Notable Sandwiches #135: Patty Melt

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where David and I trip merrily through Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week, a hamburger in an unexpected presentation: the patty melt. Also, an administrative note: I’m Tal now, he/him, a trans man, as reflected in the byline; and that may or may not have influenced this week’s unnecessarily dramatic column.

In 1916, a cook named Louis Anderson finally made enough money slinging Hamburg steak sandwiches around Wichita, Kansas, to open up his own premises, in a former shoe-shine stand. Hamburg steak sandwiches, or hamburgers to the colloquially inclined, had already been popular for a few decades. The combination of chopped beef and onion, cooked on the quick at lunch stands and by street vendors, were a cheap and practical meal for hungry workers on their way to factories, and had been since at least the 1870s. Anderson’s innovation—disputed as all elements of the hamburger’s origin are disputed, because food firsts make money and myths demand genesis—was to level up from the soggy, easily separated slices of bread, and serve his hamburgers on sturdy buns custom-fit for the purpose. (It’s also disputed whether Anderson actually invented the hamburger bun; what’s not disputed is that he, in popularizing it, is irrevocably wedded to its metastasis across the world.)

It would have been easy for Anderson to be lost in the luncheonettes of history, or indeed the Midwest, which—having an abundance of cows back then—faced a fierce race among those innovating how to serve it. According to Hamburger: A Global History, by Andrew Smith, the real key to Anderson’s success—and the disproportionate impact he had on the burger’s image in America—was quintessentially American in and of itself: he hired a really good image guy. This was Edgar Ingram, an insurance salesman and estate agent, who was ready to do battle with the unsavory image of beef created in the wake of Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle, which was intended to rouse ire about labor but really made every American horrified by their own ground meat.

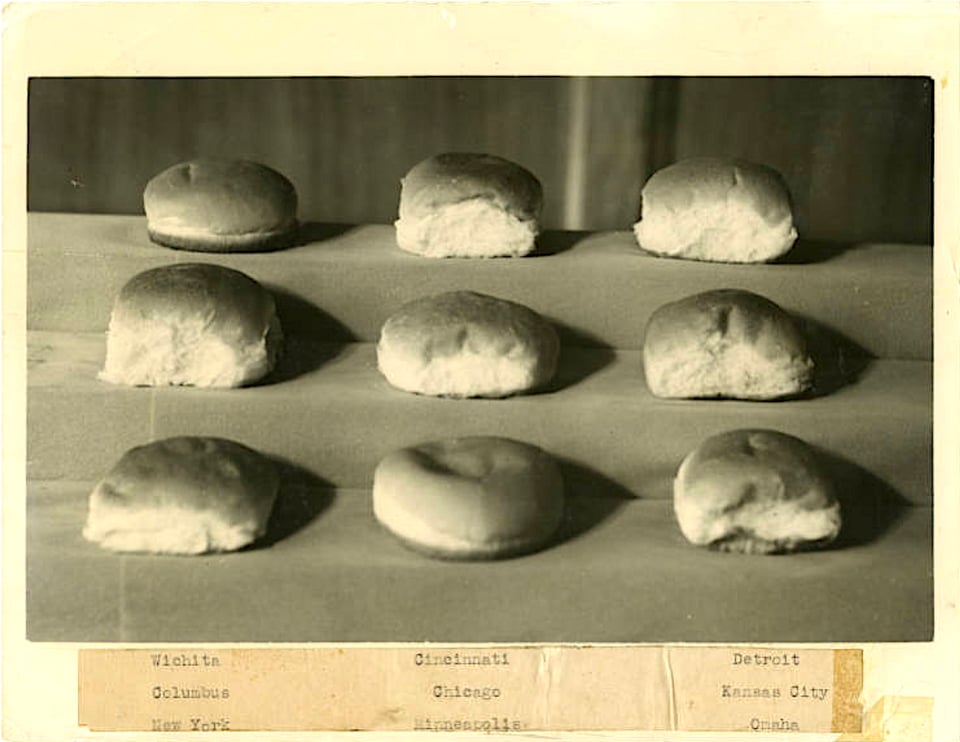

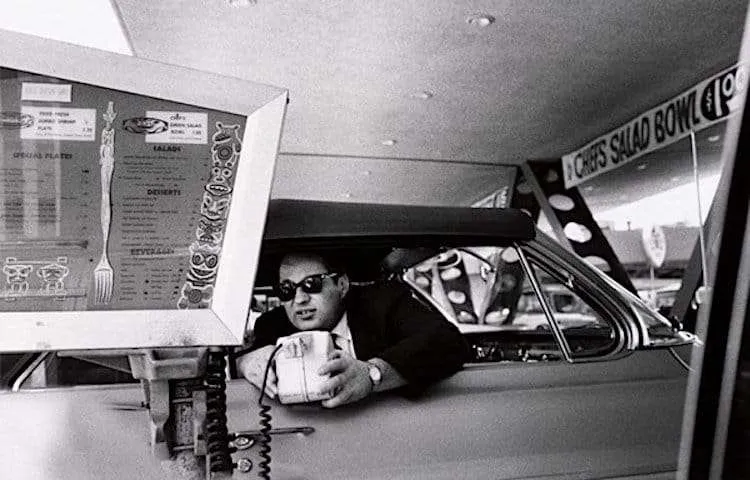

The resulting joint venture, founded in 1921, was dubbed “White Castle,” and its dual advantages were pristine, clean premises—all white with the grill hypervisible—and a ruthless uniformity. In this rapidly expanding empire, you could expect the same burgers, on the same buns, in Kansas, Omaha, St. Louis, Detroit, Minneapolis, even New York. “Buy ‘em by the sack” was the slogan; White Castle thrived throughout the Depression, selling forty million burgers a year. In the process they generated competitors and off-brand clones and—inadvertently or not—an ironclad public image of what a burger should be: a ground-beef patty between two custom-made buns, optimized for portability, for expense, and for a wholesome and uniform image that enabled the customer’s mind to be at ease, knowing that what he’d chosen would be what he’d eat, and it would be the same, every time.

That uniformity puts the mind at ease was hardly the brainchild of Edgar Ingram, nor any other fast-food chain. That’s half the battle in any life, really: that you’re following patterns, that you know what’s laid out before you, what’s expected of you. That you’re born into a life that has a set of expectations, and you, year by year and decade by decade, fill it out. Wife, kids, church (or synagogue or mosque); house; job; mortgage; success by whatever definition, of the mind or the bank account or hopefully both; that your parents will be pleased and prideful about it all. It’s a lot to ask of life, really, but it’s also the expectation you were born to fulfill, a life as sensical and neat and image-perfect as a hamburger on a plate. With sesame seeds on top and a pickle. Birth the top bun and death the bottom and everything in between neat, orderly, uniform from New Bedford to San Diego.

That the pattern of this kind of life was dreamed up as much by the insurance salesmen of the world as it was by any truth of nature or innate instinct goes without saying. That’s the point of this kind of life, of striving to fulfill it: not saying all the things that go without saying; not having to. When you fit the mold you were made for, you can let questions go like so many breaths, and they don’t multiply, don’t grow barbed. Your life goes by in a normal fashion, a choice and its expected outcome coupled seamlessly, ordered from a predetermined menu.

But here at the Sword and the Sandwich we passed the hamburger a long time ago (in a lackluster column reliant mostly on outsourced nostalgia) and have stumbled forward to the patty melt. In many ways it’s a reversion to the pre-White Castle days. The haphazard slapdash hamburger-stand scenarios of the 1870s, when chopped steak and onion of any or dubious provenance was made on the fly for the hungry. No standards, no image, no uniform buns: just bread, steak, hunger, heat. The very fact that the patty melt requires its own origin story—separate entry on Wikipedia, separate essay—is evidence of the conquest of the bun. Of the hamburger-as-ideal, the insurance-man’s image becoming an uncontested icon, a simple form from which any flourishes are cutesy subversion, not questioning the dominion of the overall model.

The patty melt is its own thing, though. Invented in the 1940s—this is less contested than the origins of the hamburger itself—by a San Francisco restaurateur named Tiny Naylor, the patty melt is served on rye, with Swiss cheese and caramelized onions. Its fortunes rose alongside its inventors, as Naylor’s restaurant empire extended to Southern California and roller-skating waitresses. Thus the retrofitting of the patty melt took on its own set of expectations, its own standardization, although patty melts (as viewed through a delivery app in my New York neighborhood) are a bit less rigid in this regard. You can get one, for example, with gruyere and aioli, or cheddar, or served on Texas toast, or with American cheese, or even, perplexingly, on a hamburger bun (the “patty melt burger”). The caramelized onions do seem to be non-negotiable, though. For which I can only be glad.

Still: even if you know and love the patty melt you know it’s not an icon in the same way. It isn’t predestined for anyone; it isn’t the unquestioned choice at any time; each midcentury-style patty melt may be alike on rye, but every nouveau patty melt is served in its own way. The patty melt leaves room for the kind of questions that set in when you realize you don’t fit the perfect mold, the one you were born for. Where you don’t fit on a bun, even if you don’t know why yet. When you have questions and the questions grow and fester and, effortlessly as rusting, you rot out of the life plan set for you; the one you set for yourself and tried to live up to. No emoji exists of the life you want, no predetermined option. There is no clear road to walk along once you decide to veer off the path of the expected, once you’re off-menu, off-road, along the steep and stony path of self-will.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

Out here, beyond the beau ideal, the constellations are unfamiliar, a strange place not on any map. There is no predictable shape: there are no readymade guidelines. You’ve shucked the burger, re-embraced the sloppy and indeterminate nature of bread. You’ve reverted to earlier and more primal methods of determining things: who you are, what you want, beyond expectations and good choices (for externally dependent values of good, and choices). It’s a painful thing to come to grips to; and some people who loved you when you fit, or tried to fit, or let them think you were trying, will not love you anymore. They want to know that what they order will be orderly and will not present any undue challenge. They want to pick from a menu and know that what they’ve gotten is what they wanted; they order their lives that way, and want that for you, too, and sometimes couch it as worry rather than overt hostility. Because it is frightening here in unknown territory; and they want you back in a warm and orderly place, even if you must lop off pieces of yourself to fit into the round plump mold of what goodness ought to be.

Still. There’s warmth here, there’s nourishment here, richer than any you’ve known. In the undiscovered hill country of self-discovery, of learning how to say all the things that once went without saying, of your very voice changing timbre and your body changing too, at the precipice of midlife, you know this: it will be harder now, but more vivid too, and new. Rich as Swiss on rye, sweet as golden onion left to mellow on the grill, and yours, the way nothing, til now, has ever really been.

-

Congratulations on a superb letter and on your continuing adventure. The way home is as always through the wilderness.

-

Delicious as always, Tal <3

-

God bless & good luck, Tal. Love the sandwich lore!

-

I usually only cry over beef that’s on my plate. Mazel, my friend. This is a good one.

-

I’m so happy for you. I wish you the best of all possible worlds.

-

As a trans woman living abroad and transitioning along multiple axes, I can’t tell you what a joy it is to have your insights in my inbox. Thank you for this one! From one patty melt to another, 🫂

-

Congratulations! And thank you for this. I have often found myself patty-melt-curious and didn't know I needed to tie my love of Ill Communication to them. What a world. Keep up the good work, Tal.

-

Mazel tov from a genderqueer trans masc fan I'm veganish so I identify as a soy boy melt, myself ;-)

Add a comment: