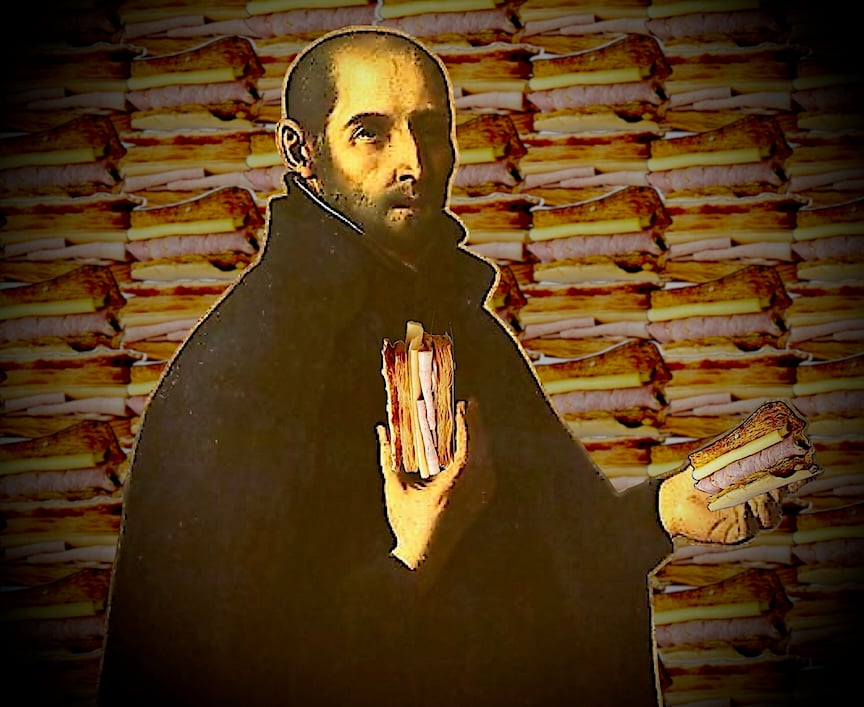

Notable Sandwiches #95: Jesuita

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where I and my longsuffering editor David Swanson stumble our way through the strange and mutable document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches. This week, a South American delicacy: the jesuita.

Do you ever learn a word, or an idea, and suddenly start seeing it everywhere? Like you’ve just picked up a nifty bit of vocab like “susurrus” and then it appears in the next book you read, and the next, or someone mentions it to you, and it feels—not logically, like you’ve assimilated the word or concept and thus are more prone to notice it where otherwise you might have simply ignored it, but like a sudden shift in the world, a slide forty degrees to the left, where this new thing is present in your life all the time—a little bit magical or strange or sinister?

That is more or less how I feel about ham and cheese sandwiches since I’ve started writing this column. Call it the Baader-Meinhof Monte-Cristo Effect: ham and cheese sandwiches just keep coming up, as if they are the true and inevitable archetype of a sandwich, proliferating in different cultures (although the French are overrepresented). What changes? The terroir of the ham, the style of bread, the size or shape, but at its center is still, well… a ham and cheese sandwich. I didn’t grow up with ham and cheese sandwiches, and my kosher-keeping parents are somewhat miffed that I keep writing about them (though I do not control the List). Still, they keep returning, to the point where I had felt I had exhausted my ability to even write about any conjunction of starch, pork and aged lactose of any kind.

Until I met the jesuíta, a product of the complex tradition of Portuguese pastry, and a profoundly weird iteration of this particular genus of sandwich. It is a dish that sounds at once baffling and tantalizing. In its original form, as served by Pastelaria e Confeitaria Moura in Santo Tirso, a gorgeous little city north of Porto, the jesuíta isn’t even a sandwich.

It’s a little triangle of puff pastry topped with meringue. Pastelaria e Confeitaria Moura has been serving these by the thousand for a hundred and forty years, and the hunger for them migrated along with Iberian imperial ambitions. As a sandwich, with the incongruous addition of ham and cheese, it’s become a favorite of Uruguayan and Argentine cuisine (in the former, the sandwich is still called the jesuita; in the latter it’s called a fosforito, or matchstick, rather than its ecclesiastical moniker), and has colonized other countries in South America, bite by sweet-and-salty bite.

Variants of the pastry exist around Europe, too: in France it’s a jesuite, filled with frangipane; in Germany, a Jesuitermützen is full of custard. Only in meat-happy South America did they decide to stuff the mini-churchmen with savories, the meringue having deflated to a royal icing glaze.

But having answered the what, I’m left with so much why! Why is it named after the Jesuits? Why stuff iced puff pastry with ham and cheese? Sources on the jesuita are frequently befuddled by the subject (one reference on the Wikipedia entry is entitled “El misterioso origen de los jesuitas”), although there are two somewhat dubious theories about the name. The first is that Jesuit robes kind of look like triangles—and some Portuguese forms of this weird petit-four has a blunt rather than pointed top, perhaps a nod to the Jesuits’ flat caps. I don’t reject this idea outright, but it’s kind of suspect; a lot of things look like triangles, and a lot of things are more triangular than robes, including, well, triangles, a perfectly viable name for a pastry. The Jesuits have been mostly well-received in Portugal, with a particular efflorescence in the 1500s and 1600s, and subsequent withering in mid-1700s, when they were expelled from all Portuguese territories. But why this intimation of cannibalism? Who wants to eat a Jesuit? What’s the deal?

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription.

The second reason to connect Catholicism and pastries is a backbone of Portuguese baking; apparently, monks, priests, and nuns used to starch their clerical habits with egg whites, leading to a surfeit of egg yolks in the vicinity of monasteries and convents. This surplus led to the invention of the absolutely delicious Portuguese egg tart, or pasteis de nata, which emerged in the 17th century in the Hieronymites Monastery in Lisbon. In 2011, pasteis de nata were voted one of Portugal’s “Seven Wonders of Gastronomy”, alongside caldo verde, grilled sardines, and a garlic sausage invented by Jews attempting to mimic pork sausage to avoid the Inquisition in the late fifteenth century.

At any rate, the egg-white thesis explains the yolky egg wash on the jesuita, and Santo Tirso is perhaps most famous for its enormous and ancient monastery, dating back to 1097, so there may have indeed been a religion-based yolk surplus leading to innovation in sweet pastry… but Santo Tirso is Benedictine, and has been for centuries. Why name your pastry a jesuita in a Benedictine town? Why are triangular sweet pastries named after Jesuits all over Europe, in fact?! I’m writing this at 3am so the question is starting to feel really weirdly urgent and I can’t figure it out, and it turns out googling Jesuits too hard can lead you down some very weird rabbit holes.

There are a lot of conspiracy theories about Jesuits—and the order has a very real history of persecution, being scapegoated and suppressed by various kings in various European countries over the centuries (including in Spain and Portugal). Modern conspiracy theories around the order claim they were behind the sinking of the Titanic (on J.P. Morgan’s orders) and the assassinations of both Abraham Lincoln and JFK (to destabilize American democracy).

This is the destiny of any organized and self-consciously differentiated group, I suppose, although the Jesuits don’t appear to have any more evils to answer for than the rest of the Catholic Church (legion), and perhaps somewhat fewer. Shining bright from this shadow of ignominy is a little triangle of puff pastry, mysteriously named after Loyola’s loyalists and a beloved dish from Bilbao to Buenos Aires. It’s perhaps the most benign of conspiracy theories about the Jesuits, to claim that they secretly named this pastry after themselves for their own enigmatic reasons. But this is the theory I’m going to forthwith invent, and hereafter stick to.

As with so many culinary mysteries, a fog of saccharine myth and quasi-fact has obscured the truth about the jesuita’s etymology; it’s as unknowable as whether Jesuits or an iceberg were really behind the sinking of the Titanic (… just kidding… sort of). What’s certain is that it is a novel spin (for me) on the ham and cheese sandwich, contains egg yolks, and sounds, on the whole, fairly delicious. I’d like to fly down to Uruguay, which has cast off its imperial yoke and filled its jesuitas with ham and cheese, saunter up to the best bakery in Montevideo on a cloudless day, and sink my teeth in. Then I’ll soak up some South American sun, and buy a couple dozen bizcochos to go along with it. That sounds a lot better than my current, rather monkish life in New York, and I will take that dream with me through the week—that far away in a new city people are eating things that are sweet and strange, and in the everlasting someday I may, too.

-

These posts are always a bright spot in my day -- thank you! Also I really want to try one of these, I'm intrigued.

-

"...in the the everlasting someday..." I hadn't heard of this place before this minute, but I live there now

Add a comment: