You Are What You Eat

Casey Means, the Trump administration’s new nominee for Surgeon General of the United States, has a prescription for America. You can find it in her 2024 book, “Good Energy: The Surprising Connection Between Metabolism and Limitless Health.” In Means’ vision, “Good Energy” is a holistic approach to health, one predicated on the idea that “everything is connected.” The text strikes a tone that mirrors Means’ own career path, from training to be an ENT surgeon to life as a wellness influencer whose Instagram, @drcaseyskitchen, boasts nearly a million followers: there’s a sprinkling of grounded research that cites reputable medical journals, and a blizzard of plausible-sounding nonsense. (Means dropped out of her surgical residency and is not currently a licensed doctor.) Either way, what she offers is a kind of earthly paradise, one in which “you can enjoy balanced weight, a pain-free body, healthy skin, and a stable mood… the natural state of fertility that is your birthright.”

But like many other visions of paradise, to attain Means’ state of Good Energy, you have to obey the rules. And there are a lot of them.

According to her dubious statistics, only 6.8% of Americans are “optimizing energy production in their cells,” which is the prerequisite for the aforementioned earthly Eden of the body. For the other 93.2 percent, Means lays out a checklist of all that you must do to become one of the corporal elite. The section of her book on “Food” includes a daunting 23 items, starting with “I currently use a food journal or food tracker consistently to monitor what foods and beverages I'm consuming” and continues with eating three cups of leafy greens a day, plus avoiding foods with “refined seed oils,” all pastries, all sweetened drinks, all white flour, all artificial sweeteners, and—for a bonus—having the ability to not eat for longer than four hours without feeling “excess hunger or cravings.” There are further sections on “Toxins” (don’t store your food in plastic containers or eat high-mercury fish or use plastic water bottles or eat anything with artificial food dyes) and “Meal Timing and Habits.” Altogether, the material on food dwarfs the rest of the (very long) checklist, which includes sleep and the mind-body connection.

What it all amounts to is that Means’ “bold vision for health” in America involves an incredibly stressful, highly involved method of examining absolutely everything that goes into your body. It entails researching whatever you may consider eating, and avoiding oral contraceptives, antibiotics, and over-the-counter pain medications like ibuprofen, plus plastic water bottles and unfiltered water.

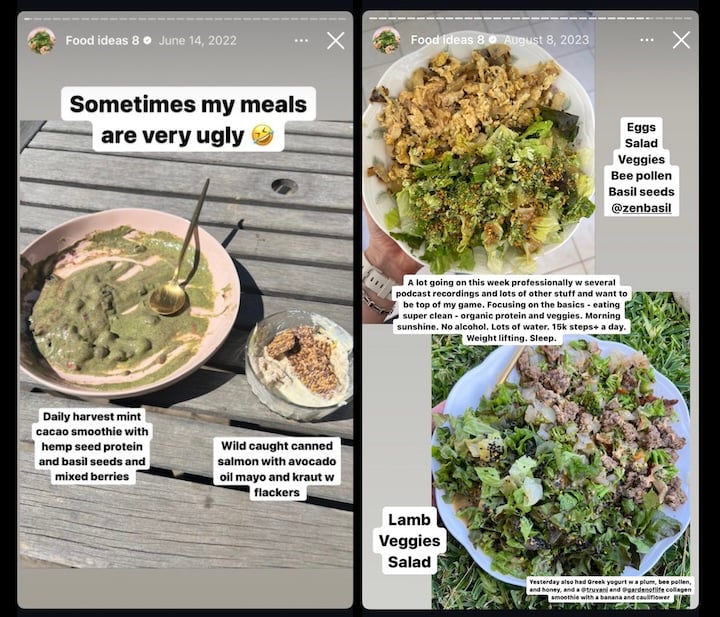

Fundamentally, what Means is arguing in her book—and through her Instagram feed, which is chock-full of some truly awful looking green goops and wedges of unidentifiable protein—is that, should you resist this long list of prescriptions to ensure your food is pure, you are creating your own Bad Energy. You are the source of this Bad Energy, and its solution, and suboptimal outcomes are, fundamentally, your responsibility. Only through an obsessive level of attentiveness can you avoid being a slovenly, depressed, pain-filled creature, enslaved to your decrepit body.

The irony, of course, is that Means and many others like her demand a different kind of enslavement to the body: under a hodgepodge of scientific and pseudoscientific principles, her prescription (and again, this person is the nominee for Surgeon General of the United States) is for salvation through orthorexia.

Orthorexia nervosa is an eating disorder—unrecognized by the DSM or the APA, but one that’s been kicking around the medical literature for the better part of two decades—that focuses not on the quantity of what one eats, but the quality. It’s an obsession with food purity, rooted in a lot of different philosophies that Means and her ilk like to play with: raw foodism, macrobiotics, veganism, carnivorous diets, keto, etc. At its extreme, it becomes a compulsion, one that can lead to social isolation, anxiety and malnourishment, like other forms of disordered eating.

An orthorexia nervosa patient becomes fixated on their diet—whether, for example, it contains seed oils or artificial dyes or sugars or carbs. They may cut out entire categories from consumption and, according to the National Eating Disorder Association, may evince “a feeling of superiority around their nutrition and intolerance of other people’s food behaviors and beliefs.” After all, as Means points out, “Bad Energy leads to broken cells, broken organs, broken bodies, and the pain you feel.” Listen to me or you’re broken is a pretty strong message! One that screams orthorexia.

I have a funny perspective on all this, because I grew up with a very different, but no less demanding, form of orthorexia. I grew up keeping strictly kosher, following a complex and majestic system of laws extrapolated from Leviticus 11’s long list of prohibited animals, and a simple, but thrice-repeated commandment in the Torah: “You shall not boil a young goat in its mother’s milk.” Now, avoiding the consumption of Egyptian vultures and mole rats is pretty straightforward, but the Sages and successive generations of rabbis, and the social pressures of relative prosperity in America, engendered a wildly complicated set of guidelines that I followed scrupulously until roughly a month into my freshman year of college (and still do when I’m at the houses of literally any of my relatives).

There are the separate pots, pans, and flatware for dishes with dairy and dishes with meat, plus whole other layers of cross-contamination concerns. There’s a thicket of source texts spanning centuries, not to mention a modern corpus of responsa rabbinic Q&As about specific kashrut questions bearing it out. There are different laws about glass, metal, and ceramics, and how they convey or retain contamination; hot and cold foods, likewise; and some reflections of medieval fixations with, say, the status of certain items as “sharp foods” (garlic, radishes, vinegar, etc) and their interactions with meals and implements. Sometimes the complexities involved make it read like an LSAT puzzle, but I more or less breezed through, since I was born to it. I will admit to very definitely spacing out and messing up my implements more than once even as a kid—and far more so now that I’m less accustomed to the strictures of the system.

If you think about it too much, the whole thing really could drive you to distraction (or writing a letter to your rabbi about soup). Here’s the thing, though: the reason for all this hoopla was always pretty clear, and it boils down to: Because God Said So. Laws in Judaism are divided into, broadly, rules that have reasoning accessible to humans, like “don’t murder” (odot), and reasons only understandable by the Divine (chukim). The entire system of kashrut—which even without additional rabbinic complications tells us to jettison all shellfish straight off the bat—falls into the latter category. No one questions that part of it. It’s just what God wants, so you do it.

There isn’t really a clear mechanism of divine punishment for violating kashrut’s rules (there isn’t a standardized Jewish afterlife, nor standardized punishments for different forms of sin post Temple-sin-offerings, even). It’s just something you do because God wants you to, and all your neighbors are doing it, and you want to be able to host your family and neighbors and not be judged about it. I still remember a mild fracas when my mother accidentally bought a non-kosher salad dressing from the usually reliable Ken’s brand and served it at a Sabbath lunch—scandal!—but it was resolved by throwing out the salad, which I didn’t mind at the time.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

There’s an arbitrariness to it all that makes wangling the details alternately exasperating and weirdly satisfying. These aren’t moral judgments, per se. This is about trying to obey God as best we can, through cutlery. There’s virtue in obedience to an arbitrary law that you know is arbitrary; that’s an entirely different classification than, say, not murdering, or stealing, or whatever. Yes, this is fully a fixation on purity, and there’s an absolute minefield of potential sin involved, but it’s closer to a logic puzzle about obedience than it is any kind of heavy-handed morality play. There’s no essential ethical reason why you can’t have a cheeseburger; it’s just that God doesn’t want you to have a cheeseburger. So, you keep your cheese and your burgers separate in service of holiness.

And that’s that on that. These systems are more or less fixed: while they may change according to the availability of new foods or changing social mores (it took the kosher world many years to accept sushi, but now Orthodox Jews are among its most loyal soldiers), the basic tenets of the system hold steady. We still believe garlic and onions are “sharp” foods because a twelfth-century sage born in the Rhineland put it in a commentary on another commentator on the Talmud (which is commentary on the Mishnah, which is commentary on the Torah), and so garlic and onions have been “sharp” for the last eight hundred years. And the underlying reason is always the same: this is our best approximation of fulfilling God’s arbitrary will.

My point is, I’m intimately familiar with systems of eating that involve a lot of label-gazing, head-scratching, and consideration of ingredients. The irony is that, even though I lived through two decades of religious dietary strictures of byzantine complexity, it never felt half as much like a story about sin as Casey Means’ book does. In Leviticus, God never promises a longer, healthier, pain-free life if you avoid breaking any of the dietary laws. He never promises anything, except avoiding becoming ritually unclean.

By contrast, the Instagram orthorexics explicitly declare that you’re broken unless you keep up with an ever-shifting codex of purity that, incidentally, involves quite a bit of discretionary spending. Sure, two sets of cutlery and kitchenware is a big outlay. But Means wants you to buy, at minimum, wearable activity trackers for your movement and sleep; a food journal; blue-light-blocking glasses; access to a sauna; charcoal and reverse-osmosis water filters; a glucometer; and a whole new set of pantry staples (she even specifies a seed-oil-free hummus brand.)

Living this way is expensive, and I guarantee you none of these principles (except possibly eating vegetables and sleeping) are going to stand the test of eight hundred years. Or even eight months, probably. And the goal is not service to God or to others but to the self and the body. It’s good to have a healthy body, but it’s not a moral requirement to be healthy. Yet Means sets out her Good Energy commandments in the context of a long complaint about societal decay, about the ways in which American decadence has led to American pain, and so on. It’s a familiar message to anyone who doesn’t look like an Instagram wellness influencer. And the promise of membership in an elite cadre of the healthful herd, as distinct from the slothful, has an explicit moral dimension. You are what you eat, is the siren song of the wellness industry. And this applies in both the negative and positive senses.

So it’s fitting that the health administrators Means is gunning to join have explicitly stated similar views over the past weeks, linking not just health to diet, but diet and health to morality, and even to one’s worth as a human being. “Maybe we need to treat more diabetes with cooking classes, not just throwing insulin at people,” FDA commissioner (AND PANCREATIC SURGEON) Marty Makary, told Fox News this week, blaming diabetics for being fat and ignorant. It’s an innovation no one has ever tried before, while also insanely suggesting the most expensive healthcare system in the world is “throwing insulin” at anyone. Comments from the MAHA ghouliverse earlier this month were even more explicit. Dr. Oz, somehow the administrator of Medicare and Medicaid in what is, again, an ongoing nightmare, has repeatedly touted the idea that it is a “patriotic duty” to be healthy, because “healthy people consume less healthcare resources.” (It’s also a “patriotic duty,” Oz said more recently, for parents to feed their kids vegetables so they are fit for military service.)

Meanwhile, Nebraska moved to ban the purchase of sugary foods and drinks by those on SNAP governmental food assistance, as other states clamor for similar waivers with the open approbation of HHS Secretary RFK Jr, because God forbid a poor kid gets a fucking cookie. This is the elite gang of weird-faced guys that Means is gung-ho to join, and it makes perfect sense: all of them are members of the orthorexia nervosa superteam, obsessed with the purity of their own food and everyone else’s, and imbuing it all with levels of moral judgement made all the more ghastly by the amount of power they wield. Eat this, not that, or you’re broken, unpatriotic, and a waste of resources. (Meanwhile, as they wax poetic about microbiota and sugars, this crew of malevolent clowns are actively restricting access to vaccines, lifesaving medicines, and doctor visits—the better to blame people who subsequently die for not having eaten enough fucking asparagus, or whatever.)

Means et. al. offer just as many restrictions as any religious dietary system, but in a context of profound moral vacuity: they posit that failing their dietary tests is a matter of one’s worth as a person, and that, at the same time, illness is de facto proof of having failed the dietary test. There is no winning, except through obedience, hypervigilance, and perpetually proving that you have the trim physique to justify the expenditure of healthcare resources. Under the openly arbitrary system of kashrut, eating a cheeseburger doesn’t make you less of a person, or more of a burden on your community. It means you’ve pissed God off, which is fundamentally your own business. You are still God’s creature even if you’ve annoyed him; and none of it reduces the moral obligation of your community to aid you in need.

And more to the point: all of us die, no matter how many lentils and salmon burgers and green smoothies we consume along the way. Most of us get sick before we die, one way or another. No matter how much charcoal you filter your water through, you will return to dust, in—give or take—threescore and ten. How much of that time will you spend triple-checking labels for dyes and seed oils, and judging other people as unworthy of life if they don’t do the same? Orthorexia pits you against other people, placing you at the apex of a food pyramid composed of the righteous and the unworthy.

MAHA is, above all things, the apotheosis of a puritanical American tendency to blame the ill for their illness, the poor for their poverty. It’s a tendency so deeply-rooted it oozes out in all sorts of ways, but none more dangerously than the hideous and nonstop barrage of dietary judgements about food. I left kashrut and tasted the forbidden quite early in my adulthood. I wouldn’t go back. But at least I knew it was arbitrary; at least it had the breath of the capricious divine on it, with a little bit of wonder; at least it never claimed to be a system for sorting who should live, and who should die, and who should be judged for dying. No one but man, and man in a society gorged on judgement and predation, could ever come up with such a thing. That is the broken thing; that is the illness; and healing it will be a task for all of us, and all our lives long.

-

This sounds like the grocery-store version of the Prosperity Gospel: if you're not perfectly healthy, then it must follow that you are morally unworthy.

-

This is great.

What you said, Nance.

-

When I was twelve my mother died of a lifelong anorexia nervosa (the death certificate says it was “marantic endocarditis caused by a.n.) that was interspersed with bulemia. She and my father adopted me because her reproductive system had basically shut down from starvation and organ dysfunction. All through her life she would have times when she’d pass out and fall to the floor, and in my little kid apprehension I would keep thinking she had died. Over and over. When I see this recent obsession with purity and perfection centered on food and diet and mortification of the flesh it brings back all the trauma of childhood, and I find myself truly hating these hucksters and maniacs preying on so many vulnerable people.

-

Excellent extended metaphor! Also makes me feel relieved that I keep kosher by ingredients, not by dishes or even kosher certification. I maintain the arbitrary commandments by just being vegetarian, mostly. And fucking up sometimes is ok, this is about my relationship with HaShem, and every relationship needs a little space sometimes

Add a comment: