Notable Sandwiches #136: Peanut Butter & Jelly

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where David & I traipse through the garden of earthly delights that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. We're switching things up a bit and speed-running to the end of the alphabet, selecting the most delectable and iconic dishes for each letter (in time for Tal to fulfill his book contract). But have no fear. We'll go back and fill in the ones we missed. Because the task of the sandwich chronicler, like Wikipedia itself, is ever-changing and infinite.

I don’t remember the first peanut butter and jelly sandwich I ever ate.

That doesn’t mean I didn’t eat them as a kid, but memory is a strange country, and mine is full of unexpected blank spaces, little terras incognita that sometimes stretch for years. I grew up in the pre-peanut-allergy-panic days of the ‘90s, and to have arrived at school, or survived through dinnertime after, without encountering this obligatory symbol of American childhood seems unlikely in the extreme. Not that I had a typical American childhood in any other way—no Christmas, no Saturday morning cartoons; yes halvah, and yes feeselach, chicken feet served in jelly, which I memorably ate at a friend’s house after school once, while the family’s parrot shrieked in outrage from a few feet away in the kitchen, as if offended on behalf of all avians.

That being said: I’ve surely eaten a peanut butter and jelly sandwich or two or two dozen in my time. I certainly enjoy them now as an adult, with petit-bourgeois flourishes: on sourdough, and with Bonne Maman apricot jam, or with a layer of fresh raspberries inserted between the peanut butter and the jelly. Sometimes you’re too tired to do more than assembly for a meal; the PB&J is so associated with childhood because it offers a direct answer to the perennial exhaustion of the caregiving parent, and a wholesome one besides.

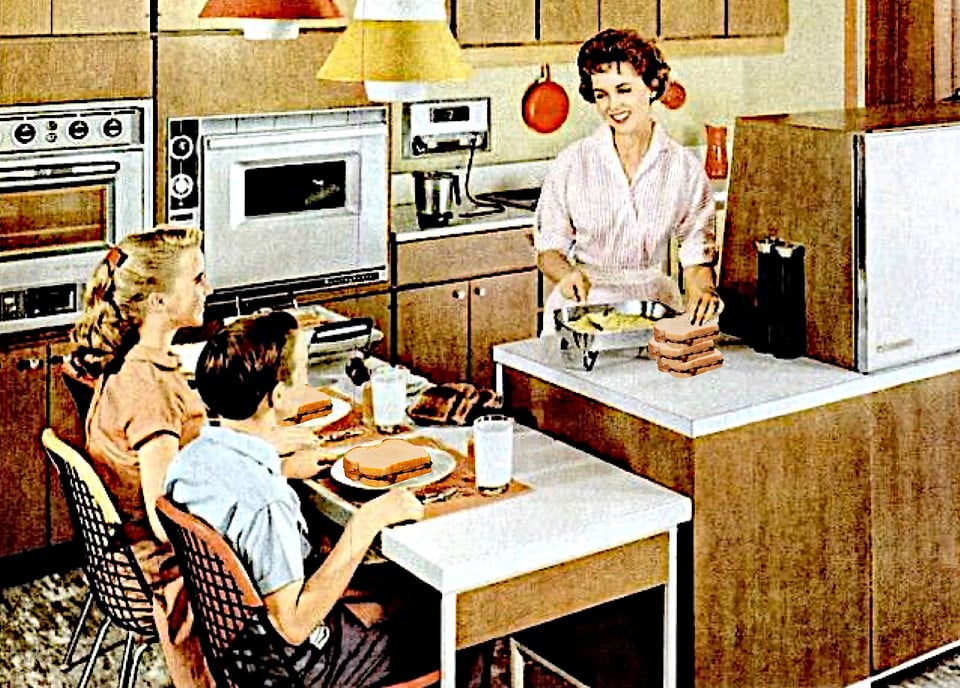

So that’s the mythos of the peanut butter and jelly sandwich: it’s an instant portal of nostalgia, something your mom made for you, easy and sweet, requiring nothing more than a butter knife and a few shelf-stable ingredients. It’s got strong gender and age associations. It’s a children’s food, with the subsidiary association with caretaking—which, in our patriarchal context, means motherhood and women’s work: in the kitchen creating picnics, making school lunches, wiping kids’ faces clean of sticky sandwich residue.

It’s also a notably American food: peanut butter in general is often the subject of some bafflement overseas, particularly in Europe, given its centrality in American cuisine. The historian Steve Estes of Sonoma State University argues that the peanut butter and jelly sandwich worked to bridge divides between public and private life, between parents and children, and across economic classes during its peak in the late twentieth century. That’s a heavy burden to place on a sandwich, but the PB&J’s iconic status suggests that it has performed at least some of these functions. Thus presented with an object that comes tidily wrapped in its own legend, the impetus of this project is to ask—why?

There are a number of separate questions bundled in here—why is the peanut butter and jelly sandwich so popular, why is it so associated with childhood, and when and how did it arrive at this stature? Rest assured I will provide you with my best stab at the answers. If any ancillary myths are punctured in the process, just know that I stand beside you in my own bemusement at these developments.

First: peanut butter. I was devastated to discover it wasn’t actually invented by George Washington Carver—besides documented evidence of the Aztecs making peanut pastes in the 1500s, one Marcellus G. Edson of Montreal patented the process of making paste from roasted peanuts in 1884. (This is not to discount Carver’s valiant work in proselytizing the peanut, subject of his pamphlet “How to Grow the Peanut: And 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption," although no. 37, peanut and liver, and no. 16, Swedish nut rolls, never attained the ubiquity of no. 59, peanut butter sandwiches.)

Carver’s well-publicized passion for the peanut had to do with its value as a nitrogen-fixing crop. He hoped to break up the monopoly of cotton, which rapidly depletes soil of its nutrients, and dedicated much of his life to agricultural research in aid of poor Black farmers in the South. Peanut butter—given a mainstream boost by Harvey Kellogg, who believed plant foods could calm the inflamed libidos of the impious public—had hit mass markets by the fin-de-siecle. By the turn of the twentieth century, it had become a sufficiently well-recognized ingredient to merit inclusion in cookbooks aimed at both the highbrow and the down-at-heel kitchenista.

The peanut butter and jelly sandwich itself makes its first appearance in a 1901 article by one Julia Davis Chandler in the Boston Cooking School Magazine—the Boston Cooking School being a somewhat menacing collective of women who proceeded to place a very white and very homogeneous stamp on American cuisine during the ensuing decades, first in New England and then throughout the country. Ms. Chandler, who wrote that she believed her recipe to be original, pitched the sandwich as an amuse-bouche for a high tea, suggesting pairing peanut paste with currant or crabapple jelly in “little sandwiches.”

By the 1910s, however, the sandwiches had both grown in size and reduced in social tone. In 1913, the New York Times suggested that sandwiches adorned with “jellies, nuts, peanuts” wrapped in paraffin paper could provide the solution to the “problem of the schoolboy’s lunch basket.” In 1921, PB&J technology made an important advance when hydrogenated peanut butter, a smooth, emulsified spread that didn’t require the home cook to hand-mix the separated peanut oil into the ground nut meat, was patented by one Joseph Rosefield, a California businessman who would go on to found the Skippy brand in the 1930s. A ready-made sandwich spread in a jar, alongside homemade preserves or the mass-produced jams and jellies that crowded store aisles in the early twentieth century: the ingredients for an icon were now in place.

But the PB&J didn’t obtain any sort of ubiquity until the Great Depression—and with it, an urgent need for shelf-stable, cheap, and easily obtainable protein. The specter of mass starvation led to an unprecedented drive—kickstarted in part by the women of the Boston Cooking School and their counterparts in the U.S. Bureau of Home Economics—to distribute food, particularly to schoolchildren. Peanut butter and jelly sandwiches were a regular feature of the “emergency kitchens” that emerged to feed hungry schoolchildren in New York City in the early 1930s. Later, as the New Deal rolled out free lunches at 14,000 schools across the country, peanut butter and jelly was firmly included in their rota. Cheap, nourishing, and not requiring refrigeration, peanut butter and jelly sandwiches also served another somewhat more sinister goal during the period: assimilation. Immigrant children, in particular, were urged to adapt to peanut butter and jelly in lieu of the sharper tastes of home-cooked foods. “Lessons in 'eating American,' it was thought, would not only breed good citizens but also improve the morale, scholarship, and health of the students,” write Jane Ziegelman and Andrew Coe in their masterpiece A Square Meal: A Culinary History of the Great Depression.

Peanut butter’s Americanness was cemented by another of the massive upheavals of the twentieth century: war. Jars of Skippy were included in military rations for troops in both the European and Pacific theaters, and the peanut butter sandwich (with or without jelly) made an appearance in army cookbooks for American GIs, according to Estes. On the home front, wartime meat rationing made peanut protein a practical option for both workers and schoolchildren.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

Peanut butter, yes: but not yet the PB&J. The sweetness and childlike associations of the sandwich made it, culturally, a feminine food, fare not suited for the grown man. In the 1940s, workingmen’s peanut butter was paired with a staggering array of dance partners, from pickles to prunes to raw cabbage. One Yonkers man told the New York Times in 1943 that he considered peanut butter and mustard “a real he-man sandwich.” Gender is an inescapable panopticon, but it says something about the punishing nature of self-imposed masculinity that the PB&M never quite took off.

So what made the PB&J take a flying leap from Depression handout menus and faut de mieux lunches scorned by manly men to centrality in the national image of domestic bliss? The answer lies, as it often does, with nostalgia, no matter what the rose tint of the image of childhood obscures. By the 1950s, a mania for processed and ready-to-eat foods—the generation that embraced aspic with both hands—prevailed in a newly prosperous postwar America. Coupled with a smothering cult of domestic perfection among housewives, the era of the Baby Boom created the preconditions for a howling need for an easy-to-prepare sandwich to fill the household assembly line.

The peanut butter sandwich as symbol for domestic drudgery appears in the very first paragraph of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, the book that sought to draw out and explicate the poison of housewifely malaise. “Each suburban wife struggled with it alone,” Friedan wrote in 1963. “As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night-she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—‘Is this all?’”

There were a lot of children of the Baby Boom, though, who remembered those peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. Who remembered them in picnic hampers, and bicycling home from school at the lunch hour to consume them with milk. Jerry Mathers, who played the title character in TV’s domestic-perfection fantasy Leave it to Beaver, told the press that he ate a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and a glass of milk every day for lunch, on set or off of it. Thus, in a mere twenty years, the PB&J became a metonym for Arcadia, for childhood innocence.

Boomers carried PB&Js out of childhood into their era of protest, against Vietnam and for Civil Rights, squashy and familiar packets of protein at a price point accessible to both the poor and the middle-class suburban kids taking to the streets for change and justice. And when those children turned youthful protesters became the parents they despised—the “mothers and fathers/throughout the land” of Bob Dylan’s anthem “The Times They Are a-Changin’”—they began both to criticize what they couldn’t understand, and to serve peanut butter and jelly sandwiches to their own kids in turn.

A subsequent shift away from processed foods, along with a documented dramatic rise in peanut allergies (which more than tripled between 1997 and 2008), threatened the supremacy of the PB&J among school lunches, although it’s more a case of down but not out. You can’t fully erase an icon. Looking back over a century-plus of building the lore around a sandwich, from its origins as a high-tea curiosity to its current place as both a locus of nostalgia and a convenience for parents, there’s a clear set of winners that emerge. The teachers and home economists of the 1930s, who sought, while giving out school lunches, to impose a culinary homogeneity on their immigrant students, succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. By including the peanut butter and jelly sandwich as part of what it meant to “eat American,” they shaped that meaning, and in the process created generations’ worth of eaters who centralized it, unquestioned.

And that’s how you create a myth: you assert it boldly and serve it to those who are too young or too hungry to be critical. It may be a delicious thing you’ve made, and this one is. Still, it’s both a cautionary tale and a symbol in itself: of how we make myths, and of what ingredients—from desperation to innovation to gendered labor to immigrant assimilation—they are made. It’s always worth examining the sites of our nostalgia; to ask who made the madeleine we recall through the gauzy mist of time and love, and why, and when. It may give us pause to do so, but unexamined myths can ossify into undue meaning. In any case, hunger will always win out, and this sandwich offers a smooth, sweet answer, one just as loaded with history and its ambiguities as it is with delight.

-

I loved this sandwich history. Remembering assembly lines in the kitchen for 6 children at lunchtime when I was growing up (the meals were always cereal for breakfast and PBJ for lunch) made this a delightful read. I'm a big fan and this article brought a smile from me and a welcome distraction from focusing on current events. Thank you!

-

One of the best meals I've ever had was a PB&J on a bagel, handed to me by a street medic after I got out of jail for a protest. Exactly perfect.

-

I find amusing the notion of the gendered peanut butter sandwich. I am not a big fan of PB&J, but one of my favorite sandwiches is peanut butter and kimchi on whole wheat bread, preferably whole wheat pita bread. And yeah, my pronouns are he/him...

-

There are apparently a subset of PB&J fans who think you have to put peanut butter on both slices of bread, with jelly in the middle, to avoid the jelly soaking through the bread. To which I can only comment, if jelly soaking through the bread is an issue for you, you don't need more peanut butter, you need better bread.

Interesting! This is like the scone cream tea discourse in Britain. (Just in case it needs clarified, a scone is a soft sweetish bun, sort of halfway before bread and cake, which is cut in half horizontally) There's a fierce disdain between those who think you put jam on the cut surfaces of the scone, then smear thick cream on top and those who think you put the cream on first then drop jam on top. The latter is correct IMO! Because the fat of the cream acts like butter and stops the jam soaking into the soft surface of the scone

Not 'before'. I mean 'between'.

-

As a British person, this sandwich is the stuff of myth for me. And this exploration of it is fascinating!

A prosaic question, if I may. Are there preferred flavours of jelly ( what we call jam) to make it canonical, or is it a free-for-all?

This is one American’s opinion, but I’d say grape jelly. Strawberry jam comes second. Anything else becomes esoteric. Black currant preserves would work, but it’s uncommon here.

Thank you! Very interesting, especially as I've never heard of grape jelly!

-

I tried the peanut butter and mustard sandwich, well half of one because the bottle of sriracha next to it also demanded a test. Eh, it's all right, better than just peanut butter by itself.

Add a comment: