reversed.” Remember that entirely removed from weight stigma or perceived performance boosts, simple ignorance and lack of access to food are two of the key causes of REDs. While awareness has been on the rise within sports medicine circles, most people outside of these circles don’t know about REDs at all. Nobody I told about this project while working on it had ever heard of REDs before, even those who were athletes training and performing at high levels. It’s great that professional athletes who can afford a team of experts around them will be taken care of, but the many still in the pipeline who will never even make it that far are not. They might be doing irreversible harm to their bodies in the service of their team, their coach, an athletic ideal, or just free college and the hope of a more prosperous future. And they don’t even know it.

Athletes also have an important role to play in helping to prevent REDs. The IOC found that peer-to-peer educational interventions around REDs were very promising, and Dr. Mountjoy agrees that they can help by being “advocates and ambassadors for healthy living.” Through the sport ethic, teammates are tightly bonded together and can be highly influential in shaping each others’ perceptions of what “correct” food and weight management practices are. King’s College London lecturer Oli Williams’ study on eating discourses among elite athletes found that some athletes showed an intentional resistance to restrictive dietary practices. Some of his interview subjects even mentioned performatively eating “bad” foods in public to show their more timid teammates that it’s okay. Williams calls this an “immunity” to the virtuistic pressures of elite sport, where many athletes feel they need to demonstrate their goodness not only through their athletic performance, but also by excelling in following the social and behavioral rules of their team.

One prominent example of this kind of “immunity” through public advocacy is the social media content of US rugby star Iloha Maher. In an Instagram Reel in July, Maher said, “‘Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels,’” flexing in a sports bra while quoting the adage popularized by supermodel Kate Moss, “Uh, [have] y’all tried being strong? I feel good. I feel well fed. I feel ready to take on anybody.” Maher’s muscular build goes against feminine standards of petite and lithe athleticism, and her outspokenness around her pride in her body, eating enough to keep herself fueled through her training, and criticizing tools like the BMI, have made her a great role model for the fight against REDs.

Public advocates are especially important because compliance from athletes, coaches, and families is one of the most important factors in treating REDs. If an athlete is surrounded by voices saying “‘The doctor doesn't know what they're talking about. Come on, let's do some work,’” Dr. Mountjoy explains, “they're going to trust the coach, not the doctor.” Having role models that offer dissenting points of view from the unfortunate norms of nutritional neglect or excessive caloric restriction is hugely important to motivate athletes to seek and follow through with treatment. Former REDs patients are especially valuable in this respect, since Mountjoy finds that athletes tend to listen to and trust their fellow athletes’ experiences.

All of these strategies rest on individual action, which is all well and good and can make a significant difference. But this problem is not just individual, it’s systemic. As long as athletes remain unsupported and uneducated about their nutrition, the rules of sport incentivize weight loss, and the sport ethic compels athletes to do anything possible to get an advantage, some people will keep winding up with REDs.

Reflecting on the role of sporting organizations throughout her youth in terms of health and nutrition, Harlowe concludes, “Honestly, I don’t think they did that great of a job. I think if food and recovery was emphasized more for me as a kid, maybe I would have been a little bit more healthy.” Athletes build habits and routines in their childhoods, and even those who never make it to the professional level should be given the tools and resources they need to thrive, not just survive.

Dr. Mountjoy emphasizes the role of culture within sport, and the fact that sport organizations have a lot of power to shape that culture. Athletes, coaches, and judges should all be educated on athlete nutrition and encouraged to prioritize athlete health over results or aesthetics. And beyond that, “They can actually put in policies on correct management of body composition,” she says, “They can write policies to prevent coaches from weighing athletes in public on a daily basis and prevent coaches from inhibiting athletes from eating correct food.”

The rules of sport can incentivize unhealthy behavior, and therefore sport organizations hold some level of responsibility for these outcomes. And some sports federations have begun to change their regulations in response to wider awareness of REDs.

The IOC has fully phased out weight classes in rowing, with the final lightweight race taking place in Paris in 2024. And earlier that year, the International Federation of Sport Climbing announced that athletes will need to get a health certificate to show that they are not suffering from REDs before competing, with random follow-up testing throughout the season as well. The rules of sport are not ancient natural facts of life. We made them, and we can change them if they hurt people.

In some ways, REDs is a predictable outcome of some high-level sports. An obsessive drive to be the best at any cost consistently leads people down dangerous paths. But what else can we expect when there is so much to be gained, financially, socially, intrinsically, from reaching that upper echelon? If there is an advantage to be gained in a sport from a very specific body composition, athletes will try to get it. Some have the advantage of having someone like Dr. Mountjoy on their team to help them do it healthily. But others who try to reproduce the same effect on their own will end up hurting themselves. As Martinkova says, “A fair competitive advantage does not mean a morally acceptable, reasonable, and healthy advantage.”