Notable Sandwiches #99: Kabuli Burger

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the series where I drag my long-suffering editor David Swanson through the bizarro, shifting sands of Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week, a dish made famous in Pakistan by Afghan refugees: the Kabuli burger.

"Go home. These are our mountains. We'll work things out for ourselves."

—Afghan shopkeeper to Soviet soldier, Zinky Boys (1992)

For the majority of my life, the US was at war in Afghanistan. Twenty years—an unfathomable length of time for a modern conflict; sons went into the same war their fathers served in—and it is hard to contend that anything was gained, or even learned. And so much was lost. An ocean of lives, whole villages and communities. One country destructively at ease with both permanent war, and with exiling that war to the furthest corners of our minds, a militant doublethink that became our nature. A second country, scarified by omnipresent war.

In 2017 the U.S. Army dropped the “Mother of All Bombs,” the GBU-43 MOAB, the most destructive non-nuclear weapon in its arsenal, on Nangarhar Province in Afghanistan. It was a year into Trump’s presidency, and while, nominally, it was a strike against militants in the region, it seemed to be done just for the hell of it. Shock and awe. Pure military-industrial theater. The cloud of black smoke rising above the desert like an inkblot, like a Rorschach test of our national madness. The strike made about as much sense as anything else by that point, although the war would not end for another five years.

There's something surreal even in reflecting on that war: the way it was so remote, and yet so present; the threads of patriotic militancy that weaved through and remained within our national consciousness; the constant reminders to revere the sacrifice of the troops, who were sacrificed over and over and over for two decades. The way it still doesn’t feel quite real that it ever ended. Outpourings of propaganda surrounded its beginning and continued throughout its course; at first, it was seditious to question, and then the grinding ceaselessness of the conflict made protest seem futile. But the war did end. What’s left behind? Only scars. Only the desert. Only the mountains. Only the lost. Sand stays sand no matter how much blood it absorbs.

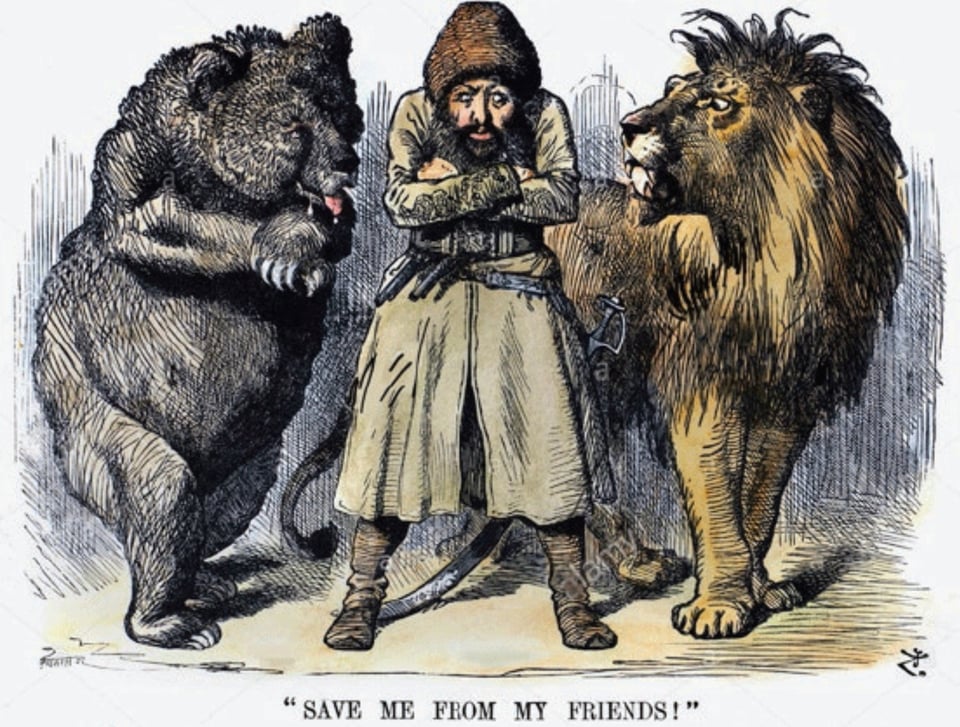

What makes the story even more extraordinary is the war that preceded it. It’s a cliché by now to say that Afghanistan is the graveyard of empires; in the nineteenth century, Britain and Russia fought three separate wars in “The Great Game” for control of this land-locked tract of mountains and desert. A century later, the Soviet war in Afghanistan, a nine-year conflict that lasted throughout the 1980s, hastened the decay and end of that empire. It also displaced millions, killed millions more, left millions wounded in body and spirit beyond recognition.

The Belarusian writer Svetlana Alexievich1 chronicled this conflict in a masterly tapestry of remembrance published in 1992. Its title is translated as Zinky Boys, or Boys in Zinc, after the sealed zinc coffins in which mutilated casualties were shipped from the front back to their relatives. The book is, like all of Alexievich’s work, harrowing and astounding. “War is a world, and not an event. Everything here is different: the landscape, a human being, words,” she wrote of her time reporting from the frontlines in 1986. “It is a human right not to kill. Not to learn to kill. A right that is not recorded in a single constitution.” (The year the book was published, Alexievich was put on trial by the Belarusian state for “slandering the heroes” of the war, though she used their own words almost exclusively.)

The language fed to the Soviet servicemen is hauntingly familiar. In Alexievich’s work, there’s a steady, authoritarian drumbeat reinforcing the necessity of safe borders, patriotic duty, and international goodwill. Authorities claimed to be building bridges and schools, and providing medical care to an impoverished Afghan populace. But no one builds anything in these pages. The Red Army leaves villages razed like plowed fields. Skulls break, viscera break, people break. They stay broken. Death in wartime provokes dissociation, she wrote; it is “ludicrous and gratuitous.” “A human being should not be subjected to trials like this,” she wrote. “A human being cannot endure trials like this.”

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription.

Of course, Alexievich—as a Russian speaker and chronicler of Soviet history, interviewing Soviet fighters, nurses, and relatives—views Afghan civilians from afar. As corpses. As vendors hawking black-market wares to dispirited soldiers, who trade bullets for candy and are shot by the same bullets. As the enemy, or the dead, or embittered strangers. Even a soul as transcendently human as Alexievich is unable to dissolve the dual barriers of language and violence. Afghan writers like Jamil Jan Kochai, Khaled Hosseini, and Nadia Hashimi have ably stepped into this gap, writing from, and about, a country to which empires seem irresistibly drawn. They write about joy and endemic violence, for international audiences. None of them live in Afghanistan anymore; two of them were born refugees or immigrants, their parents having fled invasion before they were born. Mass displacement is also a face of war, the necessary acts of flight and survival, the part of a populace forced to remake life anew, produce the fruits of that life elsewhere.

It was in such a state of displacement that the Kabuli burger, also known as the Afghani burger, was born, created by refugees from the Soviet war who fled to Pakistan. As with many of the sandwiches on this list, its precise origins are difficult to pin down, but the general consensus as to its community of origin, and its general form, are fixed. The burger, which is not strictly speaking a burger (even loosely speaking, it’s not really a burger), has become a beloved and ubiquitous street food in Peshawar and Islamabad. It is made of Afghan roti wrapped around garam-masala spiced french fries, various sauces and chutneys, and usually an assortment of meats, such as sausages or kebab or meatloaf. From the teeming Afghani refugee camps, the sandwich spread across Pakistan, a cheap, tasty, filling treat sold at food stalls all hours of the day. Today, Pakistani news sources claim that, despite their best efforts, locals have been unable to successfully reproduce the delicacy—even after mass revocation of visas forced many of the original burger-makers back to Kabul.

None of which explains why this particular sandwich is called a burger. It's a wrap whose primary ingredient is French fries. Why should its moniker be taken from an American staple named after a German city, and, for that matter, filled with Franco-Belgian fried potatoes alongside masala chutney and halal chicken sausages?

Then again, why should any of this make sense? War doesn't. Mass displacement doesn't. If war is a country, as Alexievich contends, it doesn’t have any borders at all. It is the universal thing, the recurrent and central thing, the ouroboros that wraps the world. Why should it contain anything at all, produce anything imaginable? The pain and deprivation it engenders has no end. Neither do ingenuity and survival. Nine years of war, and then, from another empire entirely, twenty—in the same country. Make that make sense. You can't. Give that time back. You can't. Unseal the zinc coffins. You can't. Undig the graves, return the souls to their houses. You can't. All you can do is take warm bread and fold it in your hand around a meal that is hot and nourishing and immediate. All you can do is survive, and not be erased.

“During a bombardment you beg (who you’re begging I don’t know; you beg God): ‘Let the ground open up and hide me. Let the stone part,” one soldier told Alexievich. In her own notebooks, she wrote: “I shall return from here a free human being. I wasn’t one until I saw what we are doing here. It was terrifying and lonely. I shall return and never go into a single war museum again.”

1 I was introduced to Svetlana Alexievich when fact-checking Masha Gessen’s profile of her in the New Yorker, after she became the first journalist (or oral historian) to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. As the only Russian speaker on the article’s fact-checking team, I spent hours on the phone with this legendary person, and she was incredibly kind, if somewhat bemused by the whole thing. One detail—incidentally, food-related—stood out from the process: in describing the work of one of her mentors, a writer who chronicled the Siege of Leningrad in an oral history whose form she would master, she mentioned the story of a boy driven so mad by hunger he contemplated stealing half a meatball from his neighbor. I found the book, and scoured it for the story. Reader: it was not half a meatball the starving boy contemplated stealing; it was a potato. But in the context of an article about memory and oral history… and given our awe of Alexievich… and the fact that she gave the great quote “Don’t put yourself next to the meatball. You’ll lose,” we didn’t say anything. How could we? I both wish and don’t wish that I had corrected her.

-

An Afghani "chip butty" sounds very tasty!

Add a comment: