Notable Sandwiches #139: Roti Bakar

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where my editor David Swanson and I trip merrily through Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches. This week, a delicious byproduct of brutal colonialism: the roti bakar.

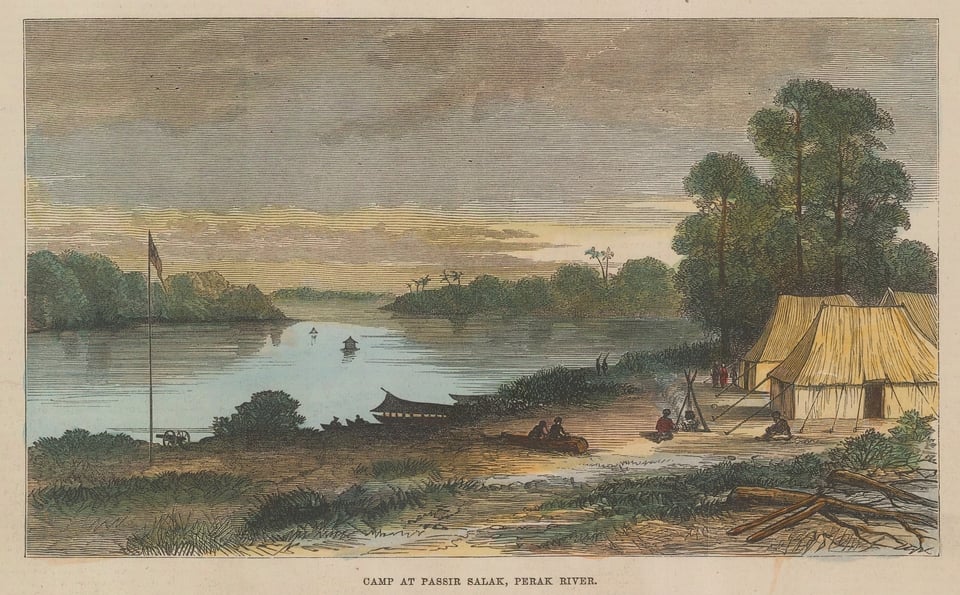

You can’t write about the Malaysian state of Perak—even about its local breakfast sandwich, roti bakar—without writing about tin. Roti bakar isn’t unique to Perak–you can find it across Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore–but the region’s particularly dramatic history of conquest, and current proliferation of coffee shops, makes it the ideal ground to illustrate the long and complex trail of history that underlies a relatively simple sandwich.

It's Perak's historical abundance of tin that gave rise to its role as a “shuttlecock” for empires, as a British imperial administrator put it. Tin was irresistible to traders and would-be conquerors, from the Portuguese to the Dutch to the British, and Perak’s reserves made the land, in turn, irresistible as well. Tin, malleable and easy to melt, goes so well in alloys: from bronze to pewter to electrical solder. No land and no people are uniquely malleable, but over the course of centuries, and empires, and squabbles, and the inevitable cultural detritus of conquest after conquest, it could be argued that the culture of Perak is a kind of alloy all its own.

From the 1640s—when the Dutch East India Company (VOC) ousted their local competition, the Portuguese Empire—onward, the Dutch used Perak tin to help consolidate their status as the world’s chief merchant empire. They also forced farmers in neighboring Indonesia, where the VOC reigned brutally for hundreds of years, to devote much of their land and labor to growing the non-native coffee plant as a cash crop. (The synonymity of Java with coffee is therefore an extended, and cruel, imperial joke.) Thanks to the VOC, Amsterdam became a global center of coffee and coffeeshop culture, and it spread; it was in Parisian cafés that the French Revolution was seeded, that the Enlightenment blossomed. During the same period, another Dutch signature, the characteristic blue-and-white ceramic known as Delftware, was born. Its signature coloration was achieved by using tin in the pottery glaze.

Nearly four hundred years after the initial Dutch conquest, the state capital of Perak, Ipoh, is known for its particularly vibrant kopitiam coffee culture. It’s the coffee capital of Malaysia—and at every good café, you can buy a roti bakar, a sandwich of grilled white bread. It’s often spread with kaya, a sweet, custardy coconut jam flavored with pandan leaves that give it a floral taste and a pale green tint. (Spencer Low, an amateur historian of the Portuguese influence on Asian culture, claims that kaya is a local variant on a Portuguese egg custard dessert; if so, a hyperlocal breakfast contains multiple empires.)

It’s not necessarily intuitive to draw a line between centuries of ruthless exploitation and a very pleasant breakfast sandwich, but the two are integrally connected, as bread and labor often are. Colonization and conquest are one of the oldest, if cruelest, human ways of spreading culture; and white bread is a European export, produced by native peoples to cater to the tastes of their colonizers. Even when Malaysia became free in 1957, European-style white bread remained, baked by locals and consumed by them in turn. The coffee-shop culture created by centuries of European habitation took on a Perak form at cafés like Ipoh’s Sin Yoon Loong, with marble tables and mint-green walls, serving white coffee and roti bakar kaya alongside salted softboiled eggs.

All of this is intricately mixed up in Perak’s history as a battleground of empires. “On the stage of Perak's modern history there have been many actors: the Malays, the Portuguese, the Achinese, the Dutch, the Bugis from Riau and Selangor, Siam and her vassal Kedah, and the British,” wrote two British colonial administrators, who published “A History of Perak” in the Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society in 1934. “At the back of all Perak history has been trade. Trade alone attracted the Europeans, an unassailable thirst for the purchase of tin and the sale of cloth.”

It started, though, with tin and conquest. Some of it was wooing, and some of it was blood, and most often, as in Perak, it was a combination of the two. In the 1640s, Perak was a suzerainty of the Aceh Sultanate, a Muslim empire that encompassed parts of today’s Indonesia and Malaysia. Dutch commercial power was on the rise, employing a campaign of bribery. The blood would come later, as it usually does.

But first a VOC head-merchant named Jan Dircxen Puijit lavished the Sultan of Perak, Muffazar Shah II, with a cargo of merchandise, a gift from the Dutch Governor of Malacca, who sought a full monopoly over the tin trade. In return, the Sultan presented Puijit with a gold dagger and a sword and an official residence and a new title. In the interim, he played for time. Burmese, Javanese, Chinese, and Indian merchants had long participated in the local tin trade; granting a monopoly would not be a simple matter, nor necessarily desirable. The Dutch came back with salt, with Dutch guilders and Spanish reals, and with four elephants (although one fell overboard).

“The Sultan still temporized. No monopoly of tin!,” A History of Perak declaims. “The Company got only ‘fair words and friendly faces.’”

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

But they had enough ships to blockade the ports of Aceh and Perak, and they did. They had enough funds to bribe as well as bully the trading partners and neighbors of Perak, and they did. “In 1648 sitting on a raised stool and guarded by three female lancers and six female musketeers the Susunan of Mataram, under Dutch pressure, issued a mandate ordaining public floggings for any of his people who sailed to Perak,” A History of Perak continues. The Sultan of Perak and the Queen of Aceh signed a treaty agreeing to a Dutch tin monopoly in 1650.

The VOC made steep demands, which the local leaders imposed by means of the corvee system of forced labor. The following year, 1651, the people of Perak rose up and murdered every VOC trader and representative in the province, in what the future governor of Dutch Malacca Balthasar Bort would call a “foul slaughter.” But, ultimately, more traders returned. Recognizing the limitations of the corvee system in times of drought and starvation, the Dutch ordered the Sultans to allow indentured Chinese laborers to work Perak’s mines in the late eighteenth century, according a recent history of the Kinta Valley by two Malaysian historians.

For a hundred and fifty years, a cycle of revolts, the renewal of monopoly treaties, and squabbling with the fading Aceh Empire or the rising British Empire—blockades, more uprisings, more treaties—ensured Dutch control. It was bloody. It involved both neighbors of Perak and neighbors of the Dutch; it involved more favors of gold daggers and ceremonial titles and bloody uprisings and colonial vengeance.

Dutch rule also gave rise to roti bakar, which developed in the Dutch East Indies as a practical way to use day-old bread—usually served with butter, Dutch cheeses, or condensed milk—as both a street food and a breakfast. You can buy roti bakar nearly anywhere in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. In Perak’s kopitiam coffee shops, a cup of Ipoh white coffee almost always has roti bakar as an accompaniment on the menu. White bread was European; the creative use of its leftovers, making the discarded delicious, was a local innovation of necessity.

Ultimately, the British ended Dutch brutality by taking it over for themselves, with the British East India Company muscling out the waning VOC in the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824. The Dutch may have receded in power, but tin was still a valuable commodity: tinned goods, named for the metal itself, had just come into vogue, and their ubiquity would only rise. The empire might have changed, but rapacity and monopoly did not, even as Perak was eventually enfolded in the British protectorate known as the Federated Malay States.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries there was something of a tin rush in Perak; British mining corporations brought in an influx of Chinese migrant labor, in the Kinta Valley and Larut and the rest of the region. They enabled the extraction and export of tons of tin, and eventually made up nearly one-third of the populace of Perak. These immigrants worked in the mines and everywhere else. They also pioneered a new kind of beverage, Ipoh white coffee, named for Perak’s capital, that serves as a crucial counterpoint to roti bakar. In 1937, two Chinese brothers, Poh Chew and Wong Poh Ting, introduced the coffee to the world at their kopitiam in Ipoh’s Old Town. The coffee beans are slow-roasted in margarine, offering a smooth, blond, highly caffeinated roast, and the drink is usually served with a froth of condensed milk—and roti bakar kaya.

These days, Ipoh is more famous for its cafés than its mines. Malaysia’s tin industry went from being the largest in the world to suffering a sharp decline after the worldwide collapse of tin prices in the 1980s. Still, every acre of the region has been shaped by the forces of conquest, acquisition, settlement, and migration that gave birth to roti bakar and the tin industry it fed for so long. Tin is soft and changeable, and can be combined with other metals in astounding ways. Walk down the street in Ipoh, order a roti bakar kaya with a white coffee, and experience another kind of alloy in a place where many cultures have intermingled, some by the sword and some by labor and some by habitation and some by happenstance. In that combination you’ll find a mix of the residue of baser human impulses with finer and enduring needs, to create something strong, and sweet, and all its own.

-

In this world of feh, the Sword and The Sandwich is a yay.

-

Thank you for this gem. Who wouldn't love an epic drama series centered around the VOC in Asia?

It wouldn't be PG, that much is certain. See also 'Nathaniel's Nutmeg' by Giles Milton, a narrative of the early 17th C conflict between Britain and the VOC over the Moluccas. Ghastly stuff.

-

Not the first delicious food to have problematic origins.

Add a comment: