On Cults, Part 2: Follow the Leader

What’s the loneliest you’ve ever felt?

The most scared? The most despairing?

Was it a period of depression, or scarcity, or grief? Was it a sense of isolation? A sense that nothing would ever get better? A sense of total purposelessness? A nagging, worming anxiety that wouldn’t let you rest?

Was it all of that? Was it more?

What if there was a group that would treat you like a family member—provide you housing, an instantaneous community of many brothers and sisters, aunts and uncles, surrogate parents and children?

What if you could, just for a moment, or forever, lay down the burden you’ve been carrying so long, all the countless high-pressure micro-decisions you have to make in a day? What if you felt that the people beside you understood, really understood, just how hard it is to make it in this world—just to keep your head above water? What if you witnessed miracles? What if you felt genuinely and truly accepted for the very first time in your whole life? What if someone was speaking and you trusted them—really trusted them—enough to lay that burden down at their feet, and let go into lightness?

Thinking about cults (as I have been nonstop lately—it’s cult month here at The Sword and the Sandwich), I’ve been struck by their mechanics: the way they always seem to have a charismatic leader, or circle of leaders; the way the flock follows them ad extremis; and why people are drawn to these high-pressure, high-control groups.

Reading Waco Rising: David Koresh, the FBI, and the Birth of America’s Modern Militias; The Sullivanians: Sex, Psychotherapy and the Wild Life of an American Commune; Raven: The Untold Story of the Reverend Jim Jones and His People; A Billion Years: My Escape From A Life in the Highest Ranks of Scientology; and Pilgrim’s Wilderness: A True Story of Faith and Madness on the Alaska Frontier, as I have since writing part one of this column on cults (plus some other unrelated books; I mean, I’m not a total weirdo), got me thinking about charisma and its attractions, in all sorts of different contexts.

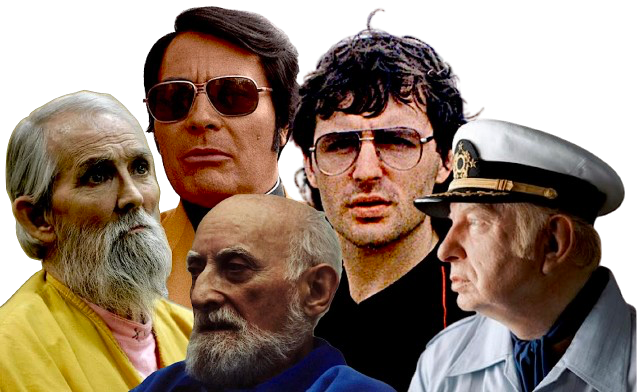

Jim Jones came out of an impoverished boyhood in Indiana, where he killed animals, idolized Hitler, and quoted scripture. The Sullivanians were a group of predatory psychiatrists in godless New York City, led by an antifascist Jew (and sexual predator) named Saul Newton. Scientology was founded by sci-fi writer L. Ron Hubbard, a man obsessed with the sea, immortality, and aliens. The Pilgrim family cult arose in the mountains of New Mexico and migrated to Alaska. Some of these groups have roots in Christianity (although the Sullivanians emphatically didn’t); many took up the mantle of the ‘60s and ‘70s counterculture. Some preyed on the founders’ own families; others captivate hundreds or thousands. Some—like the multi-level marketing companies in Jane Marie’s Selling the Dream: The Million-Dollar Industry Bankrupting Americans—started with a sales pitch, and wind up taking you for all you’ve got, including your relationships, your reputation, your identity.

I’ve studied hate groups, too, up close and personal, and this all got me thinking about what we think about when we think about cults. It’s very easy to sneer at people selling essential oils, or chrystals, or, the archetypal example, “drinking the Kool-Aid” at Jonestown (let me be likely not the first to tell you that that was an act of mass murder, not mass suicide, with the poison administered at gunpoint). It’s easy to wonder what the hell David Koresh’s many wives were doing up on Mount Carmel near Waco—or, more to the point, what their legal husbands were thinking in allowing their very young daughters or longstanding spouses to “marry” a prophet (polygamous marriages are, of course, not recognized by the law). It’s all entirely valid! These are not good things to be doing! They are even dangerous, or stupid, or cruel, or fanatical! Parents exiled from their babies, rape and incest normalized, financial ruin, mass death—these are terrible things that people do, driven by faith.

And yet.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

I think about how lonely I’ve been sometimes. How deeply, gnawingly anxious. How much the forever not-knowing if I’m doing right wears at me; how I lie awake at night wondering if I’ve fucked up my life forever, if some long chain of decisions starting in my teens led me to a dead end. I think about times I’ve lost friends or relatives, times I’ve just wanted any kind of surcease.

Part of looking at cults honestly is realizing that with the exception of a very few innate skeptics, most of us, at some point in our lives, would be susceptible to such a pitch, if it harmonized with our greater values; if it came at a point where we felt low, and frightened, and individuality felt like more of a burden than a sacred thing to uphold. When we wanted to be embraced, upheld, nurtured, instructed. All of us have felt that, whether we knew to articulate it or not.

There are cults that fit different sensibilities: the liberal aesthetes of New York City, including several leading lights in the Abstract Expressionist movement, got caught up in the Sullivanians’ twisted therapy; they talked about finding “an instant community,” a kind of paradise in scrappy ‘70s New York. L. Ron Hubbard took advantage of the scientific fervor of the Space Age, and promised miracles in body and mind for his disciples—spiritual and physical healing for those who craved it, an elevation beyond even prosaic humanity. The Peoples Temple started as an interracial congregation in the 1950s, when churches were famously the most segregated institutions in America. Koresh’s Branch Davidian followers were also racially mixed, and when he preached, he knew the Scriptures inside and out, could light them up with a kind of holy fire that left you entranced, left you feeling like you had clued in to the deeper meaning in life, that you had a purpose. You mattered. Someone else—someone everyone around you looked up to, adoringly—was telling you that you mattered, you meant something. What you gave up, in return, was freedom: something, perhaps, you felt you’d squandered in isolation and uncertainty, in wandering and in shame.

Tell me you’d never join a cult and I’ll tell you you’ve been lucky. That the savviest representative of the most appealing group didn’t reach you on the worst day of your life. In your thirst on your lonesome road, no one offered you water from a poisoned well.

Still, while we may all be susceptible, on the wrong day, to the right pitch, I look at the thrust of our contemporary politics, and see the echoes of the ideological control that thrums through these groups. One telling fact, to me, is that there have been, for some years now, a group of Trump-rally die-hards: they treat these inchoate, xenophobic ramblings as a kind of Phish show or Grateful Dead tour. They wear the merch—MAGA hats and T-shirts—and follow him around the country. They know each other, and bask together in what feels, to them, like a festival. Like belonging. Some have been to forty rallies; some fifty; others five, or six, or ten. They travel cross-country to be first or second in line. They wait, and meet, and bask in proximity to the person who tells them who they are. Who says he needs them. And if they’ll trust him, he’ll make things right. He’ll take up that burden for them, the burden of individuality, and subsume it all into his enormous, gaseous cloud of ego; all that tremulous wanting and waiting and confusion need never trouble them again.

Because Trump, for all his flaws, is charismatic—a kind of Borscht-Belt-meets-televangelist style of speaking that mixes florid, Florida, and his native Queens. Yes, there may be long, rambling asides about his fixations, like hairspray, shower pressure, and sharks, but he knows how to take hold of a crowd when he needs to, how to lift them up in an orgy of hatred. There’s a ritualism present in his rallies that is not unlike an altar call at a megachurch; he’s about one step from the faith healing Jim Jones practiced in his early days, smuggling in animal innards to willing dupes who’d say they’d passed cancerous growths due to his touch.

His message is repulsive; it’s one of hate, of the stripping-away of human rights. It would reduce women to animals in this country, would induce a wave of mass deportations that would cause unimaginable torment. It would be the end of democracy as we know it here in America—the end of choice.

To some people, though, the end of choice is a relief from suffering.

I’m not advocating for pity or understanding of these people, nor reconciliation; it’s more that they are not alone in choosing to follow a leader to the end, beyond all sense and use, beyond catastrophe. That their fanaticism is not so easily dislodged; that in this ideological movement, which demands a kind of lockstep, rigid behavioral code among its adherents, they have found the sweet peace of surrender, and that is something difficult indeed to dislodge. As such the diehard Trumpists must be approached as believers, with all the irrationality, and the zeal, and the passion—and the identity—of faith.

Ask yourself: what’s the loneliest you’ve ever been? What would you do to make it stop? And what would you do if someone tried to take that away from you?

And there you have an answer for what we’re confronting. And from that recognition comes the power to fight back; only with knowledge of the scope of the threat can we begin to approach it. To recognize zealotry for what it is, and win our way back to the freedom that can be so heavy, but all the same needs lifting, knowing we must put our shoulder to the wheel.

-

A good friend of mine was at a bit of a low point in his life, and was befriended by a couple of people in London one day, and drawn into their community... and it was a while before he realized they were Scientologists and what was happening to him. Luckily, he was able to extricate himself before things got too serious, but I remember thinking "Wow, if it can happen to a smart, independent achiever like him..."

I've never felt much need for a "community" or to "belong" but I look around and the world right now is about as depressing a place as I can ever remember (I'm nearly 62), and I've several friends fall down the right-wing and/or conspiracy theory rabbit holes, and I can see how they feel comforted by the communities they find there. It's scary.

-

Lauren Hough actually talked about that a lot in her memoir about the children of god cult and how they preyed on lonely disallusioned college age people. its one of the things i really liked about her book was how she treated the people who joined with like grace really. even though she went through a lot because of literally being born in it. that if you're lonely or depressed and these people come along and offer you unconditional love and then a cause and how good it feels. she also talks about how a lot of women then get trapped because now you have kids and literally what are you going to do now? Sorry I got kind of obsessed with cults for ahile and that was probably my favorite book about them because she talks a lot about the effects later on.

-

I've been a (free) reader for awhile but felt moved to comment this time because I think you've landed on something important here. I've been on the edges of a few groups in my time that I later recognized as cults. There's a vibe to them you can't mistake once you know it, and when images started coming out from early Trump rallies there was a stomach-churning familiarity to them.

Add a comment: