Notable Sandwiches #89: Hot Dog

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where I, alongside my charming and long-suffering editor David Swanson, trip merrily through the befuddling document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches. This week, at long last: the hot dog.

Throughout this long and strange sandwich journey, now approaching the century mark, I have been fortunate enough to consider many things: sandwich provenance, the absurd number of ham sandwich varietals, colonialism, apartheid, culinary myth-making, and cuisine both regional and international. One thing I haven’t had to debate is whether any particular sandwich I’m writing about is a sandwich (let alone whether it is truly Notable), because I have completely abdicated this responsibility to the writers and editors of Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, the ever-mutating text we have embarked upon chronicling in alphabetical order.

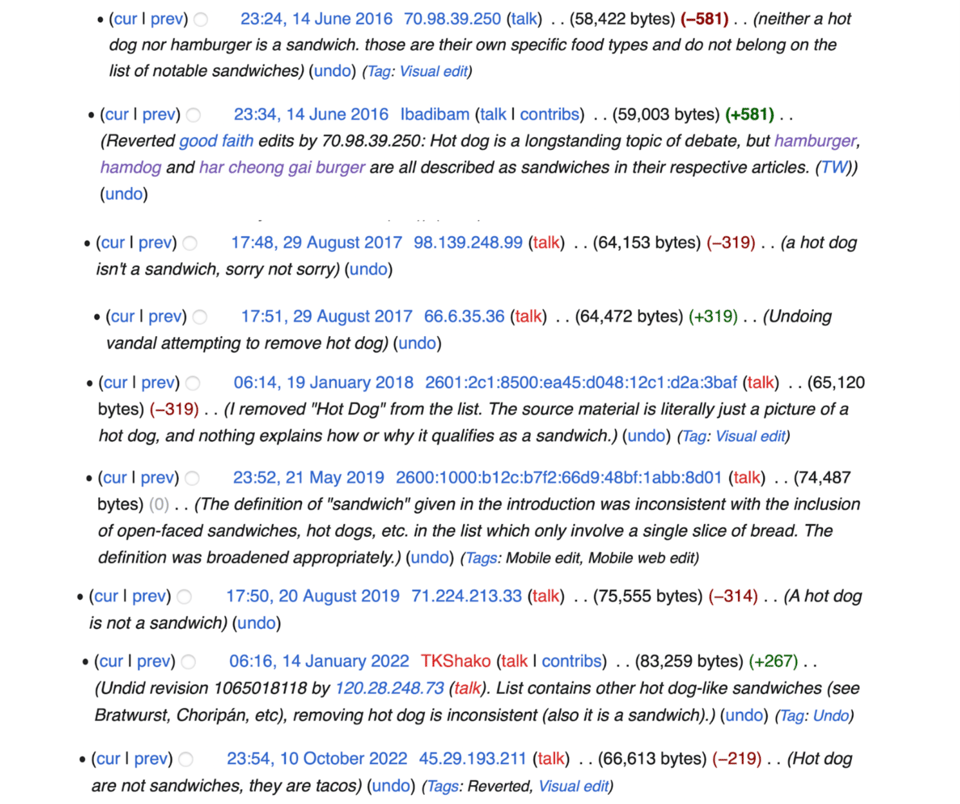

But what to do—as in the case of the hot dog—when even the Wikipedia editors seem to disagree?

If you look under the hood at the edit history, the “hot dog” page on wikipedia, and its entry on the List of Notable Sandwiches, is a riot of perpetual motion. The hot dog keeps being redefined, relitigated, removed and reinstated, like a king with periodic psychosis, or a Quiznos that may be a mob front.

What to do when one has ceded one’s authority to an entity that is, in and of itself, conflicted? Is a hot dog a sandwich? Who can say?

Of course, this is one of the defining debates in Internet history—it’s been addressed by everyone from Ruth Bader Ginsberg to John Hodgman, with associated verdicts by myriad major publications and many winking, smarmy Twitter-trend pieces besides. It’s been the subject of frenetic and often tedious contention for over a decade now.

But, dear readers, I wanted—no, needed—to seek out wisdom from higher authorities, rather than simply glean gristle and leftover bits of pre-prepared content and stuff them into the sausage casing of this column.

So I emailed thirty professors of semiotics, linguistics, ontology, psycholinguistics, information science and other pertinent disciplines, and encouraged these academics to get in touch. (One of the perks of being a journalist is the ability to email anyone I want, at any time, and ask them any question I feel like. Technically, anyone can do this, but being professionally nosy and having a direct reason to inquire—i.e., a newsletter that has to come out this week—lends a certain punchiness to the endeavor of query. This is what gives me the cojones to contact Yale professors to ask about sandwiches.) Lexicographers, literary theorists, and at least one gastroenterologist contributed their knowledge. I, a humble conduit without even a master's degree to my name, now convey to you the wisdom of the bold and the beautiful, the adjunct and tenured, the academics from all across this land and also Sweden, and Wales.

1. WHAT IS A HOT DOG?

Christopher Deutsch, Meat Historian, University of Missouri:

Let’s start by defining hot dogs by using history. The exact date when “hot dog” emerges as a term is unknown, but possibly the 1890s via baseball game vendors. It was at ballgames and at Coney Island that hot dogs became popular. It was the perfect snack food for eating on the go at these destination attractions. Circa 1900, there was even sheet music for a song called “The Hot Dog Man” as the idea of the hot dog was cemented in American culture. Notably, the cover showed the titular man placing a warm hot dog into a hot-dog-shaped bun.

What made hot dogs catch on can also help elucidate an answer. Hot dogs are a type of sausage inspired by the way sausages were prepared in Frankfurt [frankfurter] and Vienna [wiener]. They are soft, pre-cooked, fresh sausages that are made from lightly seasoned meat and lots of fat, perfect for being heated by water and for selling them on the go. They are also perfect for a bun, which were sold along with all kinds of sausages as early as the 1870s to working men and in pubs/beer gardens. The hot dog proved the most popular style for easy eating thanks to the ease of heating and the soft, palatable meat.

Hot dogs are also a distinctly American food item, born out of the immigration waves of the nineteenth century combined with the growth of urban environments and industrialization. That gives hot dogs an identity that, I think, is at odds with how we think of sandwiches, which are a generic type of food. Sandwiches contain multitudes. There are the Delmonico’s type of fancy and extravagant versions, there are the subway/hoagie types, types you dip, or how about a bánh mì, not to forget the trusty peanut butter sandwich. I think that the identity of the hot dog and the branded nature of the product makes them not feel like a good fit for the generic term “sandwich” the way an Italian 6” with bologna (another softer sausage) does. All of this is to say that the history of the hot dog makes them difficult to place since they are at once a snack and a meal.

2. THE BUN MAKES THE SANDWICH. YOU YOURSELF MAY BE A SANDWICH. ALSO, YOU’RE SAYING HOT DOG WRONG.

Sarah Stroup, Philologist and Professor of Classics, University of Washington:

Sometimes a hotdog is just a hotdog (by the way, this must be written as one word, as it is a compound noun; "hot dog" describes a dog… that is hot).

A hotdog is not a sandwich; it is the meat. Ditto a hamburger: a hamburger is not a sandwich; it is the meat. You can have a hotdog without the bread; it is still a hotdog. In Hawai'i, where I was born and raised, there is a thing called "loco moco," which is—improbably—rice topped with a hamburger topped with a fried egg, topped with gravy. The hamburger is the meat.

A BLT is definitively a sandwich, because if you just have bacon, lettuce, and tomato, that's just a bunch of stuff on your plate. A Reuben is definitively a sandwich—without the bread, it is just meat. But falafel… is falafel. You might have falafel in a pita, sure. But the fact that this is then sometimes called a "falafel sandwich" makes it clear that the falafel itself is the protein, and it is not a sandwich until it meets the pita. And this is key.

If a hotdog is a sandwich, then three (Ok, whom do I kid; I usually eat five or six) balls of falafel are a sandwich (and they are not). If a hotdog is a sandwich, then tuna salad is a sandwich, and we know that it is not, because we always say "tuna salad sandwich." I mean, not always. Only sometimes.

A hotdog in a bun might qualify as a sandwich (in the ridiculous way that now maki sushi and taco salad bowl might do the same when all good people know that this is a lie), but I now propose that for something to be a sandwich, it is the starch (bread whether leavened or not, corn flour, even rice) that makes it so.

Last night I was thinking that a definition of "sandwich" might be: some sort of protein wrapped in some sort of carbs, which would make you, dear reader, a sandwich—and I am a sandwich, as well.

3. LET’S GET INTO THE ONTOLOGY OF THE HOT DOG. ALSO, WHO IS “WE” WHEN WE ASK THIS QUESTION?

Ásta, Professor of Philosophy, Duke University:

So, the sandwich. And the hot dog.

I think of food items of this sort as similar to artifacts. Just as what makes something a chair is not its material, color, or shape, but its function, so a type of food serves a function. And the function isn’t just its nutritional value, but involves conditions under which the food can be used, consumed, or even put on display. Handheld food items can be offered at cocktail parties, street corners, and the beach. Non-messy handhelds can be consumed in white dresses and on black couches; handhelds that don’t need refrigeration can sit in a saddlebag or trunk for days.

When we ask what makes something a sandwich we should also ask why we need to know, and who we are. The "we" is a culturally specific we. The type of handheld that is a sandwich has a lineage and it is a cultural one. That cultural lineage informs the conditions under which it can be used, so in that way informs its function. Then the question is why we are asking the question. Why do we want to know? What hinges on the answer? That is going to guide us in making our question more precise. What is our purpose?

If we are inviting people to English Tea, the hotdog is not a sandwich.

If we are feeding people who eat pork and gluten some bread and meat as opposed to ramen, the hotdog may be our favorite sandwich.

But I suppose that most of the time when we ask the question, we are already making some assumptions regarding its use which block out the hotdog as a sandwich and that in those scenarios the hot dog and the sandwich are both a type of handheld.

4. LINGUISTS WEIGH IN.

Elizabeth Coppock, Assistant Professor of Linguistics, Boston University:

This is not a matter that an “expert” can settle, at least not without any data collection. I would need to survey native speakers of English across a range of geographical regions, taking other social factors into consideration. I would need to design the survey carefully, and consider a range of possible contexts and conversational goals. Just because I have studied linguistics doesn’t mean I have any evidence that I can use to weigh in on this matter.

Myrdene Anderson, Professor of Linguistics, Purdue University:

It is perhaps worth discussing if (especially) native speakers/signers/writers wish to. However, even were languages and languaging not continuously changing, and being modified, there are no definitive rules. Patterns, not rules, emerge via habit and temporal consensus. There are no experts in languaging other than the speakers/signers/writers themselves.

Laurel Brehm, Assistant Professor of Psycholinguistics, University of California Santa Barbara:

My hot take:

Categories are best viewed as something with probabilistic separation: clear category boundaries cannot be drawn on one sole feature of an item (like whether there are two pieces of bread), but on a combination of all relevant categories features.

What counts as a member of a category depends somewhat on the usage in question because of which features are highlighted.

This roughly follows a so called ‘exemplar’ or ‘prototype’ model.

So, hot dogs are sort of sandwiches. They’re not a good exemplar of the sandwich category, but they’re not clearly outside of the category either.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription.

Matt Garley, Assistant Professor of Sociolinguistics, York College:

Linguists try not to be the arbiters of this sort of debate. As a field, we tend toward a descriptive approach (i.e., asking ‘how do people use language?’) rather than a prescriptive one (i.e., ‘this is how language should be used’).

Many of the discussions I’ve seen online about this debate focus on the denotative meaning of the word ‘sandwich’, separated from context and associative meanings. The argument generally invokes formal logic, and from a linguistic standpoint, this would fall under the study of lexical semantics. Take Merriam-Webster’s definition for sandwich: “two or more slices of bread or a split roll having a filling in between.” If a hot dog is a type of “split roll having a filling in between”, then it obviously meets the criteria set forth in that definition, and a hot dog is therefore unproblematically a sandwich—we could say ‘sandwich’ is a hypernym of ‘hot dog’, and ‘hot dog’ a hyponym of ‘sandwich’. However, this all relies on a dictionary definition, which is only an approximation of the conventional meaning, the meaning most speakers agree on most of the time.

From a descriptive perspective, we want to know: How do people use language in this case? Do people commonly or regularly refer to a hot dog (outside of this particular debate) as a sandwich?

For more insight, let’s turn to pragmatics, a subfield of linguistics that examines how context can account for meaning. If a friend said “Hey, can you grab me a sandwich from the corner store?” and I said “What kind?” and my friend replied “A hot dog!” I’d probably find the conversation a bit strange, or just assume my friend changed their lunch order. A pragmatic explanation for this sort of interaction can be found in H.P. Grice’s cooperative principle, which suggests that in straightforward cases, conversations proceed under several assumptions, or maxims, shared by the speaker and hearer.

All of this is to say that I’m inclined to suggest that in my experience (and perhaps systematic research is needed) speakers of what is called General American English, at least, do not conventionally treat hot dogs as sandwiches. The caveat, here, is that language is always changing, and semantic shifts are possible. The word ‘tea’ once referred exclusively to the tea plant, camellia sinensis (black, green, white, and oolong teas are all this type), but in modern usage, ‘tea’ is widely used in ways that encompass a range of herbal infusions made from different plants, like rooibos, chamomile, etc. So, it’s entirely possible that, in our cyberpunk future, we’ll start considering hot dogs just another kind of sandwich—but I’m personally rooting for the semantic broadening of ‘glizzy’ to eventually refer to all foodstuffs.

Sarah MacDougall, Masters Student in Linguistics, University at Buffalo:

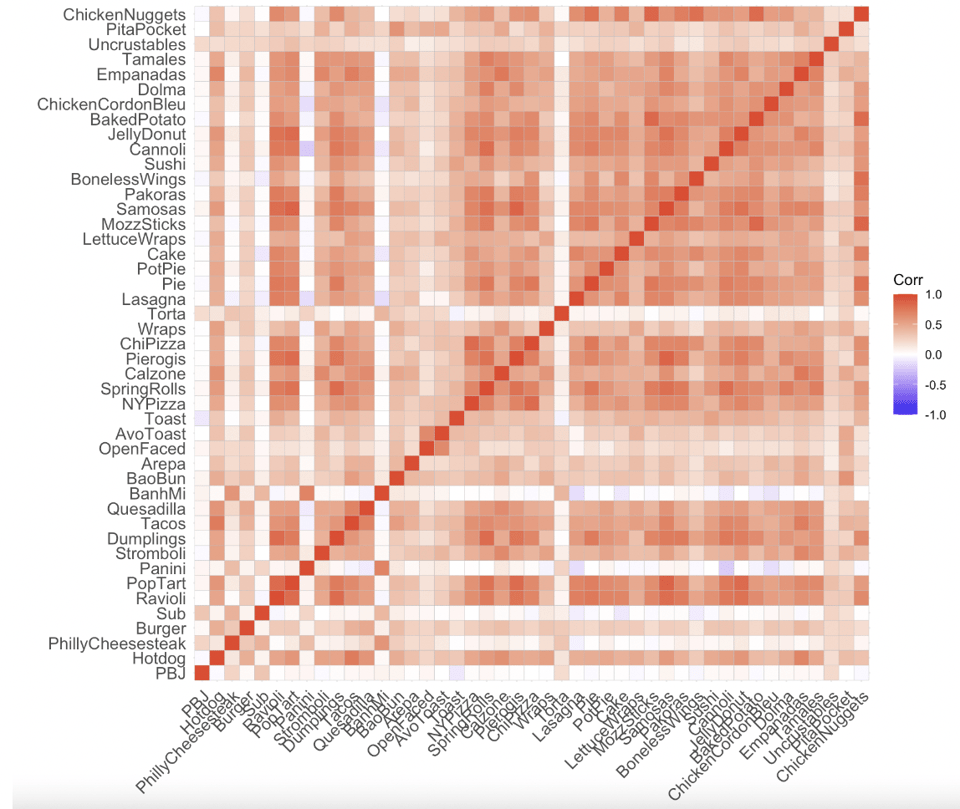

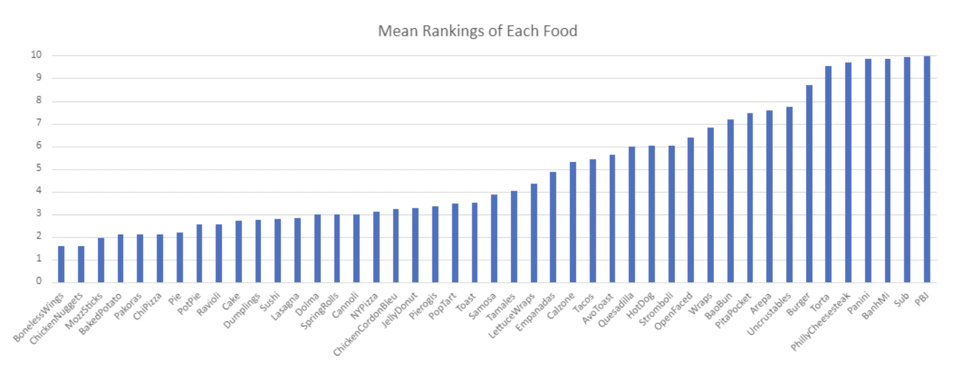

I'm a master's student in linguistics, and for a semantics class last semester, I decided to take a crack at a quantitative analysis of the sandwich space by surveying people and having them rank the "sandwichiness" of 45 different food items. I ended up with 112 people. I also asked for qualitative opinions at the end, and people ranged from strong opinions about what a sandwich is, to saying that with a liberal definition, all of the foods I provided could be considered sandwiches. Hot dogs and tacos are right next to each other, so they are siblings.

5. HOT DOGS ARE A DIGESTIVE HAZARD, BY THE WAY.

David Westrich, MD, Professor of Gastroenterology, The Ohio State University:

A hotdog is a sandwich. I’ve certainly pulled a lot of them out of the esophagus, that’s for sure. A common GI emergency is a food bolus, where the food gets stuck in the esophagus. If it sits there and doesn’t get removed, over the course of days it will cause irritation and inflammation eventually leading to an ulcer, which can perforate to form a hole, infection, ultimately death if not otherwise removed.

Usually the problem is from a narrowing in the esophagus causing a holdup. Liquids and soft foods may pass through without issue, but the foods most likely to get stuck are dry breads and meats. They don't compress well and can't get past the narrow area. Bread will eventually dissolve with time due to the starch-digesting enzyme amylase in the saliva, but meat only breaks down in the stomach.

One of the worst cases I've seen was a prisoner who presented 3 days after trying to swallow a whole sausage. So while a hotdog may be a sandwich, to me professionally, it’s a liability.

6. DON’T BELIEVE EVERYTHING YOU READ IN THE DICTIONARY.

Jesse Sheidlower, Lexicographer, Columbia University; Former Editor-at-Large, The Oxford English Dictionary:

Is a hotdog a sandwich? Yes! And no! Unfortunately that's the way it is.

When you're looking at broad classes of nouns like this, you're focused on what you'd call "typicity". For example, soup could be defined as 'liquid food'; this definition would include 100% of things that might even possibly be called "soup", but it would also include a lot of not-really-soup-y things—like cereal or martinis. Soup is typically based on stock, and served hot, and is eaten with a spoon, and is served at the start of a meal, and is savory, and (in America, but not Britain) contains solid bits, and so on. But there are many things that are usually considered "soup" that violate these patterns. Vichyssoise is served cold; there are fruit soups that are cold, non-savory, and served at the end of a meal; etc. And then there are things that violate these patterns that are very much not considered soups. The archetype of this is cold cereal, which is mostly liquid, savory, with stuff in it, and eaten with a spoon, but which is not soup. Dictionary makers tie themselves into knots to try to get the different permutations of sandwiches right.

The general thing to know about dictionaries is that you're usually not trying to capture the complete and exact description of something; you're trying to get a general picture of what something means. This is hard enough for concrete nouns that we more or less know, like "horse" or "sandwich"; it's impossible with abstract nouns like "freedom" or "beauty". One of the most famous definitions in lexicography is the one for "door" in Webster's Third of 1961:

"a movable piece of firm material or a structure supported usually along one side and swinging on pivots or hinges, sliding along a groove, rolling up and down, revolving as one of four leaves, or folding like an accordion by means of which an opening may be closed or kept open for passage into or out of a building, room, or other covered enclosure or a car, airplane, elevator, or other vehicle."

This is what happens when you try to be exact—you get something useless.

So most dictionaries, that are written for native speakers and that assume a good-faith effort to understand the definition, give a reasonably broad definition, that will include most things that should be included and exclude most things that should be excluded.

There are, conventionally, two main types of lexicographers: lumpers and splitters. Lumpers include as much as possible ('liquid food' for soup); splitters write a dozen super-narrow definitions, and when a new variant comes up, they write another one.

Dictionaries are generally more lumpy than splitty. A sandwich is a food with something inside a bready thing. Trying to be super-precise is only going to lead to frustration (or the "door" definition above): Most people feel that a meatball sub is a kind of a sandwich but a hot dog isn't, but that's very hard to explain, so unless you have a definition like "… or a split roll having a cold or hot filling (that is not a solid length of sausage)…", you're kind of stuck.

If I can turn serious for a moment—and this is very serious—the reason that this is genuinely important, and not just a parlor game, is that people sometimes put a lot of faith in dictionary definitions. In particular, courts use old dictionaries to try to determine what words meant at a time when laws were written. But that is very much not how dictionaries should be used. If it's this hard to determine what a "sandwich" is, what are we supposed to do about words like genocide, or to bear arms? Or woman in reference to a trans woman? People literally die because dictionaries are misused. There are ways to attempt to answer these questions—corpus linguistics, sociolinguistic interviews—but thinking that a dictionary is an exact map of reality is not a correct one of these.

7. WHAT WOULD ROLAND BARTHES THINK ABOUT THIS QUESTION?

Neil Badmington, Professor of English Literature, Cardiff University; Founder of the Journal of Barthes Studies:

Roland Barthes knew that what we eat is more than merely biological sustenance for our bodies. An edible object can be something that, in Barthes’s words, “society has endowed with a signifying power”. Food, in short, has meanings—it signifies as it satiates. We stuff our mouths in order to satisfy a basic biological need, yes, but at the same time we are consuming the values that culture has baked into what fills our stomachs.

In Mythologies (1957) Barthes serves up a delicious and memorable example. To devour a rare steak, he proposes, is to subscribe to a “sanguine mythology” that promises the diner “a bull-like strength”. Steak also has “a supplementary virtue of elegance” that, for Barthes, manages to unite “succulence and simplicity”. Les frites, meanwhile, are a “nostalgic and patriotic” presence upon the plate alongside the steak; they are “the alimentary sign of Frenchness”, says Barthes, and to feast upon them is to pledge allegiance to the nation. Semiology recognises that these values are not natural, not an inherent ingredient of the food; instead, they are culturally produced and reproduced at the dining table from day to day.

Classification is about order and boundaries. Or rather, it’s about trying to create such things. If the classification of food is cultural, not guaranteed by nature, it follows that categories are open to question and to being dished up differently. The tomato, for instance, is technically a type of fruit but, in my culture at least, it’s treated as a vegetable. Unlike the apple, as Seinfeld’s George Constanza once observed ruefully, the tomato “never really took off as a hand fruit”. Taxonomies can be taxed, turned.

And then there’s the hot dog. How might we classify it? Is it a sandwich or not? In one respect it seems to fit the bill: it consists of a filling between bread and is usually eaten with the hands. But a hot dog is unlikely to be found on the menu in a sandwich shop and often has its own special outlets, such as the street carts of New York. The hot dog poses a challenge for traditional taxonomy: it is both a sandwich and not a sandwich; it fits and doesn’t fit. The category, in short, doesn’t quite cut the mustard. Perhaps we need to wean ourselves off taxonomy or, if we need help, find someone to wean us: a weaner. What the bun-wrapped wiener demands instead is tautology—that “verbal device which consists in defining like by like”, as Barthes puts it. The answer to Talia Lavin’s question would then become, quite simply: the hot dog is the hot dog.

8. WHAT ABOUT WITTGENSTEIN?

Paul Vankoughnett, Mathematician and Visiting Professor at Texas A&M University, and also one of my best friends and favorite people:

Wittgenstein famously pointed out that we can often recognize members of a family as related to each other, even though there’s no single feature they all have in common; other notoriously difficult categories like “game” could be similarly identified by a network of resemblances rather than a set of necessary and sufficient conditions. Everyone who hears this recognizes it as true and even obvious; what’s interesting is that the urge to define and delineate doesn’t go away. Part of me thinks that it echoes a deeper urge to make sense of our shared world. Another part of me thinks that we just learned how to think this way in school.

All that said, if you’ll take an argument from origins, the Earl of Sandwich wanted to be able to hold his lunch in one hand while he gambled. Is there any modern food item more of the spirit than the hot dog? If I can turn your non-sandwich into a sandwich by running my pointy little fingernail down the length of your bun… your definition ain’t shit.

9. THE SEMIOTICS OF THE HOT DOG.

Frankie Huang, Consulting Semiotician:

If you've been to Taiwan, Thailand, or other countries with a thriving night market scene, I think hotdogs would fit right in at a street food cart alongside blood rice cakes, sweet grass jelly, and bubble tea. I think hotdog's simplicity, quickness in being ready-to-eat, and smallness makes it an ideal street food, which is a very loose category defined less by form and more by occasion.

So I think my verdict is that it's a street food, if I must put it in a bucket.

J.D. Connor, Associate Professor, Media Studies, School of Cinematic Arts, University of Southern California:

A sandwich is not a thing; it is a set of practices. Attempts to settle what is or is not a sandwich founder on the rocks of ontology. We ask what things we do with & around sandwiches. Some of those practices are likely defining, others disqualifying. For us. For now.

Our sandwich practices are robust but always incomplete. Our language races to catch up.

One practice that is defining is jamming it in your face. One practice that is disqualifying is tipping your head.

Tacos are not sandwiches.

Holding a sandwich by its top and bottom is defining. Holding it by its sides is disqualifying.

A hotdog has no top; its bottom is a bare connection. We hold it by its sides.

A hotdog is not a sandwich.

The topology of baked goods will not save your ontology.

No one doubts that a sub roll, incompletely split, is not in danger of losing its sandwichness. The laid-open roll is but an arena of action for the sandwich artist or a facilitation of toasting.

But, you will say, “we call an open-faced sandwich a sandwich.” That is right. Our language is full of such traps. Our practice is not. Make me half an open-faced turkey sandwich.

A sandwich is not a thing; it is a set of practices.

10. CAN WE BE RESCUED BY LIBRARY SCIENCE?

Julia Bullard, Assistant Professor, School of Information, University of British Columbia:

I teach in the Masters of Library and Information Studies program where I'm mainly responsible for introductory and elective courses on how to organize stuff to make it findable. In the required, first-term course on information organization, I teach category theory and the limitations of the classical theory of categories (Aristotle's version where categories have strict rules for membership and criteria determine what's in or out) by having them attempt to create a coherent definition for "sandwiches" that is consistent with the objects they believe to be sandwich and not-sandwich. While I do have a coherent definition that leaves out hot dogs, the exercise is so close to impossible as to teach the students that categories are socially constructed and even those we think are stable and meaningful can't stand up to the requirements of the classical theory.

Here's how you define sandwiches to leave out hot dogs:

a meal consisting of layered foods

all layers edible prior to assembly

served and eaten horizontally

11. WOULD A HOT DOG BE A SANDWICH IN ANCIENT GREECE?

Jim Lohmar, Senior Lecturer of Classical Languages, College of Charleston:

I am the senior lecturer of classical languages at the College of Charleston. A hotdog is a sandwich.

Importantly, the Earl of Sandwich did not invent the sandwich. The Earl’s personal chef invented the sandwich. I study the ancient Greeks and Romans, who famously didn’t often eat with utensils. A hotdog at base comprises bread (Latin “panis”) and meat or meat substitute. It’s eaten with the hands. Basic geometry, architecture, mode of consumption and human physiognomy point toward hotdog = sandwich.

Matt Solomone, Professor of Mathematics, Bridgewater State University:

People often call math a "universal language", and many who are drawn to studying math will tell you they're attracted by the promise of "universal truths". I see these sentiments as expressions of a need for both univocality and certainty, a desire to divide the true from the false in ways that are self-evident to anyone who has sufficiently studied the subject. A cynic might say this is also the desire to divide the Right from the Wrong, for the purposes of wielding the former against the latter…

[According to] Aristotle math must be true because we can see its truths reflected in our physical world. We can recognize, for example, that six eggs can be arranged into a rectangular grid but seven cannot—highlighting a fundamental difference between a composite and a prime number. In this view, even if mathematical truth might be supernatural, it is beholden to the natural world to lend it credence: its truths are "about" something observable, measurable… Euclid discovered four axioms from which much of geometry can be proven (though he also had a troublesome fifth, the non-necessity of which ended up birthing a whole constellation of new types of geometry later on, to which we owe the theory of general relativity among others!). This program is sometimes called the "formalist" agenda, and holds that almost all mathematical truth is contingent on prior truths, until we arrive at its axiomatic firmament.

Which brings us to sandwiches. I find that most people's tacit ontology of mathematics is both quite Platonic (math is supernaturally true and beyond human agency to affect), and also quite static (it's been true since the beginning of time). In part that's because traditional math education is too often both ahistorical and authoritarian: it positions mathematical truth as outside of both time and culture, and positions the teacher as the lone source of authority over what is judged correct. I want neither of these to characterize our teaching. For one thing, these give a sterile and fundamentally inauthentic impression of how "real" mathematics happens; and for another, these reify a culture of exclusion in which one only belongs to the extent that they have Right answers (and those answers are necessarily the same).

But that is the beginning of the story and not the end. Even fundamental definitions in math (such as "what is a prime number") have undergone changes over time when the community found the existing version to be insufficient. It is all up for grabs, and we can all be up for grabbing it.

12. WHY DO WE ASK THIS QUESTION?

Mark Crimmins, Associate Professor of Philosophy, Stanford University:

Any well-defended answer to that would take many pages and encompass so many (great, interesting) issues about language. Still, I'd like to offer something to your reader. If you think what counts as a "sandwich" is unclear or somewhat arbitrary, then you had better examine in that light whatever principles you take to be important about sandwiches. Similarly for "baby," "woman," "conscious," "intelligent." Are you sure that the (perhaps unclear) applicability of these ordinary-language terms marks what is crucial to the distinctions carved by your prized principles?

13. WHAT WOULD YOU GIVE TO BE RIGHT? ARE WE ABLE TO ASK QUESTIONS WITHOUT CHANGING OURSELVES IN THE PURSUIT OF THE ANSWER?

Alana Vincent, Associate Professor, Religious Studies, Umeå University, Sweden:

Here’s what I really think, as a scholar of religion: the answer to “Is a hot dog an sandwich” is far less interesting than the mental and emotional energy people put into defending the norms that shape their worldview, which are destabilised when the question is raised. “Is X a Y”, for any value of X or Y, implies that the answer COULD be yes (or no), and creates a consciousness of similarity (or difference) where none existed previously. By bringing categories into question, it shows that they can be questioned; the actual answer is of very little significance in the face of this terrifying revelation.

Beginning in the late 18th century, “Is X a Y” was asked about entire categories of human beings who had previously been excluded from the category of rational political actors (Jews, women, people of color, etc.), and the world we now live in was shaped by the destabilisation that question produced in the minds of the people who asked it; in many ways we are still suffering from the after effects. For the cause of universal human equality this is a small price to pay, of course, but would you really want to take that risk for a hot dog?

At the end of the day, academics are just like all of us, but better at answering questions with more questions. I found this journey into sociolinguistics, metaphysics, category theory, religion, gastroenterology, classics, semiotics, psycholinguistics, and ontology enlightening, although not necessarily definitive on the question of whether a hot dog is a sandwich. And as I am the only member of my family without an advanced degree of any kind, I’m glad the experts agree:

Quod erat demonstrandum: the question is unanswerable, and suspect in se.

Per aspera ad astra,

Talia

-

That was a wonderful romp through a "baker's dozen" different opinions and it greatly brightened up my Friday morning! Thank you.

-

Brilliant, utterly brilliant.

-

This is all amazing. But I think its missing discussion that the deciding factor of a sandwich is not the filling - in this case hotdog - but the nature of the casing. Merriam-Webster’s definition for sandwich: “two or more slices of bread or a split roll having a filling in between.” is soooooooo wrong because a roll is a roll; a filled roll; a roll and sausage (not a sausage roll - that's a totally different beast that involves pastry). The filling needs to be encased in a bread type covers that need to have been cut from a larger whole ie a loaf of bread, a large ciabatta or foccaccia. It's the fact that there is bread left over - potentially to make ANOTHER sandwich - is what makes it a sandwich. Thus a sub is not a sandwich.

-

I love how many of the answers are clearly right but contradict each other. This could maybe have been explained by consulting an anthropologist of the kind who understands that sandwiches are socially constructed--it's a sandwich if the community accepts it as a sandwich, and there are many communities, but also some of us belong to several of those. One person had a very good analytic-philosophy kind of answer--that if you asked somebody what kind of sandwich they'd like you to get them from the deli you wouldn't expect them to answer "hotdog". But the same argument would apply to a banh mi or a croque-monsieur, because the deli doesn't carry those either, but nobody would deny that these are sandwiches, though they might say "they're not my sandwiches."

I think the corner store argument still applies even if the store does carry hotdogs, like a 711 or a Costco. In any case, I think the point is not just that it’s unexpected if someone asks you to pick up a hotdog after saying they are in the mood for a sandwich, which could indeed be explained by hotdogs not being carried at the store. Rather, it sounds like they changed their mind about what they want. Here, whether or not the particular store happens to carry the item doesn’t seem as relevant.

This being said, I agree with your point that this argument is relative to a community of speakers, and it’s possible that there could be different communities using “sandwich” differently. Is just that, if this sort of argument applies to all users of the words “hotdog” and “sandwich”, it would be pretty good evidence that hotdogs are not sandwiches, whether these concepts are socially constructed in any special sense or not. They seem no more socially constructed than many other concepts for which we can definitively answer “Is X a Y?” questions.

Add a comment: