The Return of Paul Manafort, Thug Whisperer

The return of Paul Manafort, as reported this week by the Washington Post, marks a stunning turnaround for one of the most shamelessly corrupt figures in modern American politics. This is a man so disreputable that he was fired from Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign after it was revealed that he'd received “$12.7 million in undisclosed cash payments” from a pro-Russian political party in Ukraine. A man so underhanded that he shared confidential polling data with alleged Kremlin associates. A man so compromised that, according to a 2020 bipartisan Senate report, his "presence on the Campaign and proximity to Trump created opportunities for Russian intelligence services to exert influence over, and acquire confidential information on, the Trump Campaign."

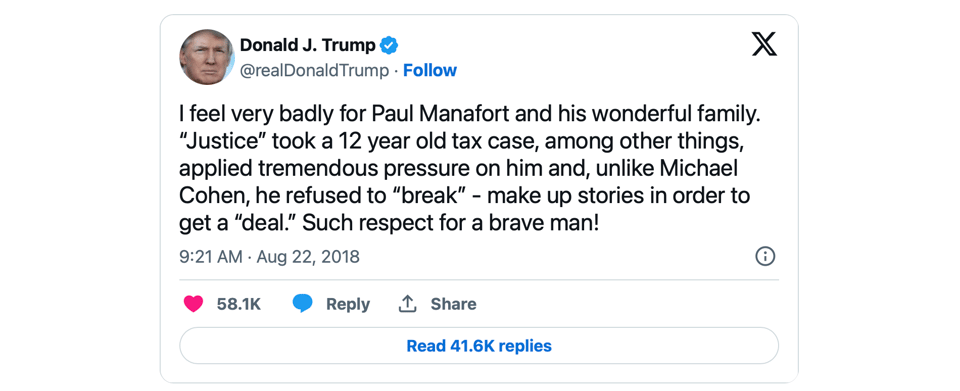

Before he was fired as Trump's campaign manager, Manafort helped facilitate what Robert Mueller called Russia’s “sweeping and systemic” corruption of the 2016 election. After he was fired, he conspired with some of those same associates to help pro-Putin forces return to power in Kyiv. But by 2018, Manafort's luck had seemingly run out: he was convicted of fraud, and "sentenced to a prison term of seven and a half years, to be served at the Federal Correctional Institution Loretto, in Pennsylvania, as Inmate No. 35207-016." He painted a terrifically sorry portrait—confined to a wheelchair due to gout and gray—but in the waning days of the Trump administration, he finally received his pardon. Not so ironically, Manafort had been found guilty of behavior not unlike what the Trump Organization has been accused of: falsifying financial records to secure loans, and hiding those ill-gotten gains from authorities. Now, despite a breathtaking campaign of crooked behavior, Manafort is seemingly back in Trump’s good graces—though you shouldn't expect to see him on TV:

"For decades, Manafort gave guidance to murderers around the world," Talia wrote for the Village Voice in 2018, just as Manafort's trial was coming to an end. "It was only in America, the country that had shaped his tactics, that he found a partial comeuppance." Even though the Russia's invasion of Ukraine was several years off, Talia's column connected Manafort’s role with the Trump campaign to the events of the winter of 2014, when Ukraine’s pro-democracy “Maidan” movement toppled the country’s Putin-approved president, Viktor Yanukovych, whose political career Paul Manafort had been steering since 2004. (We've reprinted that essay below.)

The tenth anniversary of Maidan passed last month with barely a mention in the Western media, but its reverberations are still being felt: in Putin’s "Potemkin" reelection this week; in the unceasing war between Russia and Ukraine; in the 2024 U.S. presidential election. With Donald Trump facing an existential threat to his finances, the return of Manafort to the fold should concern us all. Trump needs money, and now he’s bringing in a man notorious for funneling pro-Putin resources through illicit channels. As Heather Cox Richardson noted yesterday, “Manafort is a whole factory full of red flags.”

Why bring back a someone with such a wretched reputation? For one thing, fucking over Ukraine seems to be near the top of Trump's priority list, and no one knows fucking over the Ukraine quite like Manafort. But there'e also the question of payback. "Trump has told advisers that he feels loyal to Manafort because he served prison time," says the Post's Josh Dawsey. In the former president's mafia-fantasia world view, loyalty trumps all, and the return of Manafort may simply be a way to repay a good soldier.

According to Kost Bondarenko, one of Manafort’s Ukrainian associates, “Trump won because of Manafort” in 2016, and their reunion may have as much to do with winning in 2024 as it does with settling old debts. A decade ago, Manafort was down and out, and then the Trump campaign offered him a lifeline in exchange for his very particular set of skills. Six years ago, he was down and out once more, before Trump came to his rescue with a pardon. For both men, the stakes in the 2024 election couldn't be much higher: their freedom and livelihoods may hang in the balance. Of course, for the rest of us, with the rising threat of fascism and the survival of democracy on the ballot, the stakes are even higher.

— David Swanson

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription.

Paul Manafort Is Going to Jail. But in Ukraine, He Has Left Ghosts in His Wake.

By Talia Lavin

The Village Voice, August 24, 2018

On the morning of February 24, 2014, hundreds of Ukrainians streamed through the doors of the famed presidential palace of Mezhyhirya. The billion-dollar residence, finished in wood, as if to mimic a rustic cottage, was propped up by incongruous white columns; the crowd that flowed between them was witnessing, for the first time, the uses state coffers had been put to under the corrupt guidance of their ousted president. Viktor Yanukovych had fled overnight, vanishing into the depths of Russia, and his guards had deserted their posts. They had watched over the estate, its garages filled with luxury cars, a scale-model Spanish galleon bobbing in the manmade pond, on which Yanukovych had hosted guests for luxurious dinners, with sturgeon caviar served in golden dishes and libations from cellars stocked with priceless brandies; Now the place was left open for a crowd of ordinary citizens, whose average wage was less than $200 a month.

The crowd was awed, but relatively tame. There was no looting, just selfies in the five guesthouses, with the peacocks and pet ostriches and Burmese fowl, on the vast grounds a Washington Post reporter said reminded him “of Marie Antoinette’s idealized peasant village at Versailles.”

Days earlier, on February 20, 48 protesters had died in fierce clashes with Yanukovych’s paramilitary forces, the culmination of a months-long series of rolling street battles centered in Kyiv’s iconic Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or Independence Square—site of the Ukrainian parliament. In 2014, facing pressure from his benefactor, Vladimir Putin, to crack down on civil unrest, Yanukovych had directed riot police to use live ammunition and snipers to fire into the crowd of thousands that had gathered to demand his resignation. The square, with its soaring pillar topped with a golden angel, was scarred with ash and littered with corpses.

It was the climax of Yanukovych’s reign—and its end; he fled three days later, leaving his residence and all its trappings behind, as the protests continued to swell. In many ways, that bloody winter owed its tragic toll to the work of another man, one for whom Yanukovych had been one of many protégés: Paul Manafort.

Manafort began advising Yanukovych in 2004, the year Yanukovych became Ukraine’s prime minister. Manafort’s career had begun decades earlier as a shrewd and unscrupulous young Republican in the 1970s, and his star rose with the establishment of the firm Black, Manafort and Stone, a lobbying outfit Time magazine once dubbed “a supermarket of influence-peddling.” Notorious operative Lee Atwater, a Nixon-style dirty trickster for the ages, joined Manafort and Roger Stone in the business; together, they cleared millions nudging the levers of government on behalf of massive corporations. By the 1990s, Manafort’s appetite for luxury and excitement had outgrown domestic politics, and he turned his gaze abroad. He worked to soften the image of brutal Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos; Angolan guerrilla leader Jonas Savimbi, whose armies committed atrocities and conscripted women into sexual slavery; and Zaire’s infamous Mobutu Sese Seko, among others. The back-channel operations were wildly lucrative; moral lines meant as little as borders to the jet-setting power broker.

Yanukovych was elected president of Ukraine in 2010, under Manafort’s oily guidance; a country that had been the first to break from the Soviet Union, ushering in its collapse, found itself drifting closer and closer to Moscow. The reforms brought about by a popular revolt against Yanukovych in 2004 dissipated under his renewed rule. Activists bridled against the appalling graft of the Yanukovych regime. In a country where women sell dill-flowers by the metro for kopeks, in which more than a quarter of the populationwas living in poverty, the capital was studded with exemplars of Yanukovych’s open corruption. From the long promenade at Mariinsky Park, Kyiv’s loveliest municipal garden, a breathtaking view of the banks of the Dnieper River was marred by the blocky gray bulk of a presidential helipad.

After Yanukovych’s ouster, evidence of Manafort’s activities—and the rich payments he received for them—were pieced together from drowned or half-burned documents in Mezhyhirya and the abandoned offices of Yanukovych’s Party of Regions. Manafort’s name cropped up again and again as the recipient of illicit payments. Manafort’s associate Rick Gates had boasted to friends, “in every ministry, he has a guy” in Ukraine, in what amounted to a “shadow government.” But the ledgers showed that even shadows sometimes leave receipts.

In 2016, investigative journalist and now-parliamentarian Serhiy Leshchenko received one such document anonymously: the infamous “black ledger,” which detailed, in chicken-scratch Cyrillic, some $12.7 million in payments to Manafort from 2007 to 2012. By the time Leshchenko made the document public, Manafort had stepped in to smooth the ascendance of another troubled and amoral politico: Donald Trump.

Manafort is en route to a long prison term now, after a jury found him guilty on eight counts of tax and bank fraud. For decades, Manafort gave guidance to murderers around the world. It was only in America, the country that had shaped his tactics, that he found a partial comeuppance. But in Ukraine—and Angola, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the Philippines—there are bodies in the ground that will never rise again.

The 2014 revolution, known colloquially as “Maidan” or “Euromaidan,” after Independence Square, was led by students and activists; it swelled to become a grassroots movement that encompassed hundreds of thousands of protestors. These days, a war with Russia still rages in the east of the country, as Putin seeks to reclaim by force the influence over Ukraine he once achieved with grease. Some ten-thousand Ukrainians, soldiers, and civilians alike, have died, while 4.4 million have been impacted by displacement, famine, and continual shelling. In Kyiv, the ash has been washed from the cobblestones of Independence Square, and the angel spreads her wings on the top of a pillar that is once again white, presiding over the city’s living and the revolution’s dead.

The ill-gotten mementos of Paul Manafort’s life have been used as exhibits in trial: his stiff legions of suits; his numerous residences; an infamous $15,000 ostritch-leather jacket. Just outside Kyiv, where once-awed protestors touched with hesitant palms the gaudy fripperies of a life sustained on loot, Mezhyhirya remains, unscathed. It’s available for commercial tours, for the curious, but its colloquial name now illustrates precisely what it is: the Museum of Corruption. Perhaps one day, if the era Manafort and his ilk ushered in ever ends, Mar-a-Lago will serve a similar purpose.

Add a comment: