Notable Sandwiches #85: Hani

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where I, alongside my editor David Swanson, trip merrily through the baffling and mercurial document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week, a Detroit specialty: the Hani.

I was born in 1989, into a world of such awesome prosperity and tranquility that I took it for granted until much later. Only now that things have boiled into such an toxic lather do I look back on those years with wonder. Some of this is, no doubt, because it was my childhood, and I had a good prosperous childhood in a good prosperous home. But I think overall, in this country, it was a fat and lulling time, a time when technological advancement seemed wondrous, betterment inevitable, peace within grasp. It was also well into the era of convenience food: asparagus from Mexico, avocados from California, strawberries in winter, and McDonald's from coast to coast.

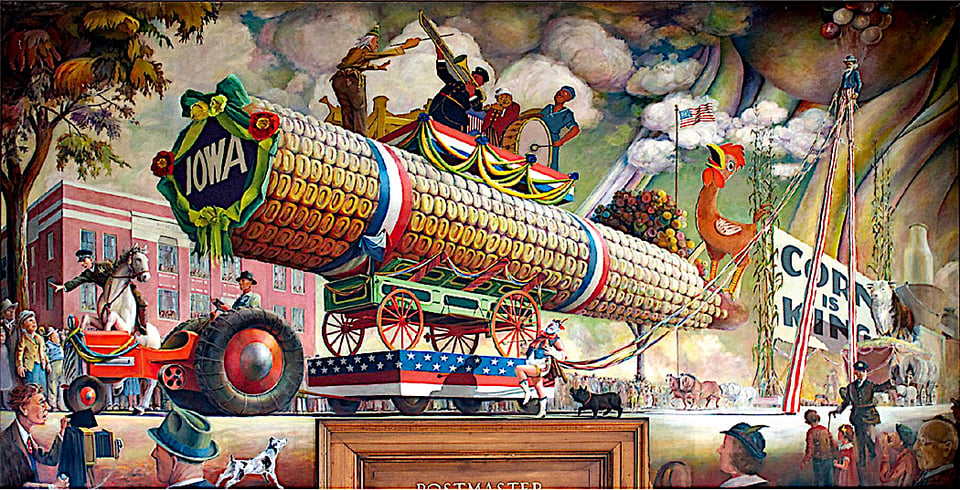

It wasn’t always this way—of course. One of the better books I’ve ever stumbled upon is a remarkable anthology, edited by the redoubtable Mark Kurlansky, called The Food of a Younger Land, a series of essays from an ultimately scrapped Works Progress Administration project called America Eats. Part of FDR’s Federal Writers Project, which sought and found employment for writers during the Depression (for the record, I would like the Federal Writer’s Project to return please), America Eats was going to be a portrait of a national cuisine that was profoundly stratified by region.

America is and has been a huge patchwork quilt of different landscapes and different cultures, thinly and nominally held together by a federal government and a civic religion of flag and anthem and Constitution. But the America of the late ‘30s and early ‘40s was far more so, without any of the national franchises or strip malls that lend contemporary American towns their monotony, the feeling that one is always roughly in the same suburb. So The Food of a Younger Land, despite being written in a time of desperate hunger, is also a chronicle of a staggering variety of cuisine: Vermont pandowdy, New York luncheonette jargon, Mississippi persimmons, Georgia possum and taters, “Pop-Corn Days” in Nebraska and wild-duck salmi in Utah, clambakes in the Northeast, fresh salmon grilled in Oregon. It’s a mouthwatering, staggering kind of book, telling the story of a country pieced together from fifty smaller countries, each with their own rivers and their own recipes.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription.

Which brings me back to the present day, and the subject of this sandwich column, which is a regional specialty from Detroit: the Hani, or—as it’s known more generically, subject to culinary copyright—the chicken finger pita wrap. It’s not squirrel stew or seaside clambakes, but I tend to take regional claims to cuisine seriously, and the Hani is a queer fish in that sea. It was spawned by a line cook named Hani in 1985, in a restaurant owned by Greek immigrants, named after New York’s Coney Island. (The Coney Island Dog, a hot dog with chili sauce, mustard and onions, is another Detroit specialty, though I’ve never seen one at the actual Coney Island in Brooklyn, a beautiful ramshackle place of terrifying wooden roller coasters, an attraction called the “Freak Show," seedy Russian baths, Nathan’s Famous, a really good aquarium, funnel cake and endless freezing ocean. I love Coney Island with my whole soul. You can stock up on Russian groceries on your trip—pelmeni and caviar abound in next-door Brighton Beach. I digress, I digress…).

Detroiters—or at least Detroiters paid to write about food—are really enthused about the Hani. I mean, it’s a good concept: fried chicken wrapped in pita, with lettuce and tomato and a side of ranch. I would absolutely eat the Hani with no regrets, although I would probably eat it with a side of Tums. It sounds delicious and deserves to have survived, thrived and disseminated across Detroit, whether known by its Madonna-like mononymous sobriquet or its descriptor. There’s also something pleasing about the words “chicken finger pita wrap.” It rolls off the tongue nicely, a pleasant little tetrameter.

Still, it lacks a bit of the je ne sais quoi of the older stories of regional cuisine. Here’s a little sample from Detroit-born Nelson Algren’s WPA-funded tale of Michigander food in the ‘40s, in a subsection about Michigan entitled “Land of Mighty Breakfasts”:

"Paul Bunyan felt there were two kinds of Michigan lumber camp cooks, the Baking Powder Buns and the Sour-Dough Stiffs. One Sour-Dough Sam belonged to the latter school. He made everything but coffee out of sour-dough. He had only one arm and one leg, the other members having been lost when his sour-dough barrel blew up."

(There were apparently a lot of lumber camps in Michigan back then. Also, I once read an entire book about baking powder, and can tell you it was a relatively new invention back then, having been industrially produced for less than half a century, as opposed to sourdough, which dates back to the happy time humanity introduced moistened wheat to free-floating, beneficial lactobacillaceae).

Or, Algren continues:

“Michigan house-raisings were conducted to the accompaniment of a great deal of liquor and in some quarters it was not considered proper to have a raising without it."

“Much of rural family life was conducted in the country kitchens... From the cellar would come squash, rutabagas, cabbage and some canned fruit and pickles. There was fresh corn meal so recent from the mill that it had not yet become infested with weasels."

Nostalgia for privation is silly. So is nostalgia for simpler times, and for childhood, although silly in a different way (times were simpler because you were a child, usually; privation is privation, and weasel-infested cornmeal sounds awful). Still, there’s a lot of unwonted homogeneity about, a lot of enshittification enabled by the sameness of everything, squeezing the life out of things as it flattens them. I remember meeting a girl from Montana when I was younger; her drive through New Jersey had astounded her, she said, because she had never seen “so little nothing.” I remember also a time working as a ranch hand one summer in northern Oregon, and finally understanding what she meant: the vast gaps between little settlements, the big, big sky, the huge land rolling under the car, the fantastic tortillas from the little food trucks set up for the orchard hands, and the whole horizon rolling out like God’s best blue satin tablecloth.

It’s good when places are different, in identifiable ways, stamped with their own uniqueness, and proud of it. Despair and privation and salvage and scramble aren’t good, asparagus in winter is a lovely thing, but there’s something bled out of the water of a place when you can travel up a coastline and eat the same meal, more or less, in every town. So I salute Detroit and its Hani, a little pita-wrapped flag of uniqueness in a time when all of us are being scrunched so hard into sameness. I pray it will be forever free of weasel infestation, and I wish you the same. And do pick up The Food of a Younger Land. It’s delightful.

With love,

Talia

-

Thank you for your generous spirit, Talia. I could read your writing all day, about anything. Unfortunately your serious work on right-wing threats is too heavy for my poor challenged mental health to engage with directly. I do pay attention, however, and am frightened enough to do what I can to stop it.

Add a comment: