Notable Sandwiches #81: Ham Redux

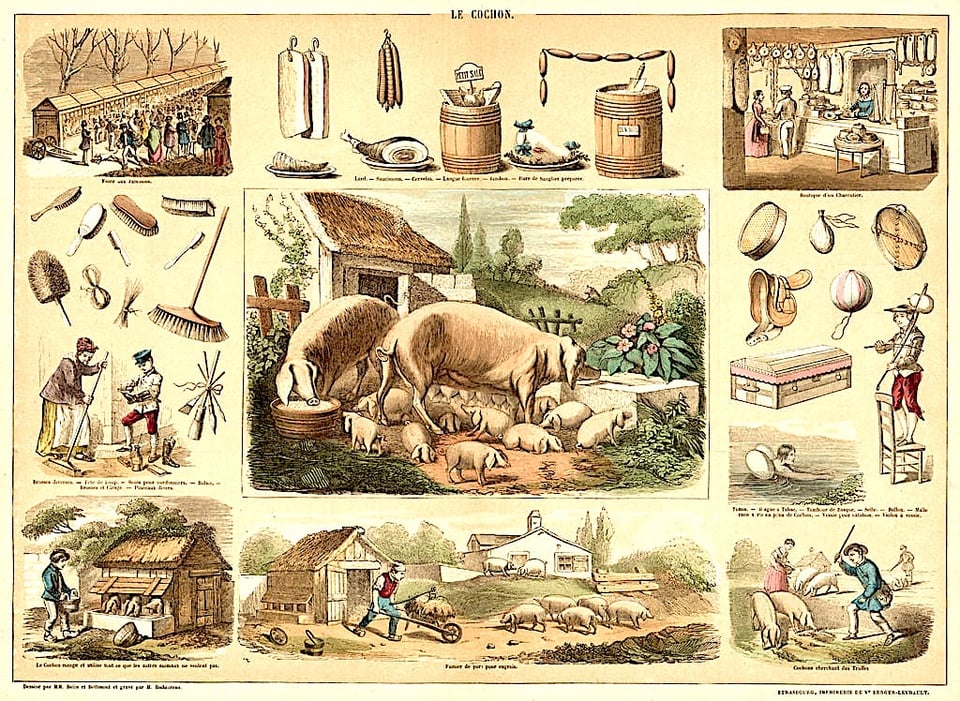

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where I, alongside my editor David Swanson, trip merrily through the bizarre and ever-mutating document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches. This week: in lieu of the ham and cheese and ham and egg sandwich respectively—which we skirted last week—a retrospective on the history, domestication, and consumption of the pig.

The first thing to note is a pig is a pig—or boar or swine—but its flesh, in English, is pork. This corresponds with other culinary linguistic quirks: a cow is beef when it’s on a plate, a sheep is mutton. Why? Because the nobles named it, and they’d invaded England under William the Conqueror and spoke French; porc, boeuf, mouton replaced swineflesh, cowflesh, sheepflesh. But the peasantry still herded the pigs; so they stayed swineherds and the swine stayed swine. (Ham has an old Germanic root—the back of the knee, which became the thigh, then the hock of an animal, so already this linguistic-stratification point, which was meant to be eloquent, is muddled. But maybe it was the peasants that did the butchering too, and the nobles that ate tout le porc).

The second thing to note is that humans and pigs came together in a rough process of domestication several times throughout prehistory, on several continents. Boars and peccaries developed the characteristic shorter snouts and smaller skulls that indicate breeding for docility in the archaeological record over and over—scientifically put, the move from sus scrofa to sus scrofa domesticus. This occurred independently and at thousands of years’ distance in the Near East, along the Yangtze, in Southeast Asia. In the words of Marc Essig, author of Lesser Beasts: a Snout to Tail History of the Humble Pig, which is the source for much of this column: “When something happens a half dozen times or more, it starts to take on an air of inevitability, as if the partnership between pigs and people had been rendered necessary by the nature of each.”

Men went out and caught and tamed wild herds of sheep and goats—prey animals—but pigs came to us, over and over. Being omnivorous, they ate our garbage and our shit, walking sanitation departments and snacks in one. A pig will eat just about anything and will in turn be eaten. This has been the case for much of human history, well into the nineteenth century, as in one census of Manhattan that saw approximately one pig for every five people on this small island; Charles Dickens’ stroll through the city was marred by the sight of rooting sows digging at the vast waste the people made. He might have saved his shock; there were pigs on the streets of England too.

In China the first evidence of pork consumption dates from some nine thousand years ago. “The character 家 (jia), which means both ‘home’ and ‘family’ in Chinese, was made some 3,500 years ago by adding the roof radical to the pig radical; essentially by putting a roof over a pig’s head,” notes China Dialogue. From China, too, stems a unique ornament that indicates the pig’s role for most of its—and humanity’s—history: a ceramic outhouse with a pigsty positioned underneath it. Pigs eat shit, and get fat; they produce shit, which fattens grainfields wonderfully; we eat their fat. The word “larder” comes from “lard” and all the associated products—sausage, cured ham, lardo—that come from the pig.

It has, for the most part, been a humble food and a poor one and even one prohibited, by religion and empire and the state, with some significant exceptions. The Romans loved pork above all, and concocted elaborate and obscene dishes—bloody udders, extracted wombs—and bred pure white suckling pigs for the princes of their great slave empire. When the Visigoths came the white pigs died but their hardy forest brethren, who ate nuts and roots and lizards and anything else in the forests, lived on.

In the high Medieval days boar-hunting (and boar consumption) was the province of nobles, who lanced the tusked beasts that fed on forest mast. The ancient Greeks disseminated the legend of the hunt for the Calydonian Boar, a mythic man-eater sent in vengeance by the hunt goddess Artemis to punish a king, and shot-through with an arrow by the huntress Atalanta. Not to be outdone, King Arthur hunted a mythic boar too, with the fabulous Welsh name Twrch Trwyth, aided by his great hound Cavall; he drove it from Ireland to Britain and cast it from the cliffs at Cornwall. Medieval cooks, aping Apicius of the Romans, sewed capons to pig haunches, creating fabulous heraldic beasts out of swine.

From these heroic heights the pig fell out of fashion; all those Proverbs and even New Testament execrations and curses—“pearls before swine” and Jesus casting demons into a drove of pigs. Still, they abided beside the human, sometimes on the margins and sometimes not: scavenger and scavenged, predator and prey. A smart, hardy, wiry animal, uncannily similar in some aspects of its anatomy: the pig and the human are twinned beings, parasitic, one twin perpetually consuming the other.

In the past, this had been a mostly intimate process: industrial-scale farming, and particularly its more brutal aspects, are quite recent. More often a pig would be fostered by hand on scraps and then slaughtered by way of a banner event of an agricultural year: the blood in autumn, the humanlike wail, and then the fatback laid in salt against the lean winters, or, in China, eaten in celebration of the Spring Festival. The pig was a family member and then you ate it and got a new piglet for the cottage. “Pigs must be killed, poor people must live,” says Arabella, after such a slaughter, in Thomas Hardy’s 1895 Jude the Obscure. Essig quotes a nineteenth-century American girl who cried on slaughter-day, then dipped her bread in pork gravy jubilantly the next evening, learning to live, she said, “in this world of compromises.”

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

Pigs were the mobile engines of American conquest: the Spanish—true masters of the porcine arts—brought them, let them breed wild in the Caribbean. They ate guavas and cassava; in North America they ate the good roots the Native Americans had harvested for millennia, until a chief begged respite. There was no respite. The pigs marched on, and when the great fields of maize raised their green banners across the Midwest it was chiefly in order to feed pigs (you could “hog down” a field by letting the pigs at it, husks and kernels and stalks alike) and to make whiskey. Mobile larders, more portable than corn, bushels on legs, compatriots of empire.

When pig-killing became big business, they named the great ramp that carried the beasts to the Chicago stockyards the Bridge of Sighs, after the bridge in Venice over which condemned prisoners were marched to execution. One last view before you die. Then yanked up, throat cut, boiled, bristles stripped for brushes, blood for sausages and Prussian Blue dye, hooves for glue, bones for buttons, gelatin, charcoal. Flesh for eating, by the rich sometimes, but mostly as ever by the poor.

Pigs are clever and they like beer. Their snouts are their primary interface with the world and they touch, root, snuffle, build nests with it. In the present age of mass agriculture they can do none of these things; most are not even provided with straw, the sows are caged and inseminated again and again, sore-raddled, unable even to fully turn in their crates. One animal-rights activist Essig quotes calls the meat aisle in the supermarket a “strip-lit morgue.” You can eat a thousand pork chops and never see a pig die. A thousand thousand ham sandwiches, ham and cheese, bacon cheeseburgers. They no longer eat the city waste or get kept by households in middens or sties. They live and die unseen.

The industrial alienation that culminates this story of twinned beings is curiously apposite. Never have we been so divorced from our land or ourselves, our lives strip-lit morgues of digital screens. It could make you run mad. It could make you strip to your skin, get bristly, run around rooting for acorns. How many millennia, how much convergent evolution, for it to come to this—the feedlot and its torment and squalor? How much do we owe to the things we will make die? A lot, I think. As much as we owe to ourselves.

I can’t believe it’ll stop here, in this monstrous alien place, where boar semen is sold to farmers who don’t even own the sows they impregnate, whose piglets grow monstrously, chemically big in months. I cannot believe this is the end of this story, our twinned story. It must go somewhere else: back out under the sky, hunter and hunted, murderer and victim, scavenger and scavenged. There is a better story, somewhere hiding in the constellations with the Calydonian Boar. Because swine is still swine, as it has always been, even if most of us are rich enough to dine on pork from time to time. What pearls I have, I will cast down, and let the swine take of them, and eat.

Add a comment: