Notable Sandwiches #137: Po' Boy

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where my editor David Swanson and I trip merrily through Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches. This week, a New Orleans favorite: the po’ boy.

Throughout America’s history there have been poor boys. Some of them are sandwiches.

In general, the rise of the sandwich, despite its purported aristocratic origins with a hard-gambling earl, has matched the rise of workers on the move. Its portability and self-contained nature—both protein and starch in one—makes it a workingman’s food, for the lunchpail or the street stall, to be eaten one-handed between shifts. In the nineteenth century, the sandwich powered factory labor; it fueled the hands that made the assembly line move, and crafted things, and dug things, and built things. In the twentieth century, as office jobs proliferated beyond the elite, the sandwich took its place as desk-side fare too.

But the sandwich, or at least its ubiquity, has also always been closely associated with labor: it’s the beau ideal of a working lunch, not a long and leisurely break. It’s neat and nourishing, and mostly doesn’t require refrigeration. You can take it down the mine or eat it between phone calls. It’s the food of work.

And it’s also, by extension, the food of the strike, mutual aid, protest, and solidarity with those who labor. So it’s fitting that one of America’s most iconic sandwiches—the po’ boy, a jewel in the crown of New Orleans cuisine—was born out of a strike, and the poor boys who withheld their labor.

Unlike a lot of legendary sandwiches, the po’ boy has a relatively straightforward genesis story. In July 1929, over New Orleans’ long, sultry summer, more than a thousand streetcar workers, members of the Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees of America Division No. 194, commenced a four-month strike. It was prolonged and vicious: the company brought down scabs from New York, and more than ten thousand New Orleanians gathered in the streets to watch strikers burn a streetcar driven by strikebreakers.

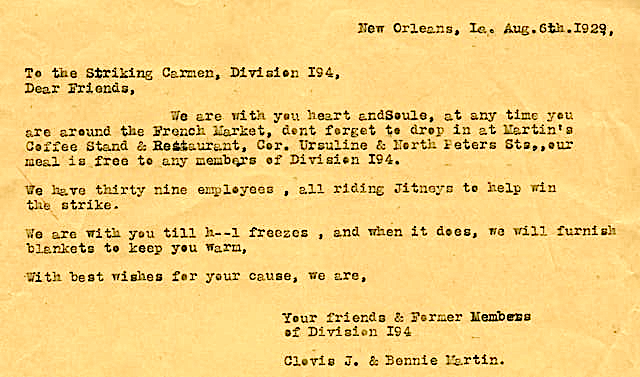

But spectacle alone, or even the abstract sympathy of crowds, can’t feed a family, let alone a thousand strikers. Enter restaurateur brothers Clovis and Bennie Martin, proprietors of a café in the French quarter. They published the following letter in August 1929, a month into the strike, just when zeal might be eroded by hunger:

To the Striking Carmen, Division 194,

Dear Friends,

We are with you heart and soule, at any time you are around the French Market, dont forget to drop in at Martin’s Coffee Stand & Restaurant, Cor. Ursuline & North Peters Sts., our meal is free to any members of Division 194.

We have thirty nine employees, all riding Jitneys to help win the strike.

We are with you till h--l freezes, and when it does, we will furnish blankets to keep you warm,

With best wishes for your cause, we are,

Your friends & Former Members of Division 194

Clovis J. & Bennie Martin.

In practice, they furnished roast beef sandwiches on the Crescent City’s characteristic French loaves. It was during this period that the sandwich earned the moniker “poor boy”—it was food for those poor boys, suffering as they struck their blow for labor rights. Eased, a bit, a sandwich at a time.

Post-strike, the sandwich has achieved both notoriety and variety. Today, it can be made with roast beef or fried shrimp, oysters or ham or catfish. What’s consistent, though, is the long loaf, crispy on the outside and soft and pliant within, “all dressed” with shredded lettuce, sliced tomato, and a surfeit of condiments. The Martin family maintains that they only ever called the sandwich the “poor boy”; its linguistic shift to the “po’ boy” is more an indication of Louisiana twang than anything else, a phonetic rendition of a sandwich tied to a time, cause, and place.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

The best po’ boys I’ve had were in New Orleans, naturally, and the goodness of the sandwich seemed to be tied to the sparseness of its surroundings. I recall eating a fried-shrimp po’ boy in a sandwich shop stark with fluorescent light, with stripped-bare little booths and plastic trays. And each bite was a revelation, of yielding bread and crisp fresh food straight from the shore.

Visiting New Orleans is the easiest way for an American to feel they’ve gone somewhere truly foreign without leaving the country. You can feel the French heritage of the place, the Gulf-facing melded culture of it all. In the summer, Spanish moss hangs from the trees, and Dixieland jazz syncopates in the streets alongside the bayou rhythms of zydeco, that unique style of Cajun-Creole music that features washboard and accordian alongside drums and guitar. (Zydeco, incidentally, also has an etymology rooted both in food and in phonetic dialect: the name of the genre comes from a phrase that made its way into a popular song, “Les haricots ne sont pas salés”—“the beans aren’t salted”—a local phrase for “times are hard.” It’s blues, that way. Through phonetic transcription of Cajun Louisiana French, “Les haricots” became “zydeco.” And in another unlooked-for synchronicity, the first zydeco record dates from the year of the strike: 1929.)

In New Orleans in the summer you walk and eat and drink and listen to music, and in the hot streets you feel like you’re in a exotic locale. (I’ve gone twice, with different lovers: the first trip was like a good dream, beignets and chicory coffee, crispy chicken at Little Dizzy’s, jazz in the French Quarter, strange graves, and big pink Hurricanes. The second trip: in winter, and with another lover; it rained, and he was a picky eater. There was nowhere to walk and nothing to eat. We didn’t last after that.)

The po’ boy shines in simple surroundings, though, not requiring the trappings of a Commander’s Palace or Galatoire’s or any trendy prix-fixe bistro. If the loaf is sturdy and the fillings plentiful, nothing further or more fanciful is required. It’s food for a poor boy, but it suits anyone. It was born to feed those who needed it, from heaven to hell and beyond its freezing.

It takes picketers to make a strike; confrontations with scabs; negotiators to work terms; action in the streets. But it also takes sustenance. Without bread, there can be no strike: the bakers and distributors are the backbone of any social movement, from the hot summer of burning streetcars to, a century later, those who provide meals to others fighting for justice on frigid city streets. Feeding a strike is the work of love and the fuel of necessity.

The things that make a sandwich suitable for the laborer—portability, durability, wholesomeness—make it ideal in aid as well. There will always be poor boys, and poor girls, and those who feed them. Nearly a century on from the great summer strike of 1929, it’s a lesson worth recalling: Solidarity can take a lot of forms, and some of them come pressed in a long French loaf, given freely with open hands to those who need it.

Add a comment: