Writing Under Water

Faded the flower and all its budded charms,

Faded the sight of beauty from my eyes,

Faded the shape of beauty from my arms,

Faded the voice, warmth, whiteness, paradise—

There are times when I flee my work. I flee from words that I create, because I don’t want them anymore. The Russian term for “writer’s block” is страх белого листа, fear of the white page, and when that fear comes over me, it turns me to jelly. It’s not, precisely, the whiteness of the page I despise—or the screen, really, with its mimicry of paper, as I shuffle pixels around haplessly. What I fear is myself, and my own inadequacies, which shout at me louder than anything I can commit to paper.

There are other times when the words fly out of me, and I feel I can make the English language sit up and dance like a show dog. The Artemisian days when each word is an arrow shot surely from a quiver safe somewhere inside me, slicing through the air to strike true, into the rump of whatever I’m skewering, or into the good bright heart of whatever I praise. The rest of the time, I muddle my way through, neither in one state nor the other, shunting my own inadequacy to one side, realizing that nothing will be crystalline today, but neither will it be easily shattered. I take pride in having, for the last decade, shaped words to all kinds of ends, written two books even, and hundreds of columns, for my own publication as well as famous publications, making a small name and a modest living off turning a sentence just so, shaping a paragraph just so, affixing a metaphor or a clause or an em dash with precision and with pleasure and pride.

That’s why the times I can’t write, flee writing, fear writing, feel so corrosive. Lately I have been in the full grip of such a time, dangling in the maw of my own fear, breathing in its terrible musk, my bowels gone watery, my legs weak, my mind folded in on itself, refusing to produce. That is what I ask of my brain all the time, and lately it refuses me, leaving the acreage of the white page gaping inside me and my whole self blanked out. The words that came to me so easily are sluggish now and abraded to an impossible thinness. Such grace as I have ever had deserts me, and I feel as if I write wrong-handed, everything at a wrong angle, a fractured wrist bone, a dry creek bed, a frayed bandage over a great wound.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription.

My life has shrunken lately to such a small pinpoint that the work is all I have to justify it; when I lose that capacity, as I have recently, when it’s knotted up and shriveled like a tableful of dried-out sausage casings, I feel I have vanished from the world entirely. And I flee into myself so deeply it’s like (I can feel myself overusing similes; I can feel the poor quality of this work like I could feel bad paper; I am overladen with metaphors because I cannot hold anything, anything else) being underwater. Just under the surface. I hold myself just underwater where everything comes to me slowly and the world is muted blue and dull, hoping a time will come soon when I’ll thrash back to the surface and breathe and see the gold light shining off the sea-peaks and desire no longer to be submerged. I hold myself still and wait. Underwater, or in a cave, or boarded into the plain pine box that will someday be mine. I suspend myself and hope the desire to reemerge will come on me sometime soon. That the white page will no longer look like the curdled milk of all I was and all I wanted to be.

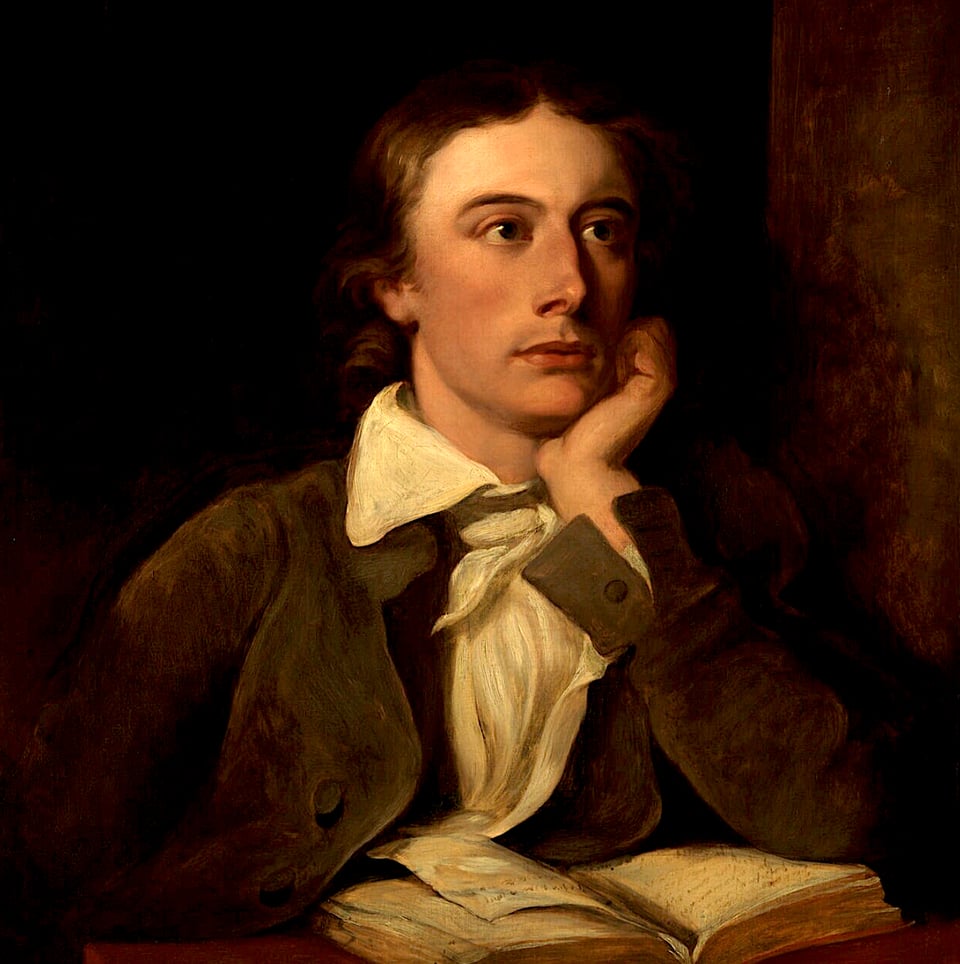

John Keats, perhaps the greatest poet in the English language, died at twenty-five of tuberculosis, in Rome, far from his native England. Wilfred Owen, whose youthful demise is inseparable from the tragedy of his poems, was also twenty-five when he died, on the fields of Flanders a week before the Armistice; Egon Schiele, the tortured and marvelous Austrian Expressionist, died at twenty-eight; Emily Brontë was thirty, and only wrote Wuthering Heights; Percy Shelley, twenty-nine; Sylvia Plath, thirty, when she finally ate herself alive. In the depths of my self-pity, hiding underwater, I think: I’m too old now to die tragically young. And too little of a genius for it to be tragic in the first place. This is, of course, too grandiose a thought to voice unironically, so pretend I am saying it with irony; pretend I don’t wish I was one of those who died young and stayed immortal; pretend I don’t want to be remembered, when I die, through the words I wrote, and hum against new minds each year like a perfect lute.

I wanted to be a genius once. I was certain I was a genius once. When I was very young, and not yet bruised, and not yet having met true genius and been humbled by it. The vigor of my youth was misspent, spent in a torrent of words but not the right ones, not the holy-light ones, the ones that feel like singing a tune you half-remember even as you create it, a song that should be in the world because it is of the world as you are of the world. Then come the treacherous subjunctives, those cliffs of the mind and the heart: if I’d been born a man… if I’d been born earlier, when it was easier to make a living writing… How I flay myself for not having a steady job, and how few jobs there are—better writers than me are jobless now! But if I were a man I’d never have known what I know; if I’d been born earlier I would be a different person; a job means confinement and precious little security, in the world of journalism at present; if is a treacherous slick road and a bad Kipling poem and little else. Underwater, I let the ifs swim past me like a school of black minnows and go, and I abide.

I meant to write about California drowning in a thousand-year storm today, and how much faster the epochal tides are turning—fires and cyclones, wild seas and torrents and droughts. How a thousand years condense into a haywire world hopped up on manmade accelerants. Or about the snarled and vicious border deal the Senate is wrangling over. Instead, having curled so fully into myself I am snaillike, I offer only this grim little whimper. The act of writing is so often a form of self-cannibalization that soon your own flesh is the only thing you can taste, if you’re not careful you’ll eat yourself to the bone, to the dark marrow.

It’s hard to know your prime passed without you realizing it; harder to hope another prime will arise, a better time, when the words flow like sap from a tree in a winter clearing, sweet, ungummed, from some deep taproot under snow. It’s hard to stay poised under this inner water, floating in suspension, in a little sac of wilful retreat from all the world. It’s harder to lift my head, to breathe real air, emerge in the hope that the rest of me—the part of me that is facile and careless and joyous in words, the part of me that arcs out quick and snags the flesh of argument in her jaws, the part of me eager for life—will emerge after. I pray it’s soon. It’s lonely underwater, lonely and blue, airless.

Keats wanted to write more; he didn’t want to tear his bloody lungs up in Rome; he will always be twenty-five, and always immortal. Though it was only three years before he died that he wrote—

Many and many a verse I hope to write,

Before the daisies, vermeil rimm'd and white,

Hide in deep herbage; and ere yet the bees

Hum about globes of clover and sweet peas,

I must be near the middle of my story.

Dear John, king of the nightingale and the Grecian urn, you did not know everything. You were nearer the end than you knew. How dark your eyes are in the posthumous portrait, bigger than marbles, home of a whole night sky. What a pity the rest of us have to go on, waking up and writing, obscure and artless and alive. To the sea air and the sun on the wind-racked branches. To the sluggish river and the rats and the woman who sings as she walks down the street. Many and many we are, more than your verses. Weak and weary, held together by coarse and fraying will, we are alive.

Add a comment: