On the Gastronomy of Eating the Rich

Two years before I started a column about the cross-pollination between food and politics, I wrote for GQ about the origins and literal interpretations of the phrase “eat the rich.” It’s survived over centuries because it’s catchy, visceral, gross, absurd, and, at its extremes, radical; class war and cannibalism are two great tastes that go together. Today I’ve revised and updated the piece to reflect a somehow even less buoyant political mood, and my subsequent forays into the under-explored realm of politico-gastronomy.

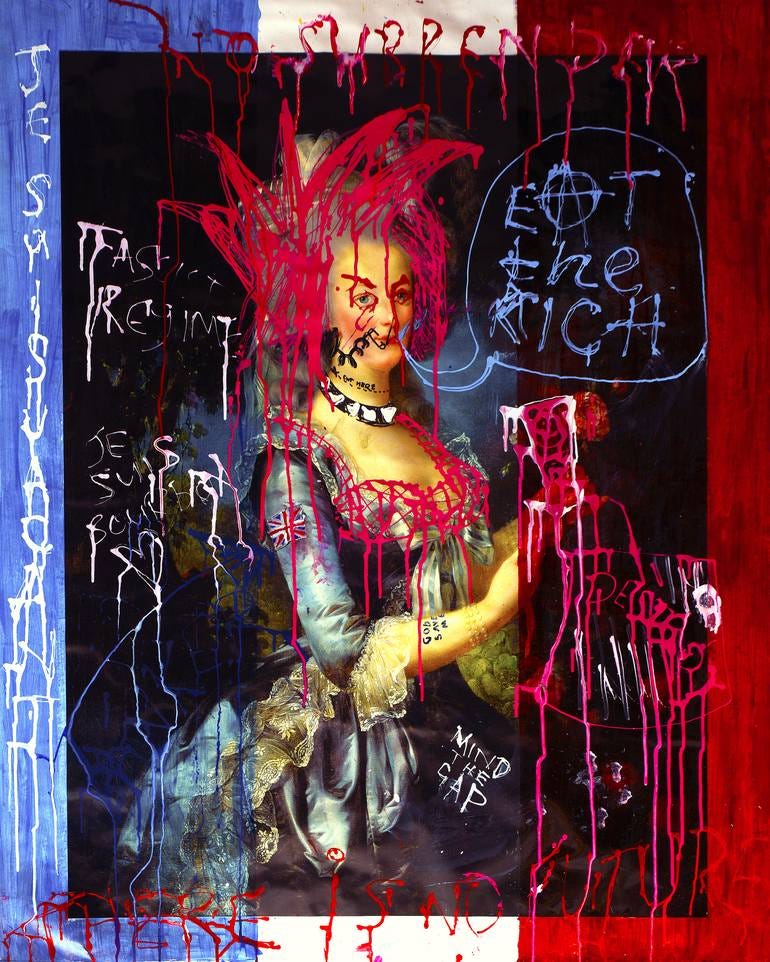

In 1793, the streets of Paris were in an uproar. A few years earlier, citizens irate over poverty, a grinding and brutal famine, and their own disenfranchisement had toppled the monarchy and smashed the Bastille fortress, sending shock waves throughout Europe and the world. It was a transitional time of declarations and riots, blood spilled, and unchecked, revolutionary hope—and a new, more equitable form of government was blossoming into being in the capital. But years into the new order, the people were still restive and unsettled: the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen may have been passed by the National Assembly, and the king himself executed by guillotine, but there still wasn’t enough food to go around.

With the monarch bloodily dispatched, the people had found they could eat neither rights nor freedom, and lacked sufficient bread to enjoy either. Citizens complained that speculative merchants were selling moldy bread, adulterated wine, and diseased, blood-bloated meat to the poor, saving their best wares for the wealthy. In response, according to early historian of the French Revolution Adolphe Thiers, the famous social theorist Jean-Jacques Rousseau delivered a speech to the Paris Commune with a phrase that would become immortal. “When the people shall have nothing more to eat,” quipped Rousseau, “they will eat the rich.”

Two hundred years later, Rousseau’s bon mot still resonates; on social media, in the streets and in our secret hearts, the carnivorous id of class struggle is surging up again to prominence. It’s no wonder that Twitter wags and street protesters are embracing the guillotine aesthetic; America feels frayed by its own striation. While adulterated wine might not be our biggest problem as a society, the country has a very real crisis of hunger simmering in our cities and towns; some 41 million Americans lived in food-insecure households in 2022, according to the most recent data released by the USDA,including millions of children. Scenarios more Dickensian than Jacobin are playing out in schools as a result; in 2019, one New Jersey school district barred students with more than $75 in school lunch debt from attending prom, field trips, and extracurricular activities, then denied a local donor the opportunity to pay down the entirety of students’ debt.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

As is all too common in America, the up-by-the-bootstraps myth that austerity and punitive policy in the face of poverty will lead magically towards abundance held sway in New Jersey. The school district’s superintendent, Joseph Meloche, told local media that “Simply erasing the debt does not address the many families with financial means who have just chosen not to pay what is owed.” The idea that children should suffer in school for either the neglect or poverty of their parents feels cruelly airlifted from another era, one in which the bootstrap was more commonly used as a lash than a metaphor.

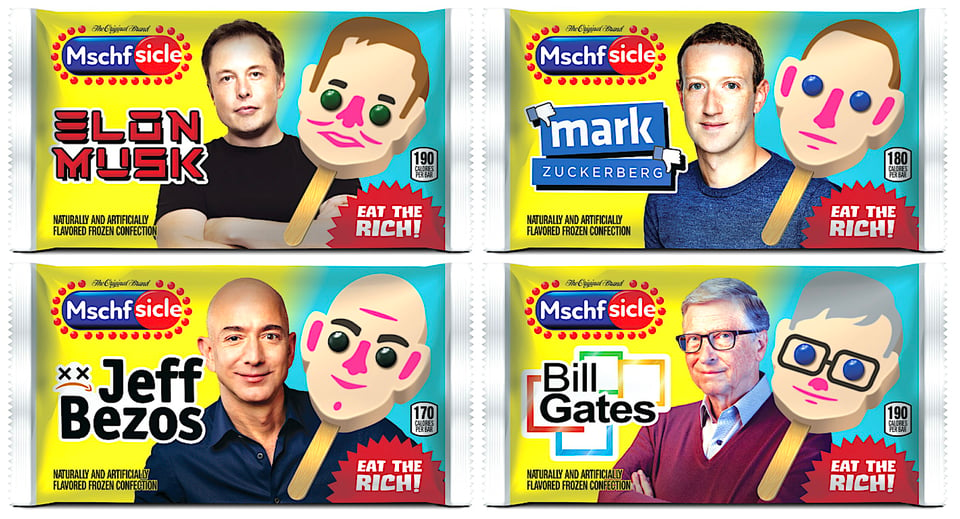

Meanwhile, it seems as if the outlays of the wealthy are getting more and more recherché. Social media has long appealed in part because of its ability to show us the rarified world of fabulous wealth and abundance. But as Texas’ ERCOT energy corporation pays bit-coiners millions not to mine during a heat wave, and New York brutally slashes its public-library budget, it’s hard not to feel the sting of class resentment. America has the feel of the twilight of empire, the frail-boned gerontocrats complemented by the weighty jackboots of a police state. Meanwhile, the super-wealthy oligarchs acquire more and more, and become baroque in their decadence: space tourism, immortality-chasing elixirs, the grotesque Tesla Cybertruck, not to mention the infamous imploding submersible.

It’s no wonder, then, that the digital generation has developed a stewing contempt for 1%, and taken that to social media. The TikTok hashtag #eattherich has spawned millions of videos, which abound with a nascent class-based resentment sprung from the pages of Marx and into meme-ready soundbites. One creator suggests learning to cook wild boar before the class war, because of its purported similarity to the taste of human flesh: “You can be that bitch with the chainsaw, doing all the cooking.” Another professes her desire to “vore” Jeff Bezos, using the Internet slang word for fetish-inspired cannibalism. In yet another video, a teenage girl in a black hoodie performs a signature TikTok maneuver—using progressively appearing snippets of text—to point out that “the only minority destroying America is the rich.” On Twitter, there are countless posts not just urging the eating of the rich—but asking for, or providing, recipes. (“Simmer £100,000 cash in the blood drained from the carcass. Serve on a bed of rocket with a side of coleslaw.”)

In prior periods of excess, Rousseau’s enduring quote has resurfaced to spice up cultural artifacts. Most entertainingly, the greed-is-good ‘80s gave rise to the 1987 movie “Eat the Rich,” with a title song by Motörhead, the mesmerizing trans actress Lanah Pellay in a lead role, and some truly visceral scenes centered around the minced meat of the wealthy, eagerly consumed, with French fries, by their monied peers. (Most of the major action scenes involve bows and arrows, Lemmy from Motörhead actually plays a KGB agent sent to sow class dissension in England, and the would-be Prime Minister is a crude, belching blonde guy who flirts with fascism; it’s the kind of movie that makes you wonder if you’re on hallucinogens, or if the writers were.) In the overconfident, imperial bloom of the early ‘90s, Aerosmith made their own sally into class warfare, and their song “Eat the Rich” has surprisingly literal lyrics. “With this here fork and knife/Eat the rich/There's only one thing that they are good for,” yowls Steven Tyler, wearing a pair of devil horns.

These days, politicians are largely ignoring an increasingly belligerent national mood in favor of sating their customary hunger for big-donor largesse. For Rousseau, the notion of eating the rich was a Swiftian exaggeration of the struggles of the starving masses, in response to a quite literal famine that was the French Revolution’s most proximal cause. In memes and on social media, “eat the rich” is a slogan that serves as both a signifier of class struggle and a play on literal consumption of the flesh of the wealthy. On Etsy, you can buy “Eat the Rich” dinner plates; on Redbubble, a customizable merch site, there are countless items for sale with the slogan, and several have replaced the hammer in the hammer-and-sickle of Communism with a fork. In some ways, “Eat the rich” is the perfect revolutionary slogan for the digital era: it’s succinct, easily shareable, and built for risqué humor. It’s hard to get edgier than cannibalism, and no would-be Internet humorist worth their salt can resist the lure of a Bezos bulgogi. But for all the waggishness of the slogan, revolution is usually born of an authentic powerlessness and privation; it’s hard not to feel, these days, that the American populace abounds in both.

-

Talia, there is a fact-checker problem in this lovely piece, which is that Rousseau died in 1778, and hence if he recommended eating the rich it was at some other historical moment than 1793. Just sayin.

-

Further research suggests that Thiers did not say that Rousseau said this in 1793, just that he said it at some time or other, but it looks like the quote ("Quand les pauvres n'auront plus rien à manger, ils mangeront les riches!") is completely bogus, and Thiers just made it up.

Add a comment: