The Authentic Sumo Experience

Sumo + Sushi's night of edutainment

After the final triumphant beat of the taiko drums stops ringing through the hangar-sized warehouse, an announcer draws the crowd’s attention to the other side of the room. A spotlight lands on Konishiki, a large man – though nowhere near as large as he was when he was the heaviest sumo wrestler of all time at 633 pounds – who sits on an elevated podium halfway between the ring in the center and the blacked out walls of the building. He picks up his microphone and greets the crowd, welcoming us to the Los Angeles stop of Sumo + Sushi.

The event, put on by Seattle-based SE Productions, has been touring the United States intermittently since 2019. It’s billed as ‘edutainment,’ an effort to introduce Americans to a highly localized sport that they likely would not be able to come across otherwise, at least in a live setting. “Before you leave tonight,” Konishiki’s voice booms over the loudspeaker, “I guarantee you’re going to enjoy sumo, you’re going to like sumo, you’re going to want to come to Japan to see a tournament.”

Konishiki himself straddles the line between the two cultures. Born in Hawaii, he was scouted on the beach at 18 years old, and took the offer to train in Japan knowing almost nothing about the sport. Despite his naivete, he shot upwards through the ranks of the Japanese Sumo Association (JSA), becoming the first foreign-born wrestler to reach ōzeki, (champion), the second highest rank in sumo behind yokozuna (grand champion). You may know him from Fast and Furious: Tokyo Drift. Konishiki remained in Japan even after he retired in 1997, crediting sumo with allowing him to learn the language and culture of the country. Now he uses his star power to help spread the love of his sport back in the country of his birth.

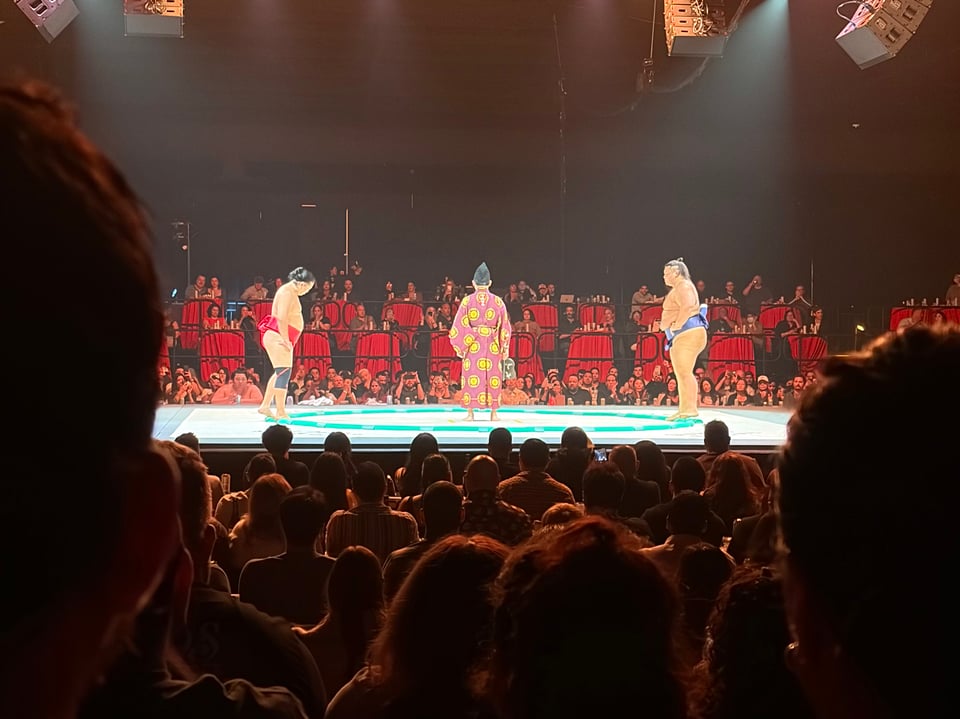

The night is broken up into three blocks. Block A begins with Konishiki introducing himself, then the five retired sumotori who would be wrestling for us that night. One by one, a spotlight follows them from one corner all the way until they climb the stairs to stand atop the central platform, a square within which the circular ring is inscribed. Konishiki rattles off their histories and accolades as classic rock tracks, Thunderstruck, Welcome to the Jungle, blare on underneath. On stage, they shed their robes to reveal their mawashi, a silken loincloth that Konishiki assures us “actually costs a lot of money.”

The sumotori, narrated and directed by Konishiki, show us a series of exercises they use for training. The wrestlers raise one leg high in the air for a few seconds and then bring it down with incredible force, an exercise used to train balance. “Underneath all that fat there’s a lot of muscle,” Konishiki says, “their lower backs are strong, they’re built like big ballerinas.” In another balletic parallel, sumo wrestlers have to be extremely flexible, so they demonstrate their middle splits. Konishiki tells a story about how he first gained his flexibility while the wrestlers mime along, wrenching the performatively inflexible wrestler’s legs apart as the heaviest sumotori sneaks up behind him to put his whole weight into pushing his torso into the stretch.

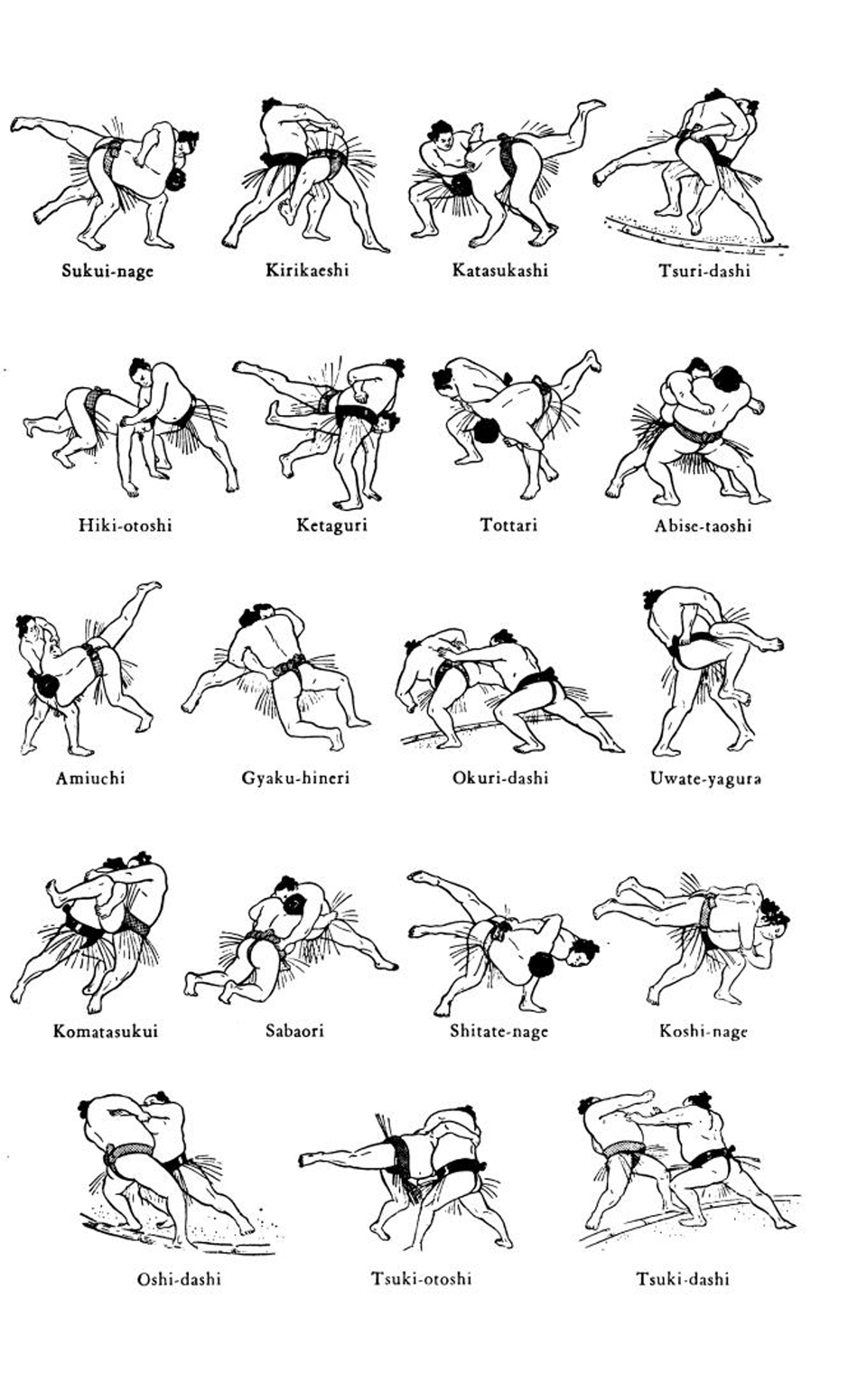

In block B, they teach us the techniques sumo wrestlers use in the ring. There are 84 different techniques in sumo, consisting of various throws, holds, or other miscellaneous strategies to either force your opponent to step outside of the ring or make some part of their body other than the soles of their feet touch the ground inside the ring. These are the two ways you can win a bout.

But not all techniques are right for every wrestler. In fact, “the majority of those techniques, someone like Saku or Yuji,” who come in around 275 pounds, “can do it better than I do.” Konishiki intones this as different pairs of wrestlers show off their skills, first at full speed, then more slowly, always reorienting themselves so that audience members on all four sides get a good view. About a thundering rush straight across the ring, Konishiki says, “This is something that I, or Ohtani, or Ruru,” two 400-pound wrestlers, “would do. But that is something that someone who is smaller would love to see us do because they can take advantage of the timing, either get down, get up, or get around him.”

This trade-off between the advantages and disadvantages of size is unique to sumo, the only combat sport in the world without a weight class system. After showing how a large wrestler could use a certain hold to pick a smaller wrestler up, then walk to the edge of the ring and simply drop him over the line, the same pairing resets to show how that same approach could end badly for the big guy. This time, the simulated bout ends with the bigger wrestler flipped over onto his back and the smaller one victorious.

“This is a technique that all you ladies can do to your husband when you go home,” Konishiki says, earning a chuckle from the crowd. It’s all about timing, and “feeling your opponent’s weight. You can feel if they’re leaning towards left or right, and you time it perfect so when you’re feeling him coming forward, you’re helping him go down.”

Next, the wrestlers demonstrate what not to do. A referee enters and Ruru spends the next few minutes ostentatiously breaking all the rules: pulling hair, hitting with closed fists, gouging eyes, kicking above the belt, trying to untie his opponent’s mawashi, all while absolutely terrorizing the referee. The crowd erupts in laughter as he chases them in circles around the ring.

In block C the audience finally gets to see the sumotori wrestle for real. After each bout, the loser swaps out and the victor stays to face another opponent. The first wrestler to win three in a row wins. The bouts are exciting, quick, and the crowd is on the edge of their seats. Our eventual champion of the night is Yuji, 6’1 and 275 lbs, who wears a silver mawashi. But the night isn’t over just yet.

The final spectacle of Sumo + Sushi is truly unique. If you buy one of the six available ‘Get In The Ring’ add-ons for your ticket, priced at $250, you have the opportunity to get in the ring yourself and test your wrestling prowess against the retired sumotori of your choosing. Most of the matches are comical. The crowd yells for the men coming up onto the stage to take their shirts off, which they each eventually do. The crowd yells for them to take more off, which they do not.

One man from the audience, with the helpful experience of Taekwondo as a kid, does actually get a win against one of the pros, shocking both the wrestlers and the audience. Four other young men slam themselves ineffectually against their opponents, who wait it out for a few beats, smirking out into the crowd, and then easily, almost gently, maneuver them out of the ring. One young woman steps up, and the wrestlers fall into a pantomime, each begging for her to choose them as her opponent. She officially gets a win against Meccha, though his comically exaggerated movements make it clear that he helped her along.

As we walked back to our car, I wondered about that finale. It felt like a very untraditional end to a night of learning about a very traditional sport. But how authentic, or how accurate to actual sumo practice, was what we’d seen that night?

The History of Sumo

Sumo: the Sport and the Tradition is an English-speaker’s guide to getting into sumo, written by S. A. Sargeant, sports editor of the Asahi Evening News in Tokyo in 1959. Sargeant was an Englishman who moved to Japan in the 1930s and taught English at the Imperial Naval Academy, among others. Though the book suffers from some period-typical racism (too much use of the word ‘oriental’ for my taste), it still presents an interesting comparison to Sumo + Sushi. Both of them, over half a century apart, are attempting to package and present sumo in a way that would appeal to foreigners.

Sargeant begins with the history of sumo, ranging from the completely unsubstantiated to the meticulously documented. Over two thousand years ago in the court of the Emperor Suijin, Taema-no-keyana triumphed over the 7’1 giant Nomi-no-Sukune by kicking him so precisely and forcefully that he killed him on the spot. This, Sargeant assures the reader, would be frowned upon nowadays. Sumo wrestling continued throughout the common era, with organized tournaments popping up either in temple compounds or imperial courts. The first ever yokozuna was crowned in the early 17th century during a tournament at the Kyoto imperial court. Akashi Shiga-no-suke was said to have been over 8 feet tall and weighed more than 400 pounds, though Sargeant freely admits that he is “shrouded in mystery” and that “there is actually no precise record available” to confirm any of the details.

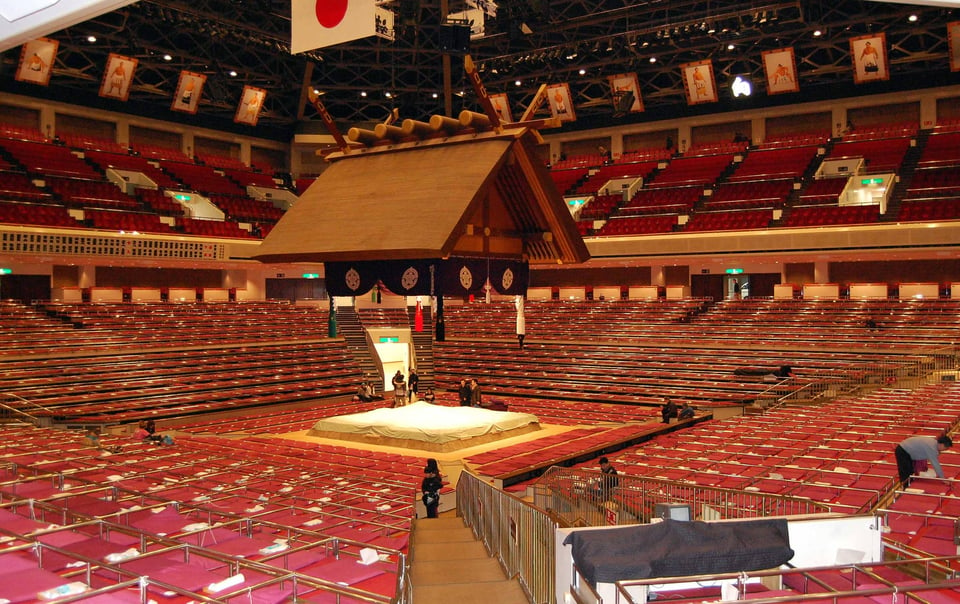

Sargeant describes sumo as a sport full of “pageantry and ceremony,” attributing this to its long and storied history and its origins as part of temple and courtly life. The entrance of the yokozuna, for example, is ritualized to a T. Every tournament day around 3:30, the wrestlers in the top makuuchi division walk in in single file, wearing elaborately embroidered aprons called kensho-mawashi. They stand in a circle around the ring, clap their hands in unison and, as one, adjust their aprons before leaving.

Then, first a referee, then an announcer, then an attendant, then the yokozuna, and finally his sword-bearer enter the arena. The yokozuna wears a massive white rope with zig-zag streamers attached around his hips. He goes through a set of movements in the center of the ring, clapping his hands and extending them diagonally in carefully choreographed movements. He raises a leg, balances with it at the peak of its height, and then thrusts it back down to meet the Earth. The sound echoes outward to even the farthest spectators. The crowd gasps and cheers. He finishes his routine, steps out of the ring, and bows.

Another ritualized element Sargeant describes is shikiri-naoshi, the pre-match ritual. The wrestlers stomp, toss handfuls of purifying salt into the ring, and squat down to stare at each other. This sequence might be repeated a number of times. The ritual has two main purposes. First, to try to get into your opponent’s head, figure out what they’re going to do when the bout starts, and psych them out. Second, to give the wrestlers enough time to amp themselves up to the proper level of intensity.

It’s unsurprising that Sumo + Sushi left these practices out. There weren’t any yokozuna present, though I would have loved to have seen the embroidered aprons, and the shikiri-naoshi takes up to four minutes each time. Despite it being “regarded as the very marrow of the art by those in the know and, indeed, by the wrestlers themselves,” Sargeant also describes shikiri-naoshi as the biggest “stumbling-block” in the way of foreigners trying to engage with sumo, since they lack “the patience of the Oriental.” He recommends that during shikiri-naoshi, you study the crowd and think about what brings so many different kinds of people together on this day to watch wrestling. Once it’s over, you’ve “cleared the hurdle” and “can sit back comfortably and begin to enjoy this time-honored art.”

Putting the racism aside for a moment (we’ll come back to it), Sargeant considers the key appeals of sumo to be in its long history of traditions and ritual, and in its cleanliness: spiritually, physically, and even in terms of sportsmanship. The historical basis of the traditions makes the ceremonial elements “seem not a whit out of place,” lending “a dignity to the proceedings which is surely one of the principal sources of its charm.” The cleanliness of the sport is embodied in the purifying salt, wrestlers frequently rinsing out their mouths, the ring being meticulously swept between matches, and the extreme sportsmanship and gentlemanly character of the wrestlers themselves. Though Sargeant says that the word “grotesque” might “be the first epithet to come to a Westerner’s mind after his first viewing of sumo,” he urges the foreign viewer to look a bit deeper. Beneath the surface, he says, you find a sport that embodies all the ideals of the western-style sportsman.

Isn’t it remarkable that this ancient tradition, Japan’s immaculately preserved national sport, is perfectly suited to western sporting paradigms?

Another History of Sumo

R. Kenji Tierney’s “From Popular Performance to National Sport: The ‘Nationalization’ of Sumo” traces sumo’s place in Japanese culture from the beginning of the Tokugawa period (around 1600) to the modern day. The version of sumo that emerged in the early 20th century is the one that we all know of, one that is directly symbolic of the nation of Japan, its history, and its culture. But under the rule of the Tokugawa Shogunate, sumo flourished in the city of Edo as a different, much more lowbrow mode of entertainment.

Completing the trifecta of Edo’s popular culture alongside geishas and kabuki theater, sumo wrestlers lived on the margins of a very stratified class system. Some performed independently on street corners, while others worked in troupes that held hereditary rights to tour and perform in certain areas, and others still were retained by daimyo, feudal lords, much like samurai were. Biannual commercial tournaments did already take place at this point, but in general, Tierney says, sumo was “less a sport than a spectacle.” The main attractions of many sumo matches were gimmicks, putting unusual-looking people in the ring for viewers to gawk at, like obese children or men with gigantism. Female wrestlers were also common at this time and hugely popular.

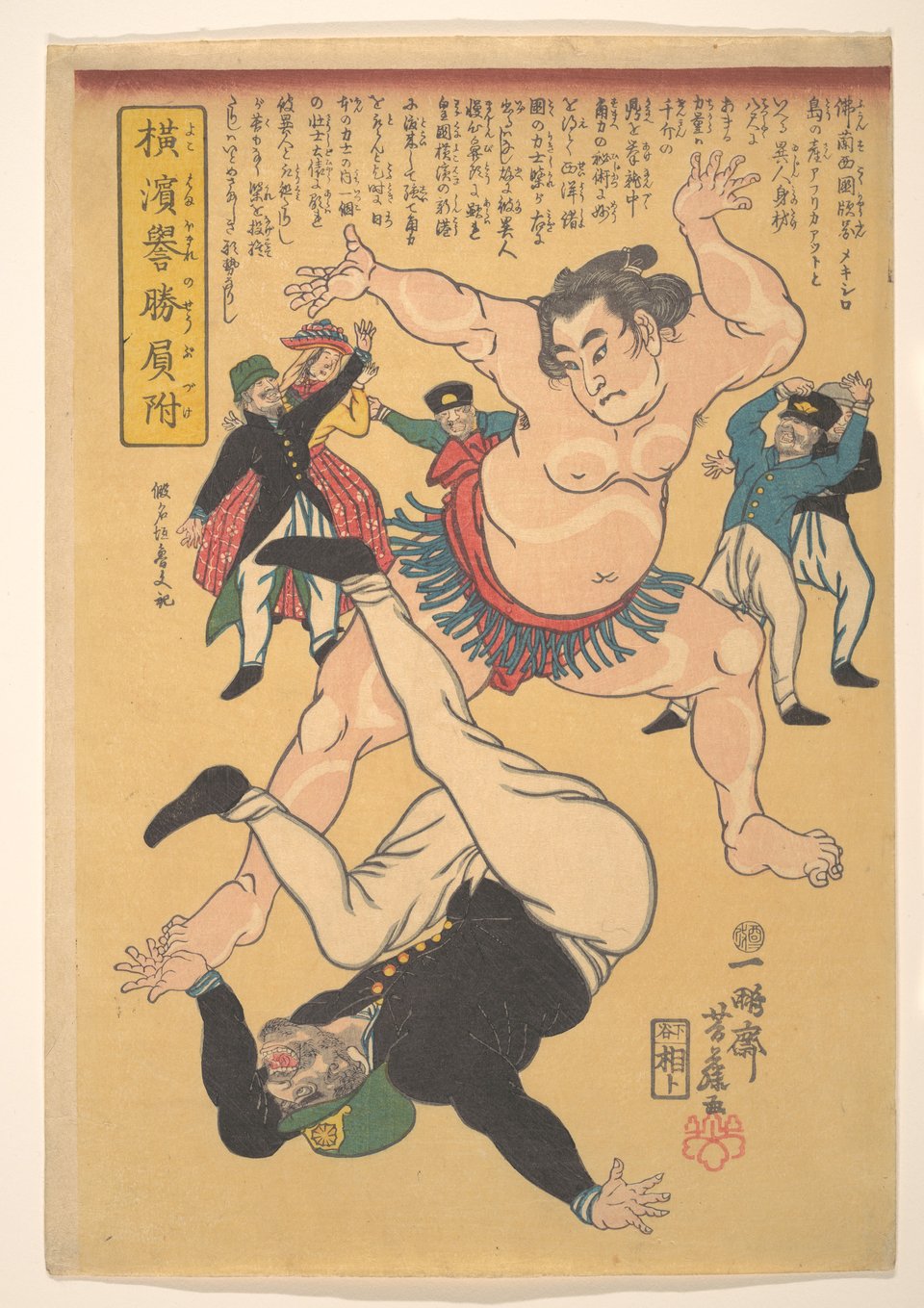

The first major shift in how sumo was perceived began with the arrival of Commodore Perry, the United States Navy man whose expedition ended Japan’s isolationism in 1854 with the Convention of Kanagawa. During his visit to Japan, he was shown a sumo exhibition and found it completely uncivilized and barbaric, expressing his disgust in his official report. The comments of Rutherford Alcock, Britain’s first minister to Japan, illustrate a similar sentiment:

“This so utterly confounds all our ideas of training, that I am at a loss to understand how such masses of flesh and fat can put out any great strength. They strip, and then, squatting opposite each other, look exceedingly like a couple of white-skinned bears or well-shaved baboons.”

Sumo did not fit the western visual perception of sport, which idealized a muscular, but thin physique. It also didn’t fit into the ideals of western sporting culture, still relatively new at the time, but already promoting its core tenets, including fairness, gamesmanship, formalized rule-sets and bureaucratic organizational systems.

As Japan westernized and modernized in the years following the Meiji Restoration, the tension between sumo and foreigners grew ever stronger. While part of the Japanese culture sided with the wrestlers (as illustrated above), other intellectuals absorbed western sporting ideology and mirrored it, many calling for sumo to be banned entirely. While everyone else was growing a trendy western-style moustache, sumo wrestlers refused. When an 1871 law outlawed the topknot and sumo wrestlers received an exception, they really found themselves as the odd ones out in their own country, a suddenly anachronistic relic of bygone years. The window of what was normal had shifted, and so “the wrestlers quickly came to embody a past too recent to be recalled positively.”

Western ideologies continued to spread in the 1880s. Body maintenance, nationalism, and eugenics were all the rage, encouraging citizens to improve their physiques, spirits, and minds in service of their country. With this came a reconsideration of what their country was and what it meant. Meiji intellectual Nitobe Inazo published Bushido (the way of the warrior) in 1899, in which he argued that the moral code of samurai was the moral base of Japanese culture much like Christianity for Europe. With the recent boom of judo, which blended physical combat with moral and spiritual teachings, why not try pulling these elements into sumo?

Sumo-do (the way of the wrestler) recontextualized sumo by emphasizing existing – or introducing new – ‘historic’ traditions rooted in spiritual virtue. An 1884 performance before the emperor that was advertised as an ‘ancient’ form of sumo was actually only thirty years old. Referees were given newly designed costumes in 1909 based on the Ashikaga family’s hunting outfits from the 14th century, and when the Kokugikan stadium was built, the ring in its center was built in the style of the 7th-century Horyu-ji temple in Nara. Neither of the sources of inspiration had all that much to do with sumo, but they recalled Japan’s ancient glories. Instead of being archaic remnants of an uncivilized and barbaric time, sumo became “the embodiment of a primordial Japanese spirit.”

Sumo’s transformation also went in the other direction, seeking legitimacy within the world of western sport. The practice of yaocho (matchfixing) was made taboo, individual winners of tournaments were now declared, and countless other small changes were introduced, including starting lines, time limits, and rematches. Spectators were no longer allowed to throw money or articles of clothing into the ring to show their admiration, and sumo wrestlers were required to be fully clothed when entering or exiting the arena.

The Kokugikan’s name translated to “national skill hall,” (“skill” in this context is now more commonly used to mean something like sport) tying sumo to the nationhood of the emerging Japanese Empire. When it was built in 1909, Japan was fresh off winning wars against the Chinese and the Russians and full of national and military pride. Sumo really leaned into it. Wrestlers frequently performed at military events, publicly led army drills in parks wearing custom made uniforms, and sumo was even made compulsory in schools and military training. Two military leaders served as chairmen of the JSA in the first half of the 20th century, and the organization even briefly shared its logo iconography – a cherry blossom and an anchor – with the navy. Sumo was so closely tied to the military that it was briefly banned after Japan’s surrender at the end of World War II. But before the collapse of the Empire, wrestlers frequently toured newly conquered territory, putting on exhibition matches across Korea, Manchuria, Taiwan, and the Pacific Islands.

The early 20th century was also when sumo wrestlers first started traveling farther, bringing sumo directly to the west. A yokozuna called Hitachiyama traveled to the United States in 1907, spending time in New York, Chicago, and Washington D.C. where he was “quite enthusiastically received by President Teddy Roosevelt.” The walking stick and top hat he wore on these trips is now in the Sumo Museum in Tokyo. He returned to America again in 1909 and yet again in 1915 when he attended the Pan-Pacific Exhibition in San Francisco. But Hitachiyama wasn’t the only one. In 1910 a wrestler named Oikari led a large group of sumotori to the Japanese-British Exhibition in London, then extended their stay after its end, toured across first Europe, then South America, where Oikari retired and eventually died. Yet another sumo, Tachiyama, brought sumo to Hawaii in 1914.

The sumo they were spreading across the world was already very close to the form of sumo that we see today: one that was at once heavily modified to fit western conceptions of sport, but also simultaneously emphasized its historical character and traditionalism. That’s what Sargeant saw in the 1950s and why he understood sumo the way that he did. If a foreign audience could get over the Japanese-ness of all the rituals and historical flourishes (read - their racist and fatphobic impulses), the underlying mechanics were perfectly legible as a serious and respectable sport.

The sumo of the Edo Period, on the other hand, was a form of popular entertainment, more concerned with satisfying a crowd and earning a livelihood than with concepts like sportsmanship, fairness, and bushido. But western colonial sporting culture did not recognize sumo as valuable in its own right, and as Japan westernized, sumo was discarded. Only by tying itself to key cultural concepts that were on the upswing at the beginning of the 20th century – national pride and militarism, sporting culture and body maintenance, bushido and tradition and the spiritual purity of ancient times – was sumo able to adapt and survive.

So, How Authentic is Sumo + Sushi?

In bringing sumo to the west, Sumo + Sushi has to navigate all of these dynamics, whether they like it or not. The wrestlers involved in the production are following in the footsteps of their predecessors, the first wave of sumotori that toured the world in the early 1900s. After the west had first glimpsed sumo in the 1850s and deemed it a disgusting and barbaric spectacle, the traveling wrestlers brought with them a new and much more palatable practice. As Sargeant explained, if foreigners could look past their instinctual prejudiced reactions, they really would find a rich sporting culture underneath.

The process of sumo’s transformation arguably culminated at the 1998 Nagano Olympics, as the first foreign-born yokozuna performed the ring-entering ceremony and sumo was provisionally recognized as an Olympic sport. Sumo’s evolution throughout the 19th and 20th centuries followed a path that has inexorably led it toward international legitimization.

Of course, that’s not to discount the value and meaningfulness of sumo’s historical and spiritual aspects. Sumo’s revamped sporting culture is just about as long-lived as tennis or football, and both of those sporting cultures aren’t made any less valid or real by the fact that a different kind of tennis or football existed beforehand. And the instinct toward global recognition is completely understandable. It’s only natural for athletes who dedicate their entire lives to sumo to want themselves and their sport to be taken seriously.

That’s what Konishiki wants, for sure. In an interview with the Tokyo Journal, he says, “That’s the sad thing about it. People only see what they joke about. That’s the reason I took this job. I saw the need for somebody to address the misconceptions about the sport. They make it look like it’s just big guys, and I couldn’t stand that.” Sumo wrestlers work incredibly hard, training five or six hours a day, full-time, with no off-season. Konishiki wants to demonstrate this to the audience in a visceral way, which is why he invites the six audience members to the stage.

“They get to go against these guys who’ve been doing the show for almost two hours and still have the stamina to continue,” he says, “They come away with the physical part and then the respect for each other in the ring.” The sumo lifestyle is hard, and he estimates that 80% of major league athletes in the US wouldn’t last a year under its rules and restrictions. “That’s how sumo is so different. Western minds usually can’t cope with that. Professional sports are more like a money-making thing,” he says, “but not in sumo.”

Here Konishiki hits on another foundational transformation of sporting culture, but this time not one coming from Japan. Led by commercialization and mass media, western sporting culture massively changed throughout the 20th century. The ideal of the gentleman amateur, spread across the globe and all the way to Japan, was a kind of spiritual and moral ideology that viewed athletic pursuit as a moral good in and of itself, and money as an evil corrupting force. But the financial invasion into the sporting world was inevitable, as capitalism always seems to be. In the end, the money won, sports mega-events are an entire sector of the entertainment industry, and athletes are brands.

Though there are some sponsors, brands, and patrons in sumo as well, they are fewer and smaller and their interactions with wrestlers are generally kept behind the scenes. Strict regulations limit how wrestlers can capitalize on their fame. “We don’t get paid even one one-hundredth of what other athletes get paid,” Konishiki says. In his post-sumo career, he has had to spell his name out in the Latin alphabet because the JSA prohibits any commercial use.

Despite Konishiki’s disdain for western-style commercialized sport, Sumo + Sushi clearly leans into some aspects of it in order to make sumo more accessible to the American spectator. Time consuming rituals that might scare the western viewer off are replaced with classic rock walk-in music and the wrestlers’ physical comedy, both of which draw from the tropes of WWE-style wrestling. It makes a lot of sense to introduce American audiences to sumo by framing it within the style of a more familiar form of wrestling.

But drawing upon American professional wrestling is also a bit of a risk, since the WWE is widely known as an entertainment product full of theatrical and pre-planned storylines, rather than a serious sport. Showing off sumo as an entertainment product might be an easy way for westerners to dip their toes in before jumping into the deep end, but it might also lead some people to assume that the kiddie pool is all the depth they need. This is only compounded by the fact that, even after over a century of time since the first Americans disrespected sumo, some westerners are, in fact, still racist.

As the wrestlers first walked up to the ring, the yelling started from the group sitting directly behind me. When Yuji, 6’1 and 275 lbs, entered the arena, they commented, “He’s not even that fat.” As Ohtani, 6’1 and 410 lbs, followed, they yelled, “Yeah, we want the big ones!” While the emcee explained different sumo techniques, the wrestlers performed a series of throws. One of the spectators behind us said, “That little guy’s getting thrown all over the ring! I don’t see how he’s ever going to win.” Her friend had to explain to her that they weren’t actually competing right now, only demonstrating. Once the tournament started, they were shocked when one of the smaller wrestlers was able to beat one of the bigger ones.

It was clear that these westerners weren’t interested in the edu- of the event, just the -tainment. Konishiki had carefully and repeatedly explained how size differences came with many advantages and disadvantages, and that every sumo technique came with a corresponding counter-technique. But the uneducated American’s perception of Sumo is watching fat, nearly naked Japanese men run into each other, and when faced with the fact that some of the wrestlers’ bodies weren’t as strange as they’d hoped, and that these smaller ones could actually beat the larger ones, these individuals were seemingly unable to reconsider their biases or absorb the new information.

In a lull between in-ring activities, one of the organizers asked the wrestlers, sitting ringside, about their favorite food they’d had in the US. One replied, “Pinks hot dogs,” a local LA institution. He spoke with an accent. The people sitting behind us burst out laughing. They exaggeratedly mimicked his accent, giggling. “Pink-suh hot-uh dog-uh,” they repeated over and over again.

I don’t think that most of the audience came in with as many preconceptions or as closed of hearts and ears as that group that sat behind us. My friends and I, at least, had a wonderful time learning about and watching sumo and were able to be normal about it. And despite endless hypotheticals, there’s truly no way to know whether another, more serious approach, would have yielded different results and gotten through to those outliers.

So as one last thing to think about, I propose this: By choosing to present sumo in a night of entertainment, as an event full of humor, as a spectacle where you can see men with remarkable bodies showcase their hard-won strength, flexibility, and technique, isn’t Sushi + Sumo in some strange way more authentic to Edo Period sumo than the tournaments you see today at the Kokugikan?

Beyond that, is it actually possible to have a truly authentic sumo experience? The ‘real’ sumo we see today isn’t ancient or primordial, but is itself a reaction to western pressures. As western sports have now shifted toward commercialism and spectacle, is sumo fated to eventually bend to these pressures? If sumo is to emerge as a sport onto the international stage as Konishiki hopes, saying he might be the one to form an international sumo league, will it first need to conform, once again, to the global image of sport?