Turning Away from Disaster

It started, as great art often does, with a metamorphosis.

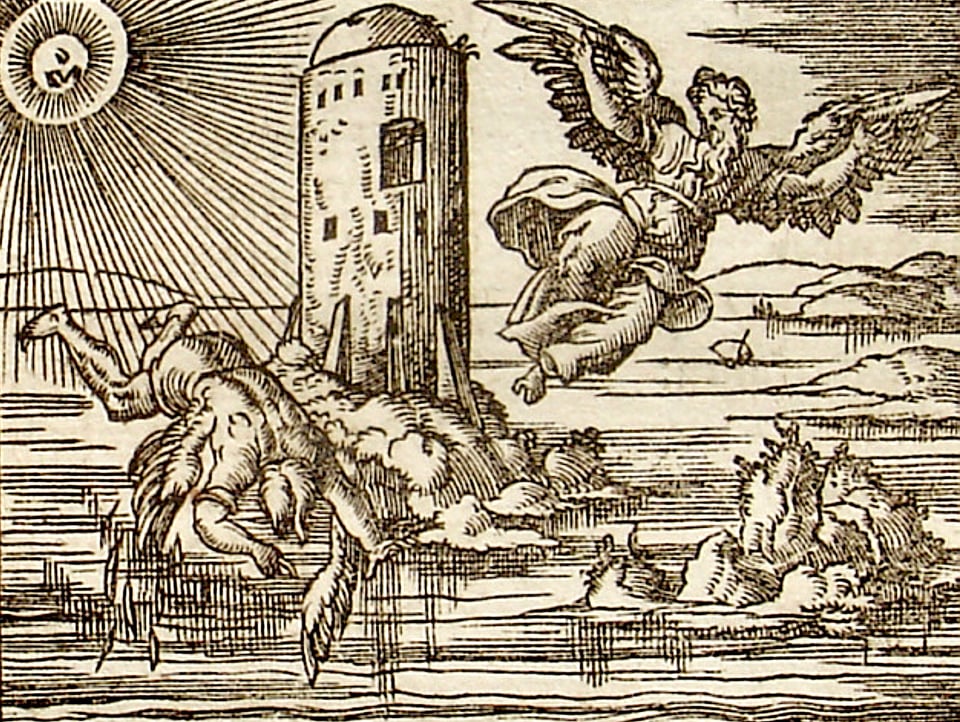

Or Metamorphoses—specifically, Ovid’s, the great canonical poet of the Ancient Rome. In Book VIII he records the fall of Icarus, the angelic boy who has become emblematic of hubris, he who first flew too close to the sun. His father, the great engineer Daedalus, made wings of wax and feathers and taught him to fly, only to repent it. A whole sea, the Icarian Sea, was named for the drowned boy, though this did not return him to his father.

Some angler catching fish with a quivering rod, or a shepherd leaning on his crook, or a ploughman resting on the handles of his plough, saw them, perhaps, and stood there amazed, believing them to be gods able to travel the sky.

...the boy began to delight in his daring flight, and abandoning his guide, drawn by desire for the heavens, soared higher. His nearness to the devouring sun softened the fragrant wax that held the wings: and the wax melted: he flailed with bare arms, but losing his oar-like wings, could not ride the air. Even as his mouth was crying his father’s name, it vanished into the dark blue sea, the Icarian Sea, called after him.

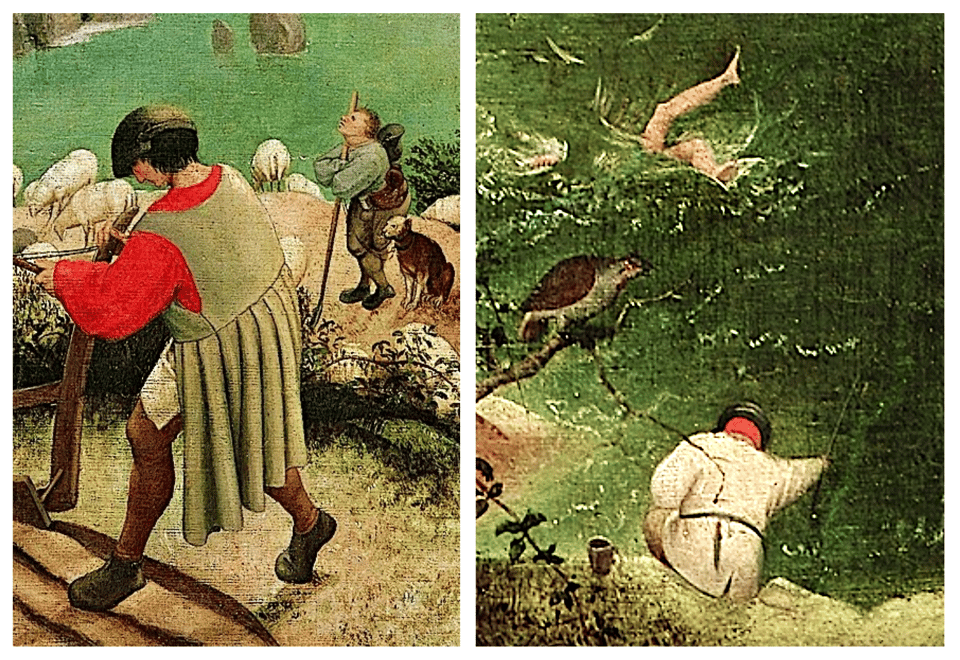

Approximately one thousand six hundred years after Ovid’s death, a Dutchman took up his brush and made a painting. It was called "Landscape With Fall of Icarus", and perhaps more than any other single painting, it has drawn from poets the art of ekphrasis—that is, written art that works to explain or augment visual art; exegesis, or explanation, or simple expansion on Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s brutal and perfect scene.

What Brueghel did was bring the angler and the shepherd and the ploughman to the fore, and not to depict any supposed wonder at these flying heroes. What he did was show how the triumph and tragedy of Icarus mattered less to the ploughman than his field, less to the angler than his fishing, less to the shepherd than even the mangiest of his sheep. No one turns their smooth round heads to the drowning boy, to his poor legs thrashing in the murky water. The furrow cuts deep in the hill. The shepherd gazes at a different patch of sky.

What Brueghel did was pluck at a cruel but necessary thread of human nature, and poets ever since have been unable to leave it be. They pluck and pluck at it—William Carlos Williams, W.H. Auden, Michael Hamburger. The simple and brutal image needs no words to couch it, but the truth Brueghel sieved from Ovid is one that can scarcely be left alone. It is too true to be left to rest.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription.

At some point in our childhoods, all of us realized—perhaps on a busy street one day, or on a highway traveling in a car behind and beside hundreds of other cars—that every other person we saw that day, every person we would ever see on any subsequent day, feels as much as we do. Wants as much as we do, thinks as much as we do, is as much as we are. That every other human is as fully human as we are.

To live, you have to constantly blunt this truth, drown it within yourself. Every time it snows someone skids off the road, and others with nowhere to go freeze to death; every time a bad law is passed, someone suffers; as I write this, nearly two million people are incarcerated in prisons and jails across the United States; thousands have died in the past several months in Gaza, and more are dying now; the breath of winter kills soldiers entrenched in Ukraine, bombs rain down in grainfields and in cities alike. The injustices being perpetrated are so vast that to even examine even one, even incompletely, could drown your soul. In this world, Icarus is always falling.

And yet we always turn back to the plough, the rod, the crook: to the necessity of life without being drowned in other lives, without being pulled down by the drowning. We direct as much sympathy as we can spare, perhaps a few dollars, a call or two, or perhaps less; to push oneself into full recognition of the humanity of those who suffer is to invite paralysis. To always push oneself to full recognition is to invite madness. I live in a city of millions and know so few; their passions are no less than mine, their needs no less than mine. And yet to live I must shoulder them aside, turn a war into a faraway spectacle, keep my elbows locked to push away the knowledge that somewhere in a state where abortion is forbidden a woman lies bleeding, a girl sees her life snuffed out like a boy fallen from the sky.

In Breughel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

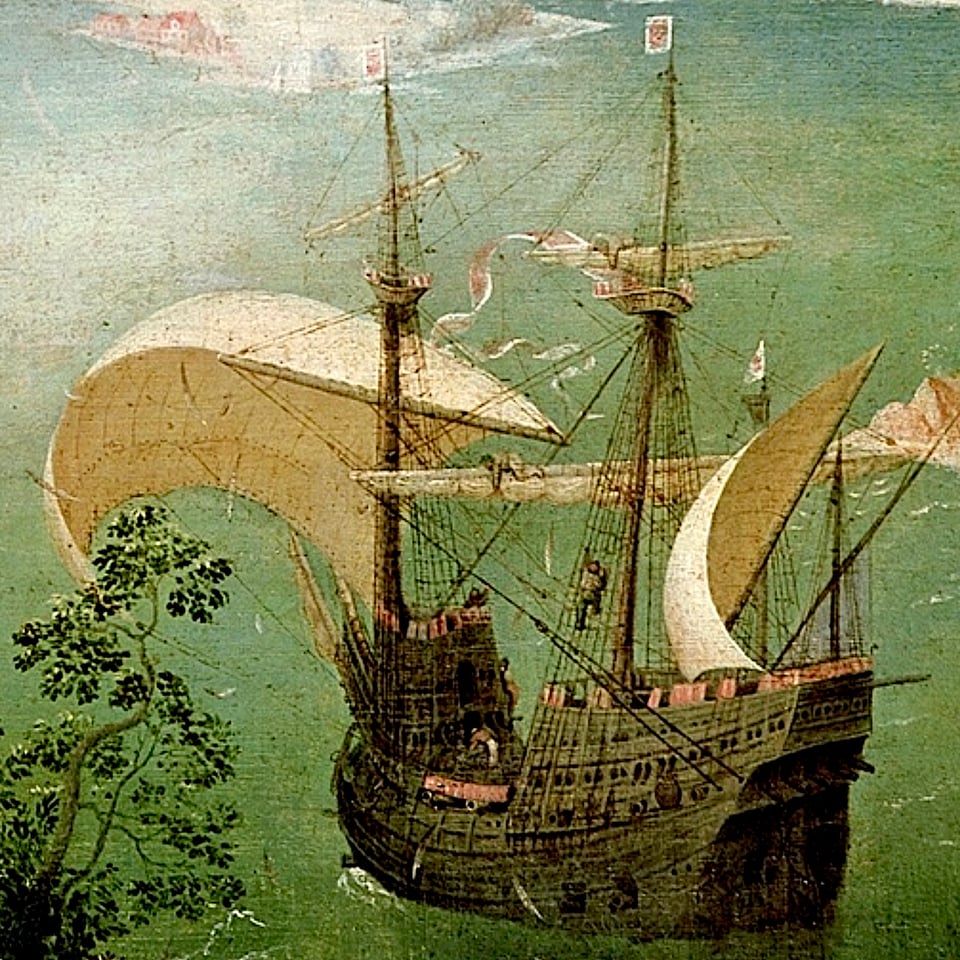

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

The great and terrible truth of human nature is that some of us strive and fall and the rest of us go on. The climate Cassandras who speak their terrible truths go unheeded, and the tempests that a warmed earth rouses will, we hope, sweep other people away. The dystopian future slips into the present but you keep your hand at the plough, because you have to. You could drown in the eyes of one Palestinian newly orphaned, one Israeli kibbutznik kidnapped, one Ukrainian drowned in sodden mud, one prisoner, one patient dying because they cannot afford medicine. You could drown, and to avoid drowning, you avert your eyes from the legs in the water up to the welcoming dappled sky.

According to Brueghel

when Icarus fell

it was springa farmer was ploughing

his field

the whole pageantryof the year was

awake tingling

nearthe edge of the sea

concerned

with itselfsweating in the sun

that melted

the wings' waxunsignificantly

off the coast

there was

a splash quite unnoticed

this was

Icarus drowning

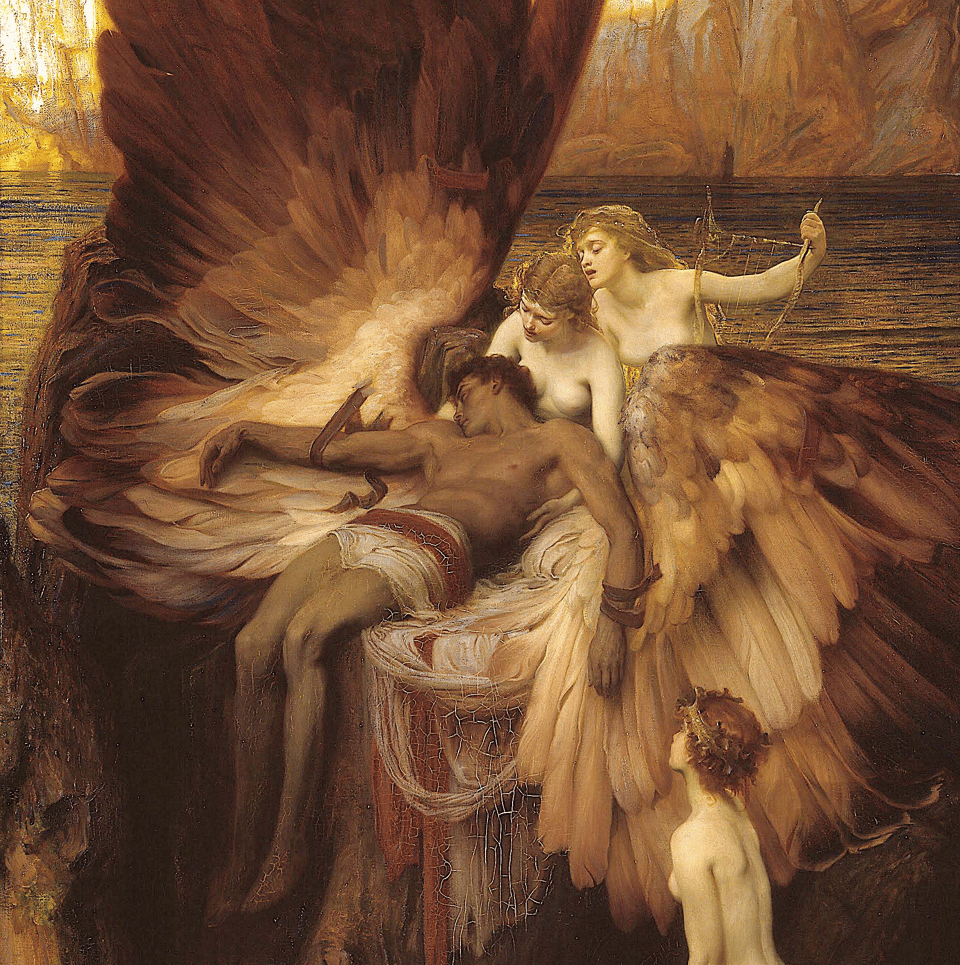

Icarus himself is a symbol of audacity, of heedlessness, and recklessness; in the painter’s rendering, and the poets’ rendering, he is something else entirely—he is the sufferer who goes unheeded. In this landscape the sea is nameless, though according to Ovid the expanse that claimed his bones bore his name in tribute. So many are drowning, and who will name a sea after them? How many fathers grieve who are not aloft on wings of unnatural artifice, whose names are not immortal in their own right?

And yet it is not wrong to live, even if, to live, we have to crowd out what we know, which is that each life—foreshortened, rendered hollow and cruel by privation, rendered stateless, rendered shelterless—is equal to ours. There is no moral ill in plowing the field of our lives and hoping the rich and yielding spring will give us our autumn harvest. It is the nature of being human: to be cruel because we must be cruel; to be ourselves only because to be otherwise is impossible, impossible as a boy arcing up to the brow of heaven.

The ploughman ploughs, the fisherman dreams of fish;

Aloft, the sailor, through a world of ropes

Guides tangled meditations, feverish

With memories of girls forsaken, hopes

Of brief reunions, new discoveries,

Past rum consumed, rum promised, rum potential.

Sheep crop the grass, lift up their heads and gaze

Into a sheepish present: the essential,

Illimitable juiciness of things,

Greens, yellows, browns are what they see.

Churlish and slow, the shepherd, hearing wings—

Perhaps an eagle’s–gapes uncertainly;Too late. The worst has happened: lost to man,

The angel, Icarus, for ever failed,

Fallen with melted wings when, near the sun

He scorned the ordering planet, which prevailed

And, jeering, now slinks off, to rise once more.

But he–his damaged purpose drags him down—

Too far from his half-brothers on the shore,

Hardly conceivable, is left to drown.

The illimitable juiciness of things; rum consumed, rum promised, rum potential. The sailor’s memory is feverish, the shepherd is churlish, the flock is hungry. The miracle and the tragedy happen stage left. Always the tragic miracle happens at the edge of the canvas, while we cut the turf of the hill, while we check our lines, while we live he dies. Icarus is always falling. It is our nature to look away and live, sail calmly on and leave the turbid waters where he dies.

There is no wrong in this, but there is no right in it either. It is simply the huge truth of human nature, a truth so huge, and so hideous and yet so natural in its aspect the poets cannot leave it alone. They poke at the slim legs that emerge from the blue-green sea, they shake the shepherd by his shoulders, saying, a boy fell here, stop and look. In Ovid’s telling the fisherman and the ploughman gawk in wonder and see gods. Brueghel saw better; he knew a drowning boy is only a drowning boy, even if once he flew. He knew that spring arrives no matter who died in winter, that an unploughed field goes fallow fast. He knew that we live our lives in the face of marvel and tragedy alike. The corollary of each human life being as full and complete as our own is that our own lives are, similarly, necessary.

Arthur Miller, on a more prosaic and landbound Icarus, wrote:

He's a human being, and a terrible thing is happening to him. So attention must be paid. He's not to be allowed to fall into his grave like an old dog. Attention, attention must finally be paid to such a person.

He was right—we must pay attention—and he was right that attention has a price. To acknowledge in full the suffering of others is to walk a precipice, beneath which an abyss gapes like the mouth of a drowning boy. If we paid no attention, we would not be human. If we left the field and the rod and the crook, we would not be human either. All we can do, in the end, is try to pay just enough attention, to not miss Icarus darting past us at the edge of our vision, to try to extend a hand to as many as we can, should they drop into the sea. To pull back before we drown. And hope that somewhere, should we be devoted enough to stanch as much suffering as we each can without driving ourselves mad, that somewhere a marvelous boy will build new wings.

Add a comment: