Notable Sandwiches #132: Pastrami

Hello, and welcome back to the Sword and the Sandwich! I’ve been struggling with a particularly pernicious case of writer’s block, for months now. Not being able to access the right words is tremendously upsetting—for me, a person to whom words have always come easily and in abundance, it’s rather like a sudden loss of limb—and the past few months have been a strange purgatory. I read several hundred books in an attempt to cram enough words into my head to have them spill over; had innumerable nervous breakdowns of varying severity; tried and failed to force my own hand to the page; and at last felt the words, slowly, start coming back to me, like the first snowmelt after a long and bitter freeze. For those of you who stuck around, I thank you infinitely for your patience. The current iteration of this newsletter will likely focus a bit less on politics, and perhaps be a bit less regular, but won’t disappear for months on end without warning—the best reassurance I can give in these benighted times.

At any rate, I thought it fitting that we return with a sandwich, the sandwich I’ve been neglecting for so long. (For months the very word “pastrami” made me twitch like a galvanized frog, reminding me of the meaty layers of responsibilities I was neglecting.) So here we are—back to Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, where it all began, plodding through the alphabet together.

In Riverdale, New York, the not-quite-suburb nestled in the Bronx where I went to high school, there is a deli called Liebman’s. For complicated reasons of Jewish law it’s on the edges of kosher respectability—while all the food is kosher-certified, it’s open on the Sabbath, and therefore part of the demimonde of kashrut, a place for those looser about the laws to go. That’s why I didn’t discover it until I was an adult, and can only mourn those lost years as anyone on the cusp of middle age does about misspent, youthful opportunities. Because that place has mustard sharper than a razor. It has chopped liver that’s creamy and gamey and perfectly sweetened with caramelized onion. The pickles you get gratis with every meal are the stuff briny dreams are made on.

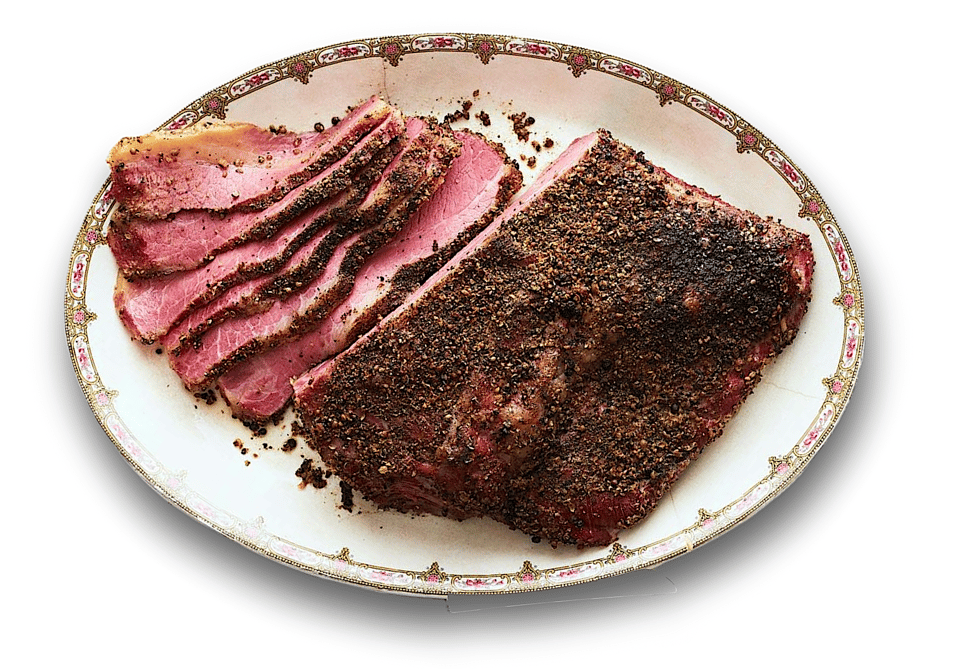

Most importantly, the pastrami sandwich at Liebman’s is everything a pastrami sandwich should be. Thick—almost preposterously so, red shreds sliding out of the bread in a sort of arrested avalanche—and smoky, the meat unctuously fatty, cut paper-thin, and served on caraway-studded white rye. It’s a sandwich to be lingered over. To be respected. It is not an hors d’oeuvre, or a frippery. It is not here to amuse your bouche. It is a feast in itself, and should be treated accordingly, granted time to be savored as the rare feat of care and craftsmanship that it is.

It has also come a very long way to get to Riverdale. Not the specific protein in any Liebman’s sandwich—the restaurant, founded in 1953, prides itself on house-cured pastrami—but pastrami itself. To get here from across the seas, it’s drifted away from ancient origins; shifted consonants and syllables; dropped an ending vowel and gained another; and arrived, not unscathed but improved. The story of pastrami is in its own way a story of the futility of borders to stop an idea; the way cultural intermingling is its own corning-spice of improvement; the way the most ceaseless and cruel of prejudice, oppression and hostility gave way, in the end, to the soft and yielding majesty of pastrami.

To start at the beginning:

The earliest traces of pastrami’s precursor—the cured-meat dish known as pastirma—can be found in the Caucuses in the fifth century AD. From there, reference, legend, and attestation dot the region with dried meat—known as pastramas in Greece, bastirma in Egypt, basdirma in Azerbaijan, pastarma govezhda in Bulgaria. Seriously, this dish has a lot of names.

There's also, unsurprisingly for an important foodstuff in this area of the world, a pretty serious feud around the origin of the dish. Etymologically, it probably comes from the Old Turkish word for "pressed," and the Turks have claimed primacy accordingly. Various Turkish sources also assert that the meat was pressed by the muscular thighs and posteriors of horsemen. The writer Ted Merwin, author of “Pastrami on Rye: An Overstuffed History of the Jewish Deli,” pictures Turkish nomads roaming through Central Asia with pastirma beneath their saddles, the meat “tenderized in the animal’s sweat.”

But Armenia isn't giving up its claim to pastirma so easily. No less august a body than the Armenian Prelacy, which governs the Armenian Orthodox Church, weighed in on the matter in 2016, reminding us: “the fact that the word is Turkish does not mean that the food is indeed Turkish.” An alternative theory to the horse-nomad origins of basturma posits that it evolved in Byzantium, and the Armenians adapted and dominated the industry, to the point where the surname Basturmajian—basturma-maker—was recorded by Ottoman tax collectors.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

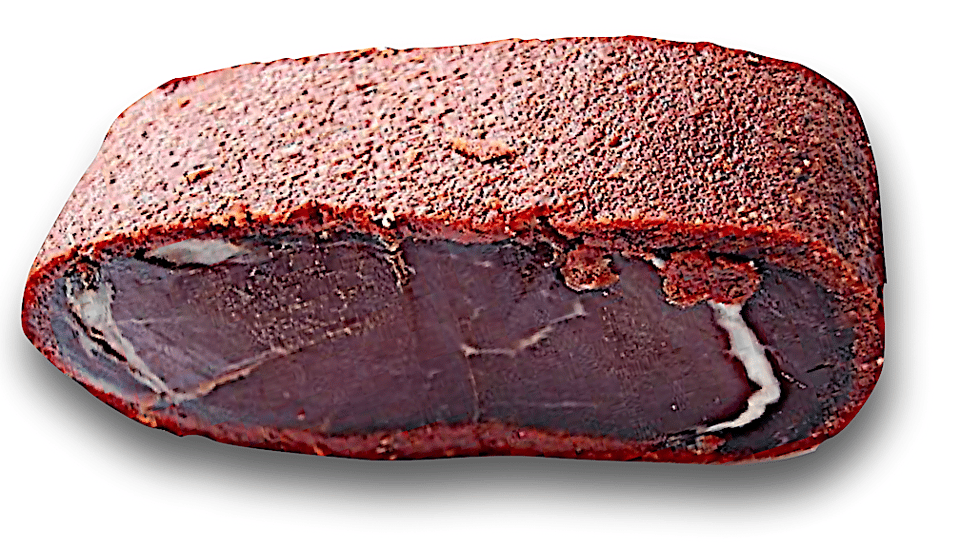

In Armenia, where basturma is still eaten as it’s been since roughly the fourth century, the dish is distinguished by its red coloring and the protective spice coating known as chaman; unlike with the unctuousness of pastrami, moisture is viewed as a sign of poor quality. According to David Underwood and Irinia Petrosian, authors of “Armenian Food: Fact, Fiction, and Folklore,” chaman is made by “mixing water with fenugreek, paprika, salt, ground black pepper, ground cumin, red pepper, allspice and garlic. Some basturma-makers will claim that their product is dried in clear, mountainous air. Don't believe it. Most homemade basturma is dried on clotheslines in someone's apartment balcony." You can still get pastirma all across Turkey, too, sliced thinly, served with shakshouka, or pide bread, or buried in a hot bourek. It coexists, in its ancient form, with the transposed-vowel evolution of pastrami that developed elsewhere, across the Black Sea in Europe.

From the Caucuses and the Middle East, pastirma hopped borders to Romania, evolving there from tough (horse-marinated?) beef to a spiced, pressed and dried staple—in Wallachia, the salted, smoked meat of a “young ram,” according to Le Monde. With smoking and salting rather than air-drying as its primary preservatives, pastramǎ (as it’s known in Romania) took on a certain delicacy, although it remained more jerky-like than its current American iteration. The Romanian pastramagiu (pastrama-maker and seller, and also, oddly, a synonym for “rogue” or “vagabond,”) purveyed cured meat that ranged from goose breast to ram’s flank to beef and pork, dried, and named for, its signature mix of spices.

It’s at this point in our story that the Jews enter stage left, and the journey from old-world, hard-smoked pastirma (with its many aliases) to the soft, yielding heaps in our contemporary pastrami sandwiches begins. Jews had lived in Romania, as across much of Eastern and Central Europe, for a millennium or more, but the latter half of the nineteenth century ushered in a series of dramatic shifts in the political landscape, as a rising tide of nationalist movements vied to carve their own independent states out of the flanks of empires. As with so much of European history, nearly every major upheaval was marked by the ancillary violence of the pogrom, particularly in 1821 and 1860. By the late nineteenth century, Moldavia and Wallachia had united into the Kingdom of Romania, transforming from disparate vassal states of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires into an independent kingdom in 1881.

Naturally, one of the first political acts of the new kingdom was to decree official policies of antisemitism, preventing Jews from settling in the countryside while also declaring urban Jews to be vagrants; Jews were systemically denied emancipation and civil rights. Even as persecution rose, Jewish theater, literature, and internally-focused political movements such as socialism and Zionism thrived. This mix of oppression and opportunity, vivid intellectual life and poverty, is perhaps most famously rendered in the Yiddish classic song “Roumania Roumania,” a fiddle-dance bop composed in 1925 by Aaron Lebedeff—and which name-checks pastrami in the first verse:

Oh! Rumania, Rumania, Rumania …

Once there was a land, sweet and lovely.

Oh! Rumania, Rumania, Rumania …

Once there was a land, sweet and fine.

To live there is a pleasure;

What your heart desires you can get;

A little mamaliga, a little pastrami, a little karnatzl,

And a glass of wine, aha … !

By the time Lebedeff wrote his ode, Romanian Jews were increasingly subject to pogroms, enmeshed in the precarity of interwar Europe, soon to become a closing net around them. But between 1878 and 1918, some 70,000 Jews had emigrated from Romania to America. They brought their pastrami along. While Romanian pastramă could be made with fowl or mutton, in America, beef—specifically beef navel—was widely and cheaply available; could be made kosher, unlike pork; and proved adaptable to all sorts of imported curing methods. Thus beef quickly became the ubiquitous vehicle for pastrami and its crusty spices.

Here’s where my nominal and self-appointed job as a sandwich historian gets extremely frustrating. In trying to identify the specific transition point between the smoke-dried jerky of the Old World and the steamed, luscious pliability of New World pastrami—which is brined, smoked, boiled, then steamed before serving—I was thoroughly flummoxed. Dueling New York immigrants—the family of deli-man Sussman Volk, and the family behind Katz’s Delicatessen—claim to have sold the first pastrami sandwiches in America in 1887 and 1888, respectively. What they allegedly sold, though, was a soft meat in a readymade sandwich, far more supple than the jerky-like wares hawked by the pastramagius of Bucharest. What I cannot find, specifically and despite an exhaustive amount of research, is why, when, or how this transition came about.

I can tell you a few things: salt brine is crucial to the preparation of kosher meat, in order to obey the Biblical injunction against eating blood; it’s an ancient and relatively simple system that is integral to Jewish meat-eating of any kind. Another fact: industrial-strength steam injectors were invented in the mid-nineteenth century in France, and have subsequently come to play a large role in pastrami-making. Steam tables, of the type still used to keep deli food warm in Liebman’s (and everywhere caterers flourish), were patented by one George W. Kelley in Norfolk, Virginia in 1897. Steam cooking itself is thousands of years old, from plaited-bamboo steamers gently cooking dumplings over a fire in Japan to corn-husk-wrapped tamales, which originated between 8000 and 5000 BC. And the pastrami that was sold in the US by Romanian Jews always had a salty softening before being sold: according to an exhaustive debunking of the (insane and wrong) theory that pastrami originated in Texas over at Serious Eats, pastrami undoubtedly appeared across the US in the late 1890s, and was a brined or pickled product from the get-go—unlike its hard-dried European counterpart.

One reason, perhaps, that it’s hard to find information about the transformation of pastrami from rock-solid to delightfully pliant is that the damn word, particularly when transliterated from Yiddish, can be spelled any of a dozen ways. Pastramă (if you want to go Romanian); pastrame, closer to the Yiddish pronunciation; pastrome; pastramy; pastromer; pastroma; and so on. (As to how “pastrami” became the agreed-upon spelling: the “-mi” ending is reminiscent of “salami,” which took on a metonymic quality for lots of other kinds of cured meats with the flood of Italian immigration to the US in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Or so food historians theorize.)

Other facts to affix on our timeline: Delicatessen meat, often with the softer and more yielding texture typical of German charcuterie—think bologna and ham, not hard salami—was a legitimate American national craze in the latter half of the nineteenth century. By the 1920s, newspaper articles (and ripostes, and hot takes) bemoaned the lazy “delicatessen wife” whose domestic labors consisted of merely picking up and then unwrapping some pastrami, pickles and rye, instead of slaughtering, smoking, steaming, baking, and generally wracking her body to create each meal and thus demonstrating her devotion to her domestic role. Plus ça change, plus la meme chose—anything will cause the press to bitch about women—but also, this newsletter is firmly on team Deli Wife.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, other immigrant groups had begun to muscle in on the Germans’ delicatessen monopoly, including Romanian Jews. And while the hard-cured meats of the salumeria are easier to store for long and thrifty periods, soft slices of liverwurst and pastrami are a far better quick lunch or dinner, ideal for the fin-de-siecle factory worker or proto-flapper wife with better things to do than spend all day bent over a stove.

All of this is suggestive, but fundamentally, it’s conjecture. Without being able to dig up reliable primary sources from under the black crust of a century, it’s ultimately unclear why traversing the Atlantic Ocean caused a hard-smoked meat to transform into soft smoked and steamed meat, why the Jews did this, and through what agency this indulgence arrived at our tables.

I’m complaining, here, not about the process itself, but about the paucity of reliable information around it—an unfortunately common stumbling block in sandwich research, as culinary history in general is prone to legend and lacuna alike. This is a problem of historiography: the domestic and ubiquitous is rarely documented with as much care as conflicts and kings, though to me it is and always has been of equal importance.

I think we should know everything about meat and bread, at least as much as we do about blood and conquest. I hate not having the answer myself, and still less, after all this time, not being able to provide you with one.

Perhaps it was the sea itself, as they crossed it from Romania with hope and terror, that gave these immigrant deli-mongers the idea to brine and steam pastrami to tenderness. That is as good a theory as any other factless postulation.

If you look closely enough at the history of pastrami—and the utter futility of national borders in the face of its smoke and salt and spice—it’s more fitting than most. Moreover, if the origins of pastirma are caught up in the saddles of horse nomads, it’s appropriate to affix pastrami in the modern iteration of nomadism—the great movement of immigration, the sea of people washing from shore to shore, fleeing blood through salt water, in the hope of good, and gold, and in the process bringing old provender to a new land.

-

Hi Tali Just t‘other day I was wondering about the absence of The S&S - and Viola as the dyslexic Frrnxhman said. I loved this one & a true deeply goyish southerner Matt Neal, son if two outstanding southern chef/restauranteurs, started zahle in the wall Neal‘s Deli about 15 years ago & made what I swear it’s some of the best pastrami I’ve ever eaten - and the sandwiches are not the gluttonous size we’ve perversely come to expect. He also made a very respectable pickled green tomato & before selling the place had begun to take on the persona of a deli man complete with stained white apron & middle aged gut…. It seems you’ve broken thru writers block with this one! Mazel Tov Cousin Bleh Ps my friend Bernie Most, in his 80s s now sings with the local Magnolia Klezmer band, a really spot on version of „the pastrami song“ you cite.

-

Welcome back!! Loved this. Think I'm going to add some to our grocery order this week!

-

Excellent story! Glad to see that the words are back.

-

Glad you're back! Enjoyed this very much-- very informative. As a child I always confused pastrami and corned beef because I didn't like either one very much--too "weird" for me (and I grew up in NY!). Which is stupid, because I loved bologna which truly IS a weird meat product. At any rate, I've found my way to both types of sandwich meats as an adult (hot pastrami on rye and the reuben) but don't eat either one very often. Have you talked about pastrami vs corned beef in this series? Very different origins?

-

There's some pastramic lore being left out here, but specifically about the horse-cooked beef of the Asian steppe: it's not the animal's sweat that's doing the work. It's the repeated impact of the saddle which cooks the meat. There's a modern-day meme about "slap-cooking" demonstrating how you can impart just enough kinetic energy which is converted to sufficient heat by repeatedly striking just about anything. But about pastrami itself, I believe the Armenians, because basturma is clearly part of the larger pickling/drying traditions of Eastern Europe like corned beef or Montreal's viande fumee.

-

Wonderful! Great to read your writing again.

-

Glad your words have come back. And there couldn't be a better subject for them to land on. Thanks for your diligence.

-

Welcome back!

-

Glad to see you Talia!

-

What a glorious return! I was so happy to see this in my inbox today!

-

This level of sandwich scholarship has yet to be beaten. Thank you for sharing with us!

-

I'm so glad your words have come back to give us this delicious piece of writing. I wish I lived in a place where Good corned beef and pastrami were available as you've made me very hungry for this king of sandwiches.

-

Welcome back. Now I know what I've been missing.

Add a comment: