We Keep Us Safe: On Antifa

This past Saturday, Donald Trump announced that his administration would be deploying federal troops to Portland, OR, authorizing the military to use “full force” in the “war-ravaged” city. The president cited “domestic terrorists” singling out Antifa, the leftist activist group that has become a bogeyman to the right—and the potential pretext for a massive crackdown on American civil liberties. Just today, in his speech to the gathered commanders of the Armed Forces, Trump reiterated his intention to use the military against “the enemy within.”

Reading about the developing story, I was reminded of a section in Talia’s 2020 book, “Culture Warlords,” in which she wrote about Antifa in Portland amidst the rise of white-nationalism during the first Trump administration. This week’s newsletter seems like a good time and place to revisit Talia’s words.

— David Swanson

One thing to make clear at the outset, when describing antifascist activity, is that the vast majority of it is nonviolent. In fact, antifascism is a defensive posture—it rises as fascism rises, and falls as fascism falls, in a well-documented pattern that has lasted for decades. In the Trump era, antifascist organizing began to rise during the 2016 election season, as the white-nationalist movement grew unmistakably emboldened by the openly racist rhetoric spewing forth from the Trump campaign. As hate groups rose in prominence, antifascists began to coalesce around the idea of countering their organizing, protecting the vulnerable from violent hatred. The principal goals of most antifascist groups and individuals are to prevent violence from having to occur in the first place. Which isn't to deny that the movement condones some degree of violence in pursuit of quashing fascist organizing. Sometimes a thrown punch in a street brawl is a way to keep the next fight from happening with knives—or guns, always a potent factor in the American public sphere.

But long before that punch is thrown, antifascists act behind the scenes. Again, this doesn't make catchy B-roll for the news, and antifascists are famously press-shy in the first place—largely because they want to avoid harassment by their far-right foes. But much of antifascist activity takes place in the form of research, infiltration, and perhaps most of all "doxing"—revealing the names, locations, and occupations of members of hate groups.

This can entail everything from reviewing footage of hate rallies and matching faces to Facebook profiles, to elaborate plots involving undermining fascist groups from within by posing as their members online or in person. Antifascists aim to be wherever fascists are, working to sow discord, engender paranoia and discourage-ment, and ensure that there is, above all else, a social cost to fascism, racism, and virulent homophobia and transphobia.

In the Trump era, that social cost has been vastly eroded. As the writer David Roth noted in a New Republic article, one of the unofficial duties of a president is to "shape the culture in ways that reflect their own values or anti-values, politics, and vibe."

Under Trump's presidency, the culture has a potent driving force that promotes—and thus erodes the social cost of—misogyny and a range of racism from the casual to the brutally open. From the early days of his campaign, Trump both advanced racist invective and displayed an unsettling degree of comfort with racist violence. When supporters of his, during the campaign, violently beat and urinated on a Latino homeless man, the future president commended them as "passionate." A president who has openly flirted with white nationalism since the inception of his campaign, and has an openly white-nationalist chief immigration adviser in the form of odious Nosferatu figure Stephen Miller, imperils the fragile social contract that, for a few decades at least, made open white nationalism a socially unacceptable position to take. The gamble that antifascists make with their doxing is that, despite the corrosive effect of White House white nationalism, there are still neigh-bors, employers, and casual friends in communities across America who may be uneasy with members of organized hate groups in their midst.

Antifascists and the police have a particularly antagonistic relationship. At the tip of this iceberg of resentment is the street-theater aspect of anti-fascist organizing—the brawls and melees when fascist speakers or rallies invade a city. As white nationalist and far-right extremist events descend into violence between antifascists and fascists, police forces throughout the country have disproportionately focused their attentions on leftists. Excessive police violence, lopsided arrest counts, and the punitive posting of mug shots associated with leftist activists have added to the hostility that already exists between leftist organizers and the police. In turn, anti-fascists have refused to cooperate with police on numerous occasions, including in the cases of investigations into fascist and far-right violence.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

This pattern has been documented in particular detail in Portland, Oregon, a city that has weathered an extraordinary, sustained, and bloody series of far-right incursions. Evidence emerged, reported in local publications like the Willamette Week, of extensive coordination between the Portland Police Bureau and far-right activists. One police lieutenant, Jeff Niiya, engaged in chatty, discursive, and even jokey texts with Joey Gibson, head of the far-right extremist group Patriot Prayer.

Patriot Prayer has staged numerous rallies since 2017 in Portland that attract openly white-supremacist groups, such as the neo-Confederate Hiwaymen and the racist group Identity Evropa. During the era of the coronavirus, Patriot Prayer became enthusiastic participants in "ReOpen Oregon" rallies that attracted a menagerie of militias, white nationalists, antigovernment extremists, and conspiracy theorists.

On one occasion, police discovered a group of Patriot Prayer supporters perched on a roof overlooking a protest route with a number of rifles, but made no arrests. Police have been far harsher with left-wing protesters: On August 4, 2018, at a Patriot Prayer rally, police threw stun grenades into a crowd of counterprotesters, causing a minor brain hemorrhage in a leftist protester when a grenade hit him directly in the head. The Daily Beast's Arun Gupta, who was present at the far-right rally and counterprotest, summarized the views of leftist activists: "The city was turned into a war zone by a police force seeking to protect hundreds of outside extremists—Proud Boys, neo-Nazis and neo-Confederates among them—who came dressed for combat."

It's worth noting that police forces in America are near-uniformly aligned with the political right—and that the political right, in turn, have adopted the "protection" and "respect" of police forces as part of their cause. In response to Black Lives Matter protests against police brutality, right-wingers adopted the "Thin Blue Line" flag, a color inversion of the American flag that emphasizes the colors black and blue; New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie has called it a "fascist flag," for its unmistakable alignment with state violence, and the accompanying rhetorical push for unquestioning obedience to the state.

Law enforcement unions overwhelmingly supported Donald Trump during the 2016 presidential election, and the International Union of Police Associations, representing more than 100,000 police officers in the United States, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico, endorsed Trump for reelection in 2020. The avowedly white-nationalist "law and order" presidency of Trump matched the IUPA's goals, and the association's statement cited with approbation the resumption of the federal death penalty and facilitation of police access to military equipment. Trump has also publicly endorsed police brutality against suspects in general and protesters in particular, expressing a public desire for the "good old days" of unchecked violence against leftist protest.

"Every top Democrat currently running for this office has vilified the police and made criminals out to be victims," the IUPA said in a statement endorsing Trump. "While his candor ruffles the feathers of the left ... he stands with America's law enforcement officer and we will continue to stand with him."

Police rhetoric extends beyond support of right-wing candidates to an outright detestation of leftist political causes. This naturally sets the stage for profound conflict with antifascists, who are overwhelmingly politically aligned with the far left. One particularly unhinged exemplar of police rhetoric on antifascism came in the wake of a 2017 far-right rally in Boston, in which a number of far-right "free speech" activists assembled on Boston Common to make a stand. Coming a week after Charlottesville's infamous Unite the Right rally—and after a national furor over Trump's seeming endorsement of the far-right marchers—the event drew just a handful of right-wing attendees, while thirty thousand to forty thousand citizens marched in counterprotest. The event was hailed by press and attendees as largely peaceful, and a forceful rebuke to a newly emboldened far right.

Yet the views of the police starkly differed from those of the public. In the Fall 2017 edition of Pax Centurion, the publication of the Boston Police Patrolmen's Association, Officer James Carnell, a veteran of the Boston Police Department, let loose in an essay titled "ANTIFA/NAZIS: Want Six or a Half Dozen?" Calling the protest an "anti-police riot," Carnell condemned "ANTIFA savages" and "lemming-like college kids [who] chanted and sang like North Korean civilians at a rally in Pyongyang." Although no casualties were reported at the event, Carnell nevertheless fulminated in a striking advocacy of violence against protesters (emphasis in the original text):

ANTIFA, which allegedly means “ANTI-fascist,” is in fact the epitome, the definition of fascism itself: strongarm violence and intimidation by lawless groups seeking to impose their will on the silent majority.... The only way to defeat these savages is to fight fire with fire. Good can and must be allowed to defeat evil, but kind words and kisses are no match for strongarm violence and lawlessness. You WILL BE unmasked and arrested as a disorderly person if you do not disperse NOW.... Mad dogs and mobs can sense indecision and weakness. Only the surety of violence meeting violence and that they will be arrested and prosecuted deters rioters.

Antifascists are thus faced with a dual foe: both the violence of far-right groups whose goals are explicitly oriented toward violence and genocide, and the hostile forces of the state. The structure of the conflict is often referred to as a "three-way fight." The three points of the triangle are the state; anti-statist far-right groups who seek the violent overthrow of civil society; and antifascists themselves, who perceive themselves as the ole bulwark of community defense against both a police force aligned with government-sanctioned white-nationalist violence, and the far-right groups that seek to engage in vigilante violence.

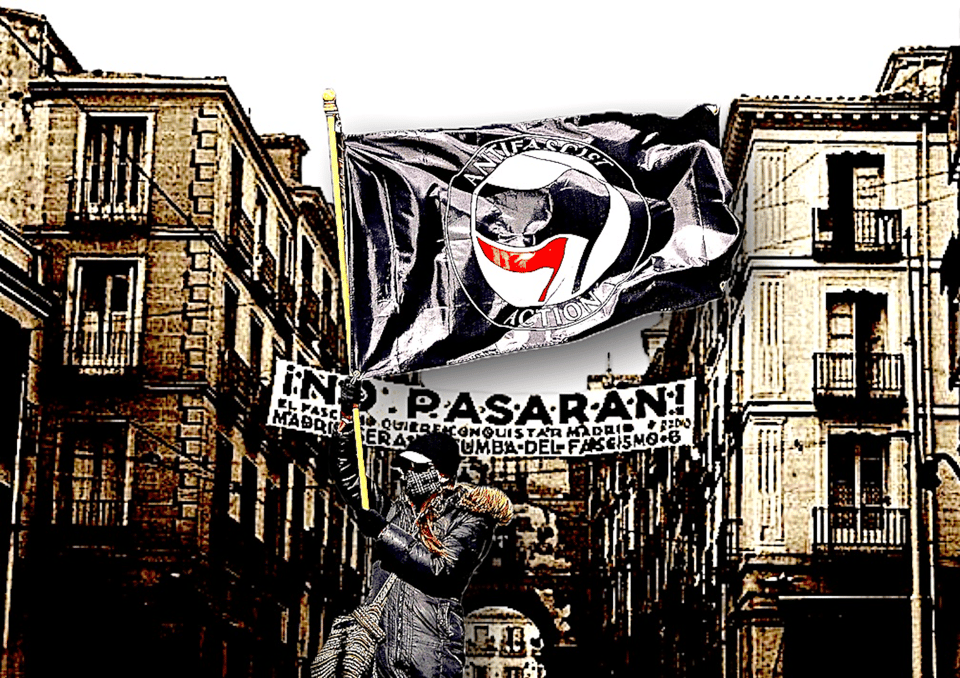

In his eloquent (and much-loathed on the far right) book “Antifa: The Antifascist Handbook,” the scholar Mark Bray lays out a capsule history of the antifascist movement, placing its beginnings with militant anarchists who rose up against Benito Mussolini's fascist Black Shirt squads in 1921. The movement, led by the dashing Argo Secondari, called itself the Arditi del Popolo—the People's Daring Ones—and at its height had some twenty thousand members, though it was ultimately overwhelmed by a confluence of Mussolini's repression and movement infighting. In the mid-1930s, as fascism ascended in Europe, foreign volunteers converged to defeat the incipient forces of Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War, from 1936 to 1939.

One of the chief mottos of antifascism stems from the Spanish Civil War—¡No Pasaran! or "They shall not pass," famously employed during the Siege of Madrid by Spanish communist Dolores Ibárruri in 1936. Antifascism had many other loci in Europe in the 1930s, as the rise of authoritarian governments menaced the continent, and communists, socialists, anarchists, and targeted minorities fought back in bloody street brawls. It also surfaced in the United States, as Jews brawled with fascist Silver Shirts and members of the German American Bund.

World War II often stands as an emotional point of appeal among those who oppose the far right today. Many liberals use the talking point that America, or their grandparents or parents, fought Nazis in that war, which looms so large in the American imagination as the most just and triumphant conflict of the twentieth century. However, Bray and others largely skip over this chapter when recounting the history and ideology of antifascist work. This is, above all, for the simple reason that antifascist work as it is understood by most contemporary antifascists is, by definition, performed by nonstate actors. You can't have an antifascist, government-sponsored army with tanks and a budget in the billions. Stalin wasn't an antifascist; he was a dictator fighting off a threat to his absolute rule, and using a massive army to do so. Many antifascists are anarchists; they work to create community defenses and impose a social penalty on far-right organizing without the intervention of the state.

Across the world, since the end of World War II, anti-fascist groups have arisen from communities affected by far-right organizing, and engaged in activities from sabotage to street conflict in hopes of nipping it in the bud. A commonly used slogan is "We keep us safe": antifascists use the notions of community and solidarity as driving forces for their activities. Nonstate actors who consider themselves to be in community with one another, and more broadly with those at risk of harm from far-right organizing, form the core of antifascism in America today. Street fighting is only a small part of a much broader set of activities, from flyering neighborhoods where known neo-Nazis live to make residents aware of the neo-Nazis in their midst; to compiling dossiers and feeding the information to journalists; to blogging; to providing security for events and individuals who might be the targets of hate groups.

There are about eleven thousand slippery-slope arguments that have played out in the American press, particularly after a masked and still-unidentified antifascist very publicly punched white-nationalist ideologue Richard Spencer right in the kisser in 2017. Debates have raged among pearl-clutchers about the risk to democracy posed by protesting against far-right speakers like Milo Yiannopoulos and Heather MacDonald and Michelle Malkin—although retaliatory incidents, such as when a protester was shot by a fascist at a Yiannopoulos protest in Berkeley, California, requiring extensive surgery, have received far less airplay.

There is a sense in the liberal imagination that antifascists are roughly on the "same side" as liberalism's stuffiest pundits, who debate ideas largely in the abstract; thus, antifascists must be far more heavily policed and chastised than their neo-Nazi counterparts. "Free speech" arguments against antifascist organizing are particularly popular among mainstream media personalities and journalists.

These arguments belie the obvious facts of antifascist organizing on the ground. Antifascists have specific targets; act in self-defense and in defense of their communities; and, far from evolving into some enormous power that seeks to constrain speech to greater and greater degrees, antifascist organizing has waned or even disappeared when various waves of far-right organizing recede. As Bray notes in his book, this pattern has been observable since the 1950s, when Jewish Brits and their allies opposed to the remnants of Oswald Mosley's fascist movement in that country brawled with them for years until the Mosleyites ceased to publicly organize. Were the slippery-slope argument as plausible as finger waggers seem to believe, success would merely whet antifascists' appetite to suppress right-wing speech, or any speech deemed unacceptable to their nascent authoritarian im-pulses. But this has never been the case; for more than seventy years, antifascists have sought to dog and drown the threat posed by fascist and far-right organizing, and have been content to disband when the immediate threat subsides.

Antagonism between antifascists and the mainstream press is high because of a broad institutionalist bias from the media itself. This is not necessarily a partisan impulse, but rather the understandable preference of journalists and news organizations to rely on official—and seemingly authoritative—sources. Given the antagonism between police, federal authorities, and antifascists, official sources are wont to classify antifascists as a violent, chaotic force of disorder. While journalists frequently pride themselves on speaking truth to power, many local news outlets rely on robust relationships with police forces to report events as they occur.

Antifascists, who, for the most part, prefer to remain anonymous, rarely offer up granular alternative narratives in a press-friendly manner, and lack the authority of officialdom in any case. They are wary of the police and the press because they've traditionally not been treated particularly well by either institution. Images of antifascists in the popular consciousness envision a mostly white, mostly male crew of commandos, or college students playing tough. In reality, while the demographics are necessarily difficult to parse in a group that keeps itself intentionally under the radar, most of the antifascists I've interacted with were women, people of color, or both. One antifascist source with knowledge of the matter told me that most major antifa crews in the United States are led by women.

Neo-Nazi groups also take advantage of the media in ways that date back to the 1960s heyday of George Lincoln Rockwell—and which are equally effective in the present. To return to Portland, national media coverage of the violent political street melees that have broken out in that city has often focused exclusively on the fact of violence between political groups—without sufficient examination of its causes. Patriot Prayer rallies in Portland have attracted so many skinheads and white nationalists that the city has functionally been subject to periodic invasions by violent right-wing ideologues. I say invasions because, as in Charlottesville, far-right groups have repeatedly employed the strategy of purposefully rallying in cities that are broadly liberal and have a strong left-activist presence. Joey Gibson himself is a resident of Vancouver, Washington, a suburb of Portland, but does not hold his rallies in that city or even in his home state.

Hoping to attract headlines from the press, these rallies explicitly aim to prompt strong reactions in the communities they invade, busing in far-right activists from the Pacific Northwest at large. Like George Lincoln Rockwell traveling to Boston and New York, far-right extremists choose their locations carefully. The idea is to create sympathy-the sense that "conservative activists," as figures like Gibson often euphemistically call themselves, are under siege by violent leftists. The racist, genocidal goals of many of the groups involved in these rallies, and the presence of right-wing street brawlers who repeatedly, and on film, assault left-wing protesters is hardly remarked upon.

What's more, the fact of right-wing activists being an invasion-and that anti-fascists are the residents of a city and perceive themselves as defending it from hostile outsiders-has been obscured entirely, in favor of an oversimplified "melee" narrative. This kind of omission is inevitable in an American populace that expects agents of the state, from the police to the military, to have a monopoly on the use of violence. Stories of police murder routinely vanish without a trace, but the specter of a black-clad, militant force of civilians bears the exotic mystique of homegrown guerrillas. There's an element of novelty to it that eclipses the phenomenon of armed and violent right-wing groups—a phenomenon that has existed in the United States for much of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

While antifascism itself is roughly a century old, it has evolved, in the twenty-first century, to embrace novel techniques and technological advances. In some ways, it has never been easier to participate in everyday antifascist work, provided you have a good internet connection, a measure of patience, and the ability to engage in painstaking amateur detective work. Significant antifascist operations have focused on massive data leaks from fascist websites, such as the now-defunct neo-Nazi web forum Iron March, which operated from 2011 to 2017.

Iron March was openly anti-Semitic and racist, calling itself a "Global Fascist Fraternity," utilizing the fourteen words and proudly displaying press clips that called the site "Nazi Facebook" and an "international network that promotes race war." The site folded in 2017 for reasons that have not yet been clearly reported. On November 6, 2019, an anonymous antifascist going by the handle "antifa-data" released an info dump that revealed the email addresses, usernames, forum posts, messages, and IP addresses of Iron March's user base. Immediately, other internet users affiliated with antifascism, as well as journalists, began to comb through the data. The leftist Jewish publication The Jewish Worker created a searchable version of the database, which enabled anyone to find Iron March users in their city, search any term, and provide public comments on the data. And antifascist groups across the world began digging in.

From Alabama to Pennsylvania, from teenage neo-Nazis to members of the American military, participants in the fascist forum found themselves unmasked in public-to their neighbors, friends, and employers. The goal was simple: to check the cancerous growth of far-right organizing by imposing a social cost on the individuals who engage in it. From cybersleuthing to street melees, that is the sole goal of antifascists across the country; antifascism's goal is community protection, not genocide. And while any decentralized movement has its renegade factions and regrettable incidents, to establish a moral equivalency between those who combat Nazis and those who engage in Nazism is a profound societal mistake.

To those who find themselves uncomfortable with the operation of antifascists outside the comfortable bounds of institutions and, at times, the law, I remind you that the French partisans of World War II were acting illegally, while the Einsatzgruppen had the full support of German law. We tend to like our noble lawbreakers to be comfortably in the past, where time and death have sanitized them into heroes, and to suffer those who struggle against injustice in the present only grudgingly, if at all. Those who oppose a white-nationalist president, his allies in law enforcement, and a militarized state might consider moving beyond letter-writing campaigns to their congresspeople and engaging in the life-or-death struggle that motivates antifascists around the country and the world: the struggle of communities defending themselves against the nihilistic forces of violence, to build a better world by keeping the agents of genocide at bay.

Copyright © 2020 by Talia Lavin

Add a comment: