Notable Sandwiches #90: Indian Taco

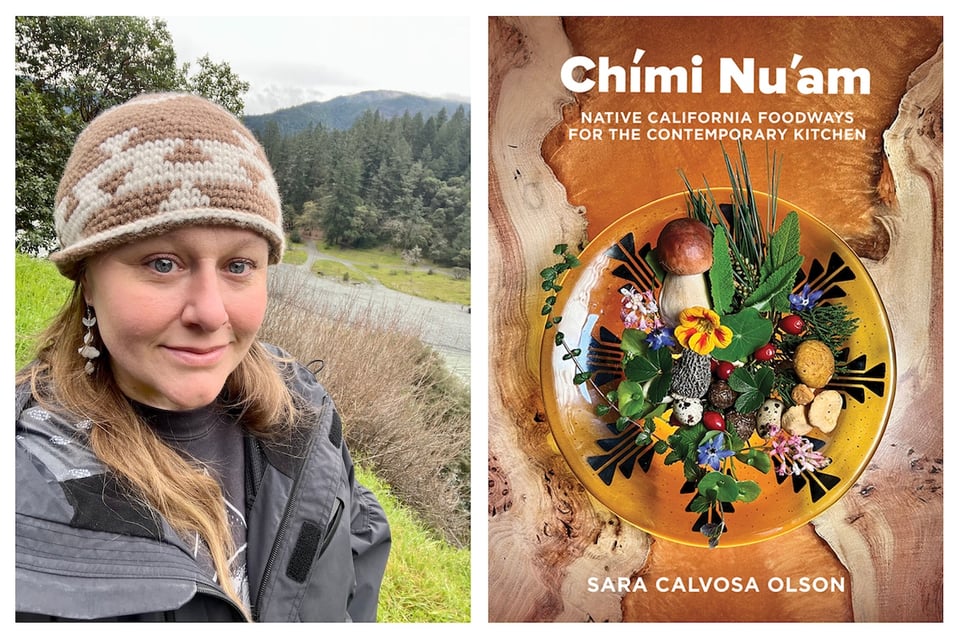

By Sara Calvosa Olson

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where I, alongside my charming and long-suffering editor David Swanson, trip merrily through the befuddling document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches. This week, food writer and friend of the Sword & Sandwich Sara Calvosa Olson returns with a guest column on a Native American favorite that goes by many names: NDN Taco, Frybread Taco, Navajo Taco, or Indian Taco.

BECOME A PAID SUBSCRIBER

I’m not sure how this cultural icon made it onto the exalted list of Wikipedia sandwiches but I am so happy to be guest writing this baddie for my pal Tal. Ayukîi nanífyiivshas, hello my friends! I’m pitching in this week because I guess you could say, I am somewhat of an NDN Taco devotee. A frybread aficionado. A dough nut.

If we’re just meeting, I’m Sara, a Karuk food writer from northern California. I also do community food sovereignty work, teaching with traditional foods like acorn, salmon, peppernuts, mushrooms, elk, camas bulbs, etc. My mother’s family is from the Ti-Bar area near the confluence of the Salmon River and Klamath Rivers. These historically abundant rivers are nestled into some of California’s most rugged, majestic mountains. My food influences on my Dad’s side are mostly Italian, and I have grown up seeing how complementary these two vibrant food cultures can be. And I have eaten probably 7000 NDN Tacos over 4 decades.

NDN Tacos (NDN is shorthand for Indian) are a Native struggle food, born of relocation and necessity. Their position is often controversial in our communities because they are emblematic of both our survival and our oppression. Every person in Indian Country has an opinion about whether or not frybread has any modern place on the Native food pyramid, but I think we can all agree that it has been deeply meaningful in our survival stories; many of us have frybread to thank for our continued existence.

Native ancestors survived violent removal tactics, oppression, occupation, starvation, environmental disasters, stolen children, backbreaking labor, and despair for murdered and missing relatives by mixing U.S. government issued commodities together and frying them in lard. The United States strategically forced Native people into dependency on these nutrient-deficient agriculture surpluses by disconnecting the people from their traditional lands and traditional foods. The United States would push all-purpose flour grown from wheat fields planted on our own stolen lands at the expense of ecosystems we’ve spent an incomprehensible amount of time caring for and nurturing into perfect abundance. A brutal tactic intended to continue the erasure of the Indigenous peoples. But Native ancestors all over this country said, “we’ll see about that,” and that’s why frybread will always slap. But it’s also unhealthy as hell, it’s fried dough and the witless United States managed to fail upward in the long game. But once we figure out diabetes, it’s all over for those absolute bitches.

The anatomy of an NDN taco is fairly simple. The fundamental cornerstone of every NDN taco is frybread. Every Auntie makes the best frybread. Every grandma, every Momma, they each have their own deeply held belief that in all the world, their frybread is the one true frybread. And in my experience, they are all correct. It’s truly a mystery. Personally, I like my frybread fluffy as heck, the color of sunny amber, with a texture like a luscious pillowy cloud. A real station wagon of fried dough. Recipes for frybread vary regionally and by household. I often like to add squash or nettle puree to my dough for a more vibrant flavor and to punch up the nutritional content of my frybread. Then I pat them out with my hands and fry them in sunflower or avocado oil.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription.

Once I’ve fried my dough to golden state perfection, I put a nice juicy scoop of spicy chili beans on top. My chili beans for this photo shoot were made with ground bison cooked with onions, garlic, California chiles, spices and Ramona Farms Tepary Beans. You want the consistency of your chili beans to flow just enough to flood all the hills and valleys of your frybread. Toppings include, but are not limited to, cheese, lettuce, salsa, crema, jalapeno, escabeche, lime, whatever feels like the biggest fuck you to the United States. You have to really make sure you put those good intentions into your food.

The more we reclaim our traditional foodways the healthier all of our communities will be in body, mind and spirit. There is hope for all of us in restoring these connections, so please consider seeking out Native organizations to support and join Indigenous people in their efforts to reclaim land. I know this subject is difficult to grapple with, but right now there is water flowing through parts of the Klamath River that hadn’t seen flows in a hundred years. Karuk kids will be kayaking down a river that their grandparents have never even seen in their lifetime. And I bet that every Native person who worked on the historic Klamath River Dam Removal Project is descended from a woman who garnered the strength to persevere, in spite of incomprehensible loss and grief, from a piece of frybread. What is your frybread, what is going to nourish you enough to keep fighting with us?

NDN Tacos

Serves 4 to 6

Recipe excerpt from Chími Nu’am: Native California Foodways For the Contemporary Kitchen (Heyday)

Squash Frybread

Ingredients

1 small red kuri squash

1-2 tbsps red chile powder

1-2 tbsp maple sugar or syrup

2.5 cups flour (plus more for dusting & shaping dough)

2 tsps baking powder

½ tsp salt

2 tsps yeast

½ cup milk

½ cup water

2 cups sunflower oil

Instructions

Preheat the oven to 350°F. Line a baking sheet with parchment paper.

Cut the squash in half and scoop out the seeds. Sprinkle the squash with chile powder and maple sugar and roast until tender, approximately 45 minutes. Remove the squash from the oven, put in a food processor, and puree it, skin and all.

In a large bowl, whisk together the flour, baking powder, salt, and yeast thoroughly.

In a glass measuring cup, briefly heat the water and milk together in the microwave until slightly warmer than room temperature.

Mix the water-milk and 1 cup squash puree together with the flour mixture. If too wet, add more flour ¼ cup at a time. If too dry, add more warm water 1 tablespoon at a time. Cover the bowl with a towel and set aside for 1 hour.

Elk Chili Beans

Ingredients

4 dried California or New Mexico red chiles

4 dried ancho chiles

2 quarts plus 1 cup beef or vegetable stock

2 whole canned chipotle chiles in adobo sauce (optional; leave out if you’re concerned about heat levels)

2 pounds of elk stew meat (or venison or beef or ground meat or whatever you have in the freezer), cut into 1-inch cubes

2 tablespoons sunflower oil

Salt and pepper to taste

1 tablespoon dried marjoram

1 teaspoon ground cumin

1 teaspoon dried oregano

3 allspice berries

1-inch piece of cinnamon stick

3 or 4 dried bay leaves

2 tablespoons tomato paste

2 tablespoons tomato powder (optional)

1 (15 ounce) can of diced fire-roasted tomatoes

3 whole cloves

1 white onion, peeled, top and bottom chopped off

1 whole garlic head, unpeeled, top and bottom chopped off

1 pound dried pinto beans, soaked in water overnight if possible

¼ cup masa

Instructions

This is a job for your slow cooker or pressure cooker. A slow cooker with a sauté function would be especially helpful to brown the meat first. If you brown the meat in a separate pan, make sure you scrape all the juices and bits from the bottom of the pan into the slow cooker too.

With a lightly damp paper towel, wipe down the dried chiles to make sure they’re not dirty or dusty (see Notes), then remove the stems and seeds. In a large cast-iron skillet, lightly toast the dried chiles over medium heat until fragrant, but keep an eye on them; if they burn, you’ll have to start over because your chili will be bitter.

In a medium saucepan, add the toasted chiles and just enough water to cover them by a ½ inch. Bring to a boil and then turn off the heat, letting them steep for 10 to 15 minutes. Drain the chile water into a bowl. (Taste the water. It can be bitter, but if it’s not, use it instead of the stock.) Put the chiles into a blender with 1 cup stock or chile water and puree. Add the chipotles in adobo sauce at this time as well if you like it hot.

Using the sauté function of your slow cooker (or over medium heat if you’re using a cast-iron skillet or pressure cooker), heat the oil and brown the meat well on all sides. Season with salt and pepper liberally. Add the marjoram, cumin, oregano, allspice berries, and cinnamon stick and coat the meat in the spices. Add the chile puree and stir, cooking the mixture for a couple of minutes.

Add the bay leaves, tomato paste, tomato powder (if using), and fire-roasted tomatoes and their juices. Cook for a few minutes until everything is simmering.

Poke the cloves into the top of the onion and add it to the pot along with the head of garlic.

Add the beans and 2 quarts stock and stir everything until it’s well integrated. Close the lid and slow cook on low for 4 to 6 hours, until the beans are cooked and the meat is tender.

Scoop out the bay leaves, cinnamon stick, onion, and garlic. Stir in the masa, close the lid, and cook for 20 to 30 more minutes, until thickened enough to stay on your frybread. Add salt to taste.

I like to serve this chili on top of Squash Frybread with baby kale or butter lettuce, chopped tomatoes, crumbled cotija cheese, a squirt of lime, crema, and some pickled jalapeños. The topping choices for this chili are endless and there is no wrong way to eat it.

-

When I lived in Tucson, a bunch of us from the office would ride our bikes to the Mission and the Tohono O'Odham nation members would be there making frybread, and we would buy some of the pillowy treats, slathered in local honey, and have a high-carb rush riding back. Thanks for this stroll down memory lane!

Add a comment: