Notable Sandwiches #94: Jambon-Beurre

By David Swanson

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where we trip merrily through the bizarre and mutable document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week, an iconic Parisien: le jambon-beurre.

The jambon-beurre—like the French flag, the French national motto, even traditional French society—consists of just three elements: ham, butter, bread. The sandwich, also known as Le Parisien, is as emblematic of the French capital as the pizza slice is of New York, though its appeal extends far beyond the Paris city limits: the French eat almost 1.3 billion of the sandwiches each year. What makes such a basic-sounding meal so special comes down the quality of those three ingredients. The ham should be jambon de Paris, a cooked ham, with thin slices carved from a bone-in joint. The butter should be cultured, high-fat, and high quality—the best you can get your hands on. And the bread, it goes without saying, should be a baguette. So far, so simple. But as the great chef Alain Ducasse reportedly noted in regards to the jambon-beurre, “the simpler things can be most difficult.”

As this column approaches the one hundred sandwich mark, the jambon-beurre marks the eighth or ninth ham varietal we’ve encountered. In previous essays, Talia has untangled the knotty legacy of jamon iberico, and its weaponization against Spanish Jews; shared the history of swine husbandry, and the global conquest of the domesticated pig; and written a whole series of ham sandwich essays in the styles of Ernest Hemingway, Charlotte Bronte, Raymond Chandler, and more. As she noted then, “every sandwich is, to a degree, a blank canvas for me, the writer—onto which I project concerns about history, empire, savor, particular incidents of memory, etc. The ham sandwich, which we’ve covered in various forms already—the French croque-monsieur, for example, the Cuban, the Denver, the Peruvian butifarra—is in particular a blank pink screen for projection.”

This week’s version of the ham sandwich is quite the canvas. In his 2012 book, Éloge du mode de vie à la française, the philosopher Yves Roucaute argued that the French way of life was best evoked by the jambon-beurre. With traditional Gallic values threatened by the creeping McDonaldization of society, Roucaute celebrated the virtues of the simple café, and its quintessentially Parisien sandwiches: “By this apparently simple act of buying a sandwich is created a communion around regional products. So with butter, bread and pork, without knowing it, you declaim these three words: 'liberty,' 'equality,' and 'fraternity.’" Inspired by Roucaute, and the French proclivity for things that come in threes, this will be a tripartite endeavor; please forgive any ham-handedness going forward.

Liberté et Jambon

Given everything Talia’s already covered, I don’t have much to add on the ham front, beyond the fact that its connection to France goes back millennia—to the days when the Gauls roamed free, before the Romans took their liberty and sold them into slavery. In the ancient world, the Celtic peoples who populated what we now know as France were renowned for their hams, a legacy that can be tasted today in areas they once settled. As Mark Essig writes in Lesser Beasts: A Snout-to-Tail History of the Humble Pig, “Cato reported that a Gallic group from northern Italy cured 3,000 or 4,000 hams annually for export to Rome. These Gauls lived around Parma, now famous for its prosciutto, which suggests that the region has enjoyed a continuous tradition of ham making for two millennia. The same is true for Iberia and Germany.” If the ham sandwich is really a blank canvas on which we project our experiences, the jambon-beurre’s story is one of quality, simplicity, and tradition. And while you can’t have a jambon-beurre without the jambon, what makes this sandwich something worth savoring really comes down to the simplest components of all: bread and butter.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription.

Égalité et Pain

In a nation which defines itself by food, no foodstuff has played a bigger role—in both French history and identity—than bread, that great leveler. Is there a more evocative symbol of French culture than the baguette, a signifier of sophistication that anyone can afford? There are several predictably apocryphal origin stories for the iconic long loaf, but the truth is fairly prosaic. In Dirt, Bill Buford’s memoir of learning to bake in France, the baguette is the irresistible pinnacle of the boulangère’s art:

“The word baguette means “stick,” or “baton,” the kind that an orchestra conductor keeps time with, and wasn’t used to describe bread until the Second World War, probably—and I say “probably” because there is invariably debate. (There is even more about how to define a baguette: Should it weigh two hundred and fifty grams? Two seventy-five? Do you care?) Tellingly, the word appears nowhere in my 1938 “Larousse Gastronomique,” a thousand-page codex of French cuisine. Until baguette became standard, there were plenty of other big-stick bakery words, like ficelle (string), and flûte (flute), and bâtard (the fat one, the bastard). It doesn’t matter: it is not the name that is French but the shape. A long bread has a higher proportion of crust to crumb than a round one. The shape means: crunch.”

While long loaves did exist prior to the arrival of the modern baguette roughly a century ago, most bread in France was of the round, dense, hearty variety. “The baguette’s creation is the source of many urban legends,” write Catherine Porter and Constant Méheut in the New York Times. “Napoleon’s bakers supposedly created it as a lighter and more portable loaf for the troops; Parisian bakers were said to have made it a rippable consistency to stop knife fights between factions building the city’s subway system (who could rip the bread apart with their bare hands and did not need knives to cut it). In truth, historians say, the bread developed gradually—elongated loaves were already being produced by French bakers in 1600. Originally considered a bread for better-off Parisians who could afford to buy a product that went stale quickly, unlike the peasant’s heavy, round miche that could last a week—the baguette became a staple in the French countryside only after World War II.”

Fraternité et Beurre

The baguette may well be the food that best symbolizes French culture, but butter is the food that best symbolizes French cuisine. And there is nothing that brings people together—that fosters fraternity—like cooking. It is said that the three secrets to French cuisine are “butter, butter, and more butter,” which tracks—the French consume four times as much of it as the average American. As Julia Child famously put it, “with enough butter, anything is good.” The French version has a much higher percentage of fat than what we’re accustomed to in America, and its manufacture is subject to the same rules of terroir that govern winemaking. Butters from Normandy and Brittany, for instance, are made from the milk of cows who graze on mineral-rich sea marshes, giving the final result a distinct flavor profile.

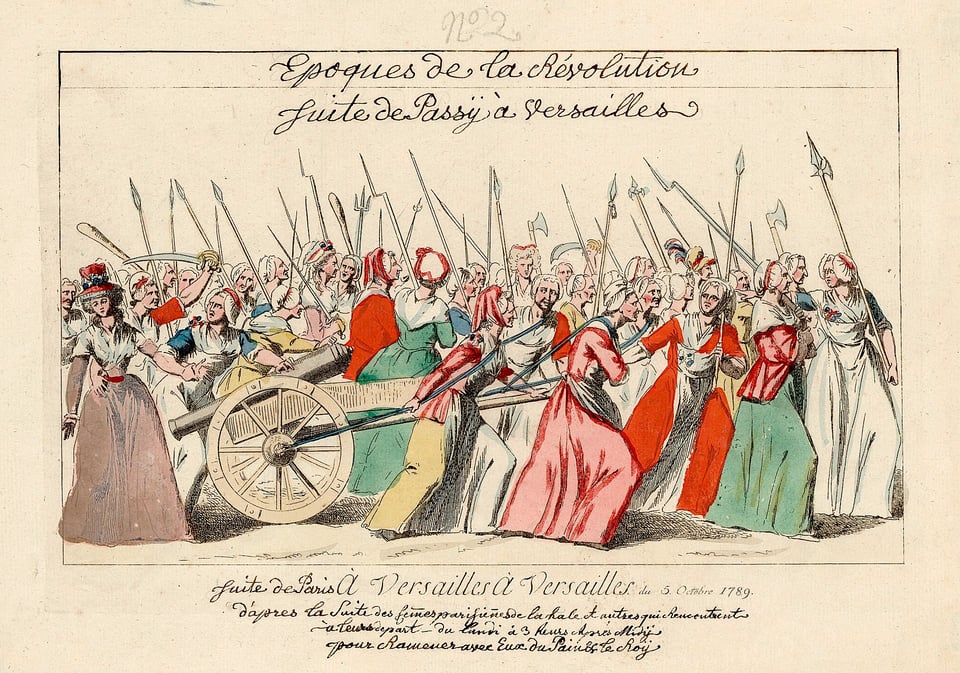

The French association between butter and the simple, pure country life was such that, in the final years of the ancien regime, Marie Antoinette loved nothing more than to repair to her fantasy country village on the grounds of Versailles and cosplay as a milkmaid. The Queen’s Hamlet, with its windmill and dairy and pig sty, was completed in 1787, just two years before a mob of Paris women marched on Versailles demanding bread or the Queen’s head. In 18th-century France, half of a worker’s daily wage went to bread. While it is distinctly unlikely that Marie Antoinette responded to the women with her famously ignorant ”let them eat cake,” the disconnect was unbridgeable. The queen kept her head for another four years.

By the time the queen met her fate at the guillotine in 1793, France had a new three-word motto to go with its three estates and its tricoleur flag: “Liberté, égalité, fraternité,” those three fundamental rights on which modern French society was built—and which Yves Roucaute found manifest in the nation’s favorite three-ingredient sandwich. As it happened, despite Roucaute’s 2012 warning about the rise of fast food, by 2014 hamburgers had surpassed the jambon-beurre as France’s most popular sandwich, a development that was met with horror in certain circles. But if the hamburger is slowly supplanting the jambon-beurre in France, there seems to be some reciprocity at work.

“I am willing to make a case that there’s nothing more luxurious than a jambon-beurre,” wrote The New Yorker’s Hannah Goldfield in 2022. The same year, Florence Fabricant called it “the Proustian ideal of a ham sandwich” in the New York Times. At this point it seems as if all New York’s leading French chefs are getting in on the game: for lunch today in Manhattan, you can get a jambon-beurre from Jean-Georges Vongerichten at the Tin Building downtown, an Eric Ripert-branded version at L’Ami Pierre in Midtown, or Daniel Boulud’s at Epicerie Boulud on the Upper West Side. Chef Daniel adds gruyere to his sandwich, which seems a bit like gilding the fleur-de-lis. After all, you really only need three ingredients, because with butter, bread and pork you declaim these three words: 'liberty,' 'equality,' and 'fraternity.’

-

My wife lived in France twice, for a year each time, and still talks about the incredible baguettes and butter there many decades later (and as a Brit who used to pop over to Paris for a weekend -- thank you, Eurostar trains! -- I agree that French butter is a wonderful thing!).

Add a comment: