Notable Sandwiches #130: Panini

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where my intrepid editor David Swanson and I take our seats at the big strange table that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, and sample a dish each week, in alphabetical order. This week: the panini.

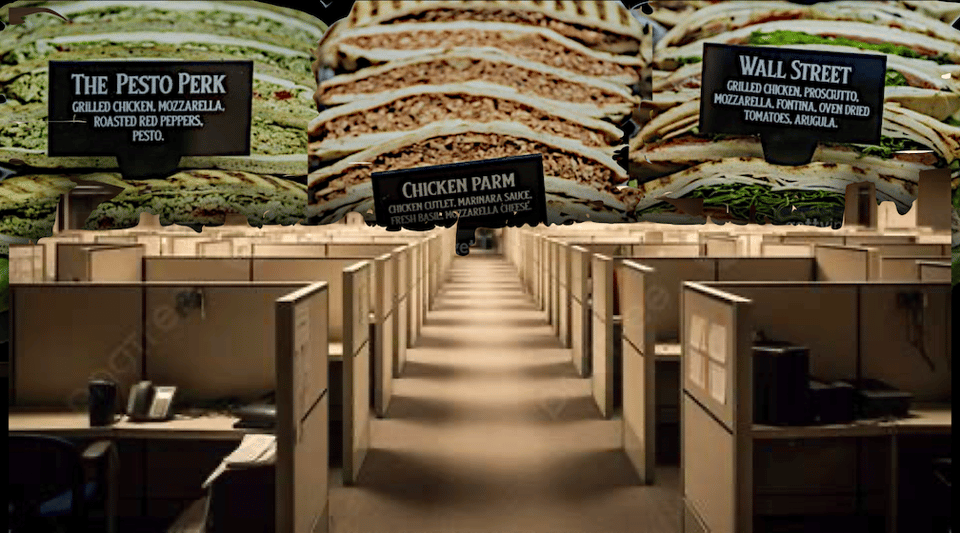

When I think about paninis, my first thought is Sad Desk Sandwiches.

Back in the days when I actually went into an office to work, and had health insurance paid for by an employer, and had other people telling me what to do, and had a rough shape to my life, I spent a lot of lunch hours poking around various delis. What I recall most vividly is that they all had rows of paninis, and they were all the same. Eggplant parmesan, chicken pesto, vegetable-and-mozzarella, on sad pallid bread, packaged identically. I never solved the mystery of what corporate elf managed to stock every bodega in a mile radius with identical sandwiches, but they were so uninspiring that, frankly, I found the prospect of this column profoundly unappetizing, even at a distance of the seven years since my office days.

(God I miss going to an office! I miss everything but the sad paninis. Even those, I think, I would come to accept, if not embrace.)

So I found myself writer’s-blocked by a panini. What weakness! To be trammeled by something so helplessly ordinary. So ubiquitous. Rarely a first choice, but often a solid one, in the American context: hot off the press, usually with a fine runnel of melty cheese, a good crust, a sensible protein or two. Perhaps nothing to make a poet’s toes curl, nothing to make the words sing off the page, but a reliable, filling option, and thus worthy of a certain amount of modest celebration. A basic bitch of a sandwich, but a basic bitch can be a trustworthy friend, and not to be scorned in the least.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

Then I remembered what it is we do here. So I decided to look closer. The point, after all, is to unearth unexpected truths in things we overlook, even those things I was so powerfully inclined to dismiss. I remembered the two truths of research: look to primary sources, and follow them wherever they take you, however unexpected that may be.

So: where did the panini come from, and when?

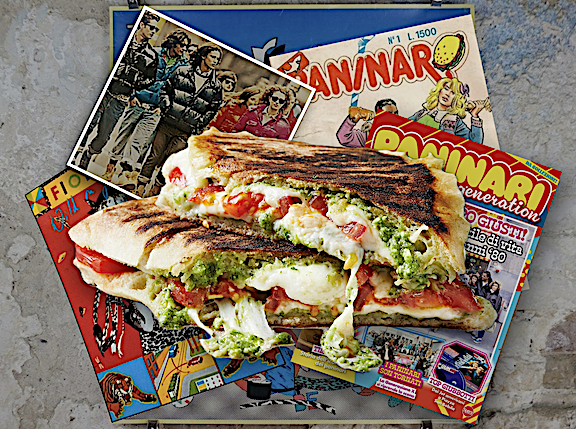

Well—Italy, obviously, where it’s referred to by the singular panino. A panino isn’t necessarily the pressed item Americans sell wan and insipid or fresh and hot; it just means a small sandwich. A panino imbottito, a ciabatta or rustic loaf halved, stuffed, pressed, and lightly grilled, meets the brief for what we think of as a panini.

Panini have been around for awhile—electric grills first surfaced in the 1930s, with dueling claims of invention coming out of Milan and Lombardy—but it wasn’t until the 1980s that the fad took off in Italy, with upscale paninotecas cropping up in the trendiest neighborhoods (and their fast-food analogues lining less distinguished boulevards, offering a hot meal on the go).

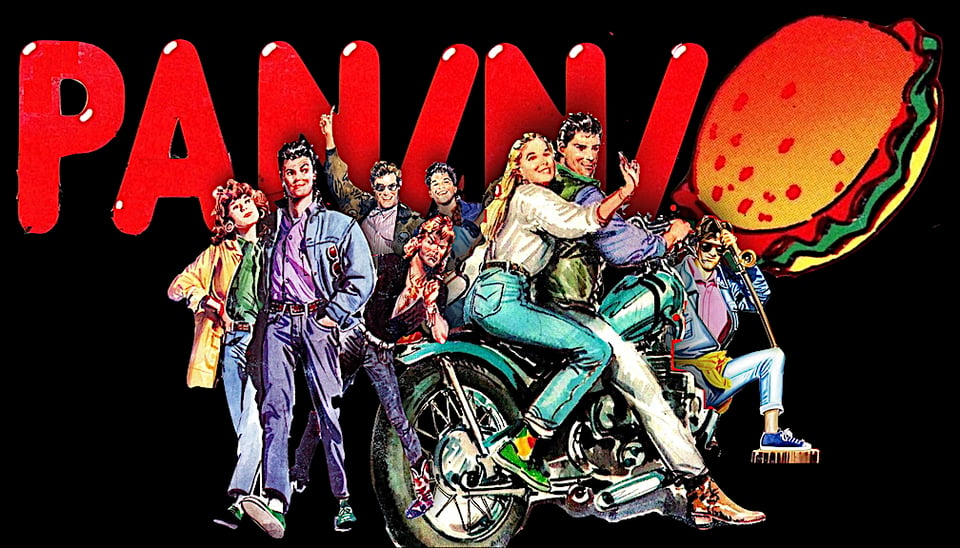

They also spawned perhaps the only youth subculture named after a sandwich. At least, the only one I’ve heard of. Italy in the ‘80s witnessed the tail end of the long, exhausting, and terrible political struggles known as the Years of Lead, which saw neofascists and radical leftists, many of whom were students, committing bombings, kidnappings and brutal assassinations against their opponents. The paninari—young guys who hung out at trendy panini bars—wanted out of all of it. The culture first began with young, fashionable fascists, but as it grew into a mass movement, it became more or less apolitical—at least in the sense of the brutal, blood-in-the-streets politics that had defined Italy for decades.

By the time the wave swept the nation in the mid-80s, the paninari wanted to look cool, have money, and hang out. They wanted to surf in Malibu and ski in Gstaad. They didn’t want to hang out at their parents’ kitchen tables eating elaborate, homecooked multicourse meals. In Italy, eating panini and hamburgers was a form of rebellion. Forget Molotov cocktails; they wanted to drink real cocktails, and espresso, eat trendy sandwiches, wear designer clothes, and listen to British synth-pop. They wore hair gel, Argyle socks, Nike shoes, puffer jackets.

As the Guardian wrote in a recent article about the group’s online resurgence, “the Paninari presented themselves as the spirit of the time, a subculture of the winners, the cool guys who made money—or were good at giving the impression they did. At first, it was a rich boy’s club—the scene started in Milan’s wealthy city centre, around the snack bar Il Panino, hence the name—but eventually middle-class kids joined, even if it was beyond their budget.”

They were preppies, more or less, with the attendant conservatism therein, but were more interested in Gucci than guerilla warfare of any sort. They were the cutting edge of hyper-materialistic cool, for a while, turning away from armed struggle in favor of consumption—of paninis, of fashion, of the right look, and the right sound.

This was a match made in heaven for the decadence of the ‘90s, particularly in New York, where Wall Street and Fashion Week collide. Paninis are mentioned in English from the ‘50s onward, mostly as descriptions of little stuffed Italian rolls; by the ‘90s, like good suits, the sandwiches were pressed, and fashionable. The haut ton of Los Angeles and New York alike nibbled on the brand-new import, in the kind of circles where what you wear and what you eat is who you are.

“Light, flavorful and, yes, oh-so-trendy, panini (like coffee bars) have leap-frogged across the country,” wrote Walter Nicholls in the Washington Post, in 1995. “From Seattle to Chicago to Dallas, hot pressed sandwiches, made with focaccia or rustic bread, striped with grill marks, are a have-to-have with that latte.”

But nothing trendy can stay trendy forever. By the aughts, paninis had begun to slide from the modish to the passé, reaching its nadir at some imperceptible point. By the time I was nosing from deli to deli with my few bucks for lunch in the late twenty-teens, panini were Sad Desk Sandwiches. Nothing gold, even golden-crisp, can stay.

But of all the sandwiches in the world, few can lay claim to have given name and embodiment to a moment of hedonism in a culture overladen with violent ideals. Fewer can lay claim to a moment of white-hot international trendiness, however brief.

The history of the panini is as ever a lesson the Notable Sandwiches series has pressed into me and left grill marks: nothing is too ordinary to overlook. Peel back the layers, look a little harder, and there’s inevitably more to see than you think. The grain of the bread, the politics of the moment, the weight of the press, the yielding of the crust—all of these are important, worth examining. The more curious you are about anything and everything, the more rewarding it is. Satisfactory, even, like the last bite of a greasy-hot lunchtime sandwich.

-

Altogether now: 🎶 “Panin-AR-o! Panin-AR-o, oh-OHHH-oh!” 🎶

Add a comment: