Notable Sandwiches #133 & #134: Pasty Barm & Pattie Butty

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where we trip merrily through the bizarre and mutable document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week, David takes a look at two carb-loaded Northern British favorites. — Tal

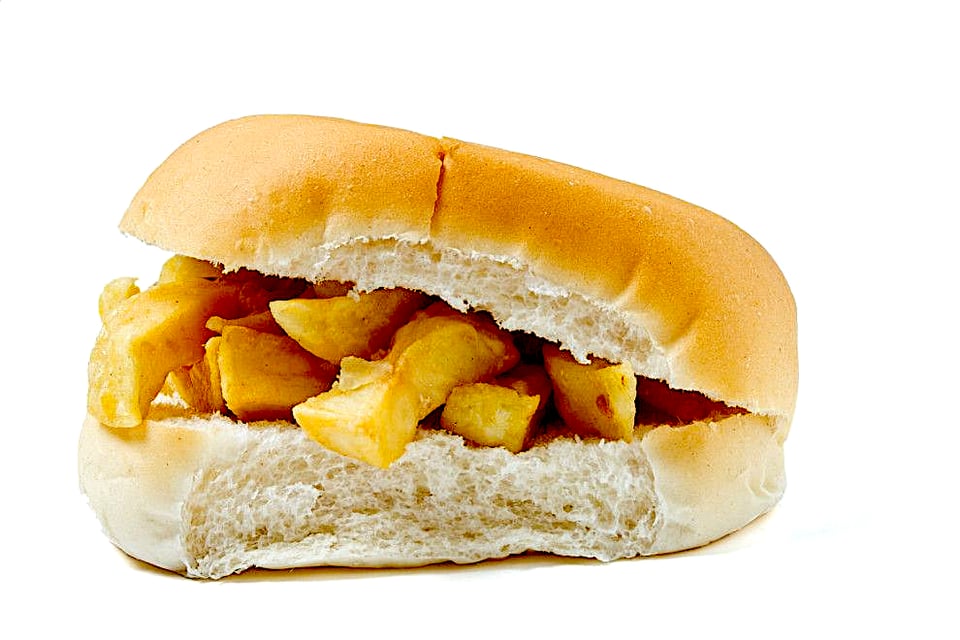

One of the challenges in reaching the back half of Wikipedia’s list of sandwiches is that entries start to echo. For this week, Tal and I had decided to combine the next two sandwiches on the list—the pasty barm and the pattie butty—because they are both examples of that Northern British specialty, the carb on carb. A pasty barm is a Cornish-style pasty on a roll; a pattie butty is a fried potato patty on roll. These are old foods. The first written record of pasties—hand-held, turnover-style meat-and-vegetable pies—comes from the Patent Rolls of Henry III in 1238. The pattie’s existence is less-well documented, but fried potato patties in one form or another can be found in countless cultures—if for some reason you were tempted to eat a latke on a roll last week, congratulations, you’ve essentially had a pattie butty.

In sandwich form, both were conceived by hungry, working-class denizens of Northern England—Bolton in the case of the pasty barm, Hull for the pattie butty. Now If you’ve been reading this column long enough, you may recognize this as well trodden ground. The pasty barm (meat pie on a roll) is a first cousin of the Glasgow Oyster (meat pie on a roll), while the pattie butty (fried potato on a roll) is a first cousin of the chip butty (fried potato on a roll). All four are members of the very particular, Northern British carb-on-carb sandwich family. So, on this holiday weekend, rather than simply rehash material we’ve already covered, we’re going a step further and reprinting those previous essays in full.

NOTABLE SANDWICH #40: THE CHIP BUTTY

September 30, 2022

September has been a rough month for the British, what with the death of Her Majesty, a brand-new government dead on arrival, and the collapse of the pound. So, in hindsight, it may have been an inauspicious time for Steve Albini to troll the entire United Kingdom. A Chicago-based punk rock luminary, Albini is almost as well known for his lovably cantankerous persona as he is for producing seminal albums for Nirvana, the Pixies, PJ Harvey, and more. So, when Albini unleashed an attack on an icon of British culture that’s trashier than the Queen but nearly as beloved, he must have known he was treading into dangerous territory.

Gonna do some chip butty tweets. For non UK people, a chip butty is a bap (roll, like a hamburger bun) with some chips (french fries) and a kind of watery fake mayonnaise they call (ugh) "salad cream." This is their sandwich, they eat this. Okay ready?

— regular steve albini (@electricalWSOP) September 15, 2022

He then proceeded to liken the sandwich to penguin meat. The responses—almost a thousand—came quickly. Many castigated Albini for his description: a “butty” should be made with “butter” on two slices of bread, or even one slice folded in half, but not on a bap; and, by the way, a bap is not a hamburger bun; and chips are not the same as french fries; and salad cream—salad cream!?!—should never enter the equation. Albini got the message, and less than an hour after his first ill-advised tweet, he apologized: “I’m leaving the chip butty thread up where I’m getting roasted, I deserve it. I live in a city that reveres hot dogs, I shouldn't be picking fights over proletarian fare.”

As the existence of this very newsletter attests—and as we’ve covered in previous installments—people all over the world take their sandwiches extremely seriously. Maybe too seriously. But the British affection for the chip butty speaks to a deep-rooted, Hobbit-like affinity for simple comforts; a (questionable) nostalgia for a time when the nation really did rule the waves; and a persistent self-consciousness over the quality of the national cuisine. Lauren Pascal, a Manchester D.J. who replied to Albini’s thread, put it this way: “Sorry to sound pro-British at a time where Brits are being especially embarrassing, but the only people who slag off chip butties are those who haven’t tried one. Yes, British food is largely not good. Yes we are joyless weirdos. But don’t be bringing the butties into it”

Here is where I must confess that, despite holding British citizenship, I am among those who has never eaten a chip butty. Like most university students in the U.K., I was well-acquainted with my local chip shop, but I was never tempted to eat mine in sandwich form—it was usually a haddock supper for me, with the occasional deep-fried black pudding if I was feeling particularly reckless. So, unlike the cheese and pickle—another iconic working-class British comfort food—the chip butty never entered my dietary rotation. But I get it. While the very notion originally struck me as being both mildly preposterous (carbs on carbs?) and somehow quintessentially British (they love their potatoes!) I now understand the fuss.

Despite its ubiquity, of course, the potato is no more native to the British Isles than the tomato is to Italy. The primary staple of the pre-Columbian Inca empire, the formidable solanum tuberosum been cultivated in the Andes for nearly 10,000 years. But the potato only made it to Britain in the late 16th Century—courtesy of Sir Francis Drake, or maybe Sir Walter Raleigh—and it was several centuries before it worked its way into European cuisine. Initially feared as poisonous—one nickname was “devil’s apple”—the potato was eventually standard fare for the aristocracy and peasantry alike. An acre of potatoes provided three times the nutrition as an acre of grain, and it was adaptable to a wide variety of climates and soils. Louis XVI and Frederick the Great promoted the vegetable in France and Prussia, respectively. In the 16th century, Basque sailors had introduced the potato to Ireland, and by the mid-19th century the island’s population had grown from 1.4 million to over 8 million. (Of course, the reliance on a single staple had devastating consequences when a blight in the 1840s spoiled the crop; roughly a million Irishmen and women starved, and more than a million fled the island.)

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

On the brighter side, someone along the way came up with the idea of deep-frying pieces of potato, and took the first step on the path to the chip, the frite, the french fry. Who specifically deserves credit is another matter. The French naturally claim it, but in Belgium—where “frites” are treated like a precious national resource—they dispute that notion, claiming that “french fry” is a misnomer, referring to the method of preparation (“french-cut” vegetables are sliced into sticks) rather than the geographic origin of the recipe.

Paul Ilegems, Belgian fried-potato evangelist and founder of the Frietmuseum in Bruges, offers two possible origin stories, both seemingly apocryphal. One legend attributes the invention to St. Teresa of Ávila. In a l577 letter to the Superior of the Convent of the Carmen in Seville, Teresa offers thanks for a recent shipment of supplies: “I received your letter, and with it the potatoes, the barrel and seven lemons. Everything arrived in good shape.” If that’s the extent of the evidence, I remain skeptical. According to the other (slightly) more convincing tale, in 1680 the River Meuse in Belgium froze over, depriving a local community near Liege of the tiny fish they would fry for sustenance. So they substituted strips of potato in roughly the same size and shape as the fish, and deep fried those instead.

Whatever the truth, by the 19th century the “chip” as we know it was a familiar British treat. In A Tale of Two Cities, from 1859, Charles Dickens was the first to use the term on record, referring to “husky chips of potatoes, fried with some reluctant drops of oil.” London’s first fish and chip shop was opened four years later by Joseph Malin, a Jewish immigrant living in the East End. That same year, a certain Mr. Lees began selling fried fish and chips out of a wooden stall in Mossely, outside Manchester. Soon, he was stuffing the fries into a barm (or roll) and selling them to a hungry populace adjusting to life in the industrial revolution. As the British economy struggled through the Long Depression of the late 19th century, the appeal of cheap, filling food increased, and chip culture took off. (As a proud Scotsman, I should note that the Dundee City Council has also laid claim to the chip’s origin, stating that “… in the 1870s, that glory of British gastronomy—the chip—was first sold by Belgian immigrant Edward De Gernier in the city's Greenmarket.”)

Today, the U.K. is home to some 10,500 chip shops, and it’s a safe bet that you can get a butty at any of them—though there may be some regional variations. In the Black Country they specialize in “orange chips.” Elsewhere, there are ethnic twists: in Liverpool, you can get Chinese “salt & pepper everything chips”; in Newcastle they sell chips smothered in bolognese sauce; and in the Manchester suburb of Rochdale the “International Chippy” sells theirs swimming in South Asian spices. While salt and vinegar remain the standard seasoning, there are those who prefer a lashing of gravy, curry, brown sauce, or a dollop of mushy peas. (Don’t get us started on “smack barm, pey wet.”)

In recent years, despite its status as a working-class standard, the chip butty has inevitably been given the gourmet treatment. Michelin-starred chef Paul Ainsworth serves an upscale version at his restaurant in Cornwall, featuring triple-cooked chips, Cornish sea salt, aioli, and aged parmesan on sourdough bread. In 2018, irascible food critic Jay Raynour praised the elevated butty at The Duke of Richmond in Hackney, “a palm-sized, golden-glazed bun, filled with mayonnaise-bound white crabmeat, the crunch of lightly pickled samphire and, finally, a fistful of still hot, still crisp chips.”

Other top chefs have no less reverence for the sandwich, but prefer it simple. Marco Pierre White, arguably the most influential chef in British history, calls the chip butty among his favorite dishes—but as far as he’s concerned they don’t need any elevating. “I have very working class tastes from growing up on a council estate. I love a chip butty but it has to be made with white bread, Mother’s Pride in the old days,” he said in 2017. “Plenty of butter and salt and vinegar on the chip shop chips. The bread takes on the same texture as the potato and it’s just delicious.” He nearly convinced Anthony Bourdain of the beauty of the butty.

A few years ago, Burger King made news when word got out that they were developing a “French Fry Sandwich” for their New Zealand market. As far as I can tell, the phenomenon of fries (or chips) as the primary ingredient in a sandwich is a foreign concept in the United States, though Primanti Brothers in Pittsburgh is renowned for stuffing their sandwiches with just about anything you can imagine, fries included. But we don’t have the same carb-on-carb culture as Britain, where, in addition to the chip butty, beans on toast is an enduring favorite, and the “pot noodle sandwich” is a thing that people actually eat. (Fear not: we’ll be addressing the “crisp butty” in the future.)

It isn’t only master chefs and working stiffs who appreciate the chip butty. Just this week, the British-born actress Naomi Watts celebrated her birthday with a chip butty made by her son:

|

Because this is 2022, Watt’s birthday post was deemed newsworthy, with the Daily Mail sniffily noting that her butty was served on a hamburger bun rather than bread, and used thin-cut french fries instead of thick-cut chips. Who knows what they might have said had she included salad cream?

Which brings us back to Steve Albini. Where, I wonder, did this favored son of Chicago learn about the chip butty? Albini has played in a number of bands that played shows in the U.K. And he estimates that he’s worked on several thousand albums over the years, so it’s no surprise that he’s collaborated with numerous British musicians who might have introduced him to the sandwich, including Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, PJ Harvey, and Pulp frontman Jarvis Cocker. That’s who gets my vote. Page and Harvey are both from the South, and Plant is from the Midlands, but Cocker is from Sheffield in the North. That’s proper butty country.

And while Cocker and his band may be Sheffield’s greatest musical export, the city is also home to the Arctic Monkeys, Human League, Def Leppard, and … “The Greasy Chip Butty Song,” official anthem of Sheffield United Football Club, founded in 1889. Set to the melody of John Denver’s “Annie,” the song is a checklist of Sheffield’s simple pleasures.

“You fill up my senses/ Like a gallon of Magnet/ Like a packet of Woodbines/ Like a good pinch of snuff/ Like a night out in Sheffield/ Like a greasy chip butty/ Like Sheffield United/ Come fill me again”

With its references to local ale and cigarette brands and a celebration of pub life—in addition to the titular “greasy chip butty”—this must be the least healthy sports song in history. According to legend, the anthem was written in the doldrums of Margaret Thatcher’s eighties economy, when a rapacious Tory government was wreaking economic devastation on Britain’s working class. Does that sound familiar? Last week the Daily Mail reported that—thanks to the rising costs of fish and fuel—the price of a fish and chip supper could reach more than £20. All this month, headlines across the U.K. have warned that the current crisis could be an extinction-level event for the country’s chippy culture. But “cheap as chips” is an old British idiom, and as bad as things get, a chip butty will always be amongst the cheapest, most filling, and most comforting offerings available. And given how this autumn has gone so far, if ever the British need a collective helping of comfort, this is the season. So, to my British bretheren: Good luck, Godspeed, and God save the chip butty.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

NOTABLE SANDWICHES #74: GLASGOW OYSTER

October 27, 2023

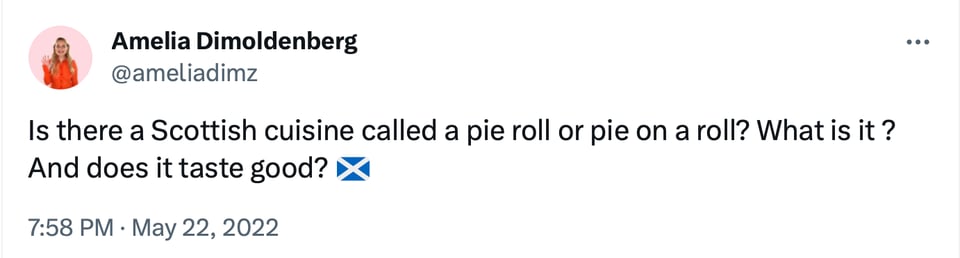

Last year, when British YouTube sensation Amelia Dimoldenberg asked her twitter followers about a seemingly simple sandwich, she could hardly have anticipated the response. To her first question, there was universal agreement: Oh, yes, it most certainly exists (although to call it “a Scottish cuisine” might be stretching things.) To the third question, regarding the taste, there was further agreement (“aye they taste fucking class ameel.” That’s a rave in Scots.) But as to the middle question—“What is it?”— there was little consensus beyond the constituent ingredients involved:

“Its called a ‘roll and pie’ or ‘pie and roll’ depending where in scotland, and its a scotch pie in a (normally buttered) roll...worth a try”

“I live in Lancashire and heard someone call it a growler”

“It’s called a piece and pie!”

“Roll 'n peh, its an aye from me”

“Also known as a Ballingry Big Mac. Heaven”

“The Highlanders are trying to steal the fine Lancashire dish of the Wigan kebab.”

“A Glasgow Oyster and it's magical.”

This final appellation—in which the roll is an oyster shell, and the pie a pearl—has the honor of representing the “pie roll” genus in Wikipedia’s sandwich taxonomy.

In Scotland and Northern England the meat pie is something between a staple and a delicacy: a seemingly humble comestible that’s treated with reverence. And it would seem that in separate communities across this swath of Britain, the notion arose that enveloping this staple/delicacy in a well-buttered roll might yield something greater than the sum of its parts. Multiple discovery is a concept this newsletter has explored before. “Whether we’re talking about science or sandwiches,” I wrote last year. “this tendency of inventions to arise—in parallel at the right time, among disparate minds—does not exclude their provenance from fierce contention.”

Generally the debate centers around claims of creation: was the French Dip invented at Philippe or Cole's? Where did the first Cuban sandwich appear, Tampa or Miami? In the case of today’s sandwich, the question isn’t so much who came up with the idea. (It was probably some hungry Glaswegian—or Wiganite, or Dundonian—who was served a pie so scalding hot that the only way to protect his or her fingers was to place it in a roll.) I’m more interested in who can claim its naming rights. In the Greater Manchester/Merseyside corridor they call it a “Wigan Kebab,” as evinced in the viral video below, in which a hapless vlogger consumes one, alongside local delicacies “smack barm pey wet” and “babby’s yed,” in a communion of carbohydrates.

The Glasgow Oyster is what Talia has dubbed an “orphan sandwich”—one that’s included on Wikipedia’s list but doesn’t have a page of its own. I have to admit, despite years living in Scotland, I never encountered a Glasgow Oyster, whether called that or some other alias. The given definition—“a scotch pie on a morning roll”—is slightly more specific than just a “pie on a roll,” but try telling that to a Wigan native.

In some form or another, the meat pie exists in cuisines across the globe, and it’s history goes back millennia. But no 21st century Glaswegian would mistake an Ancient Greek version for a Scotch Pie, which traditionally consisted of minced mutton, heavily spiced and baked in a hot-water pastry shell. There are, of course, countless other types of British meat pie—steak-and-ale, pork, rabbit, steak-and-kidney — to say nothing of pasties or bridies. The Glasgow Oyster, however, specifies that the pie be Scotch.

Other regional variations are less strict. Wigan, a former industrial hub roughly equidistant from Manchester and Liverpool, is famous for its love of pies. Fittingly, when Amelia Dimoldenberg sent out her twitter query, the most common response was the aforementioned “Wigan Kebab,” also known locally as a “slappy”, “jakey”, or “pie barm.” But from what I can gather, this particular version can accommodate any type of meat pie. In other words, a Glasgow Oyster could be considered a Wigan Kebab, but a Wigan Kebab can only be called a Glasgow Oyster if it’s using a Scotch Pie.

If I had encountered this sandwich during my time in Scotland, it would have likely been called something different again. In Fife, where I spent my college years, a pie on a roll is variously known as a “Ballingry Big Mac” or “Cowden Big Mac”, depending on the town. If you’re looking for a Glasgow Oyster in Dundee, you’ll need to ask for a “peh 'n a piece.” Elsewhere in Scotland it goes by Tartan Kebab, Govan Oyster, Scottish Kebab, Kirkie Oyster, roll and bridie, pie piece, pie butty, and Kirkaldy Salad. In Australia they call it a “piewich.”

Given my background and my ostensible authority in the sandwich arts (by dint of this newsletter, anyway) I felt mildly ashamed at my ignorance, and was determined to remedy it. As it turns out, in New York—a city of 20 million people, home to every cuisine you can imagine—I was unable to source a Scotch Pie, let alone a Glasgow Oyster. But I was determined to make do. If I couldn’t locate a proper Glasgow Oyster, surely I could approximate a Wigan Kebab, with its more permissive strictures.

So, earlier this week, I stopped at Myers of Keswick in Greenwich Village, my go-to shop for British specialties. While they didn’t have Scotch Pies, there were other offerings that seemed close enough, and I bought a selection: steak and ale, pork, and mutton curry. None of these was quite right—the pork pie had close to the right consistency, but the wrong protein; beef is often used in a modern Scotch Pie, but it should be minced, not cubed; and while mutton is the traditional meat, curry is a more recent addition.

To the uninitiated, this sandwich might seem like a carb-on-carb cholesterol bomb, and while far from healthy, it’s surely no more carb-laden than a chip butty, or worse for your heart than a doughnut sandwich. But while I can’t really vouch for the authenticity, I was happy with the result: all three of my home-made whatever-you-call-ems hit the spot. As for the surfeit of carbs—the hat-on-a-hat nature of the thing—I wasn’t bothered. After all, a club sandwich and a Big Mac both come with extra bread, and no one seems to worry about the consequences. And next month I’ll be piling stuffing onto my post-Thanksgiving pilgrim sandwich, and this isn’t really all that different.

Far from being redundant, the fresh-baked rolls slathered in butter helped insulate both hand and pie, while sopping up any stray grease or juices. The steak-and-ale version evokes a stew sandwich, not a bad thing on an October day. The curried mutton was delicious, something like a samosa sandwich. And the pork pie was certainly tasty, but to be honest, the roll didn’t serve much purpose given the pie’s temperature (warm) and consistency (solid).

So while I can’t truly enthuse about a proper Glasgow Oyster, I also can’t imagine a better treat to to eat during a chilly “Old Firm” match, or an early morning walk home from the pub. Whether you want to call it a Wigan Kebab or a pie barm or a roll ‘n peh or a Ballingry Big Mac, it earns its spot in the Wikipedia canon. It may not be “Scottish cuisine,” but would a sandwich by any other name taste as great? Or to quote Robert Burns, that great treasure of Scottish literature:

What though on hamely fare we dine,

Wear hoddin grey, an’ a that;

Gie fools their silks, and knaves their wine;

A Man’s a Man for a’ that:

For a’ that, and a’ that,

Their tinsel show, an’ a’ that;

The honest man, tho’ e’er sae poor,

Is king o’ men for a’ that,

Add a comment: