Notable Sandwiches #128: The Princess and the Pambazo

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the movable-feast where my editor David Swanson and I pull up a chair at the strange table that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches and invite you to dig in. This week, David tells the story of Empress Carlota of Mexico, and the Mexican staple she inspired: the pambazo.

When it comes to researching sandwiches for this project, Talia and I have approached our task with a rigor befitting its import: interviewing academics, translating primary texts, experimenting in the kitchen. But with everything going to hell all around us, I figured we could use a distraction, and what’s a better distraction than a good story—even if its provenance is dubious, and it may be more legend than accurate culinary history with regards to the source of a beloved Mexican staple? And so I give you the tale of the Princess and the Pambazo.

Once upon a time, in the snow-white Miramare Castle on the Gulf of Trieste, Princess Charlotte of Belgium became Empress Carlota of Mexico. Up until that point, she’d lived a fairly standard, sheltered existence for a European royal—most of whom she was related to anyway. It was a small world she’d grown up in. At the age of seventeen, seven years before being crowned Empress, Charlotte had married her Prince Charming, a long-faced Habsburg who would henceforth be known as Emperor Maximilian I. At their new home in the New World—Chapultepec Castle, in Mexico City—she sought to recreate the splendor of old Europe: formal balls, ornate gowns, gourmet feasts. To help with the last of these, the imperial couple had brought along a loyal Hungarian chef named Josef Tüdös. Maximilian’s brother Franz Josef was the emperor of Austria-Hungary—and he wanted a taste of home.

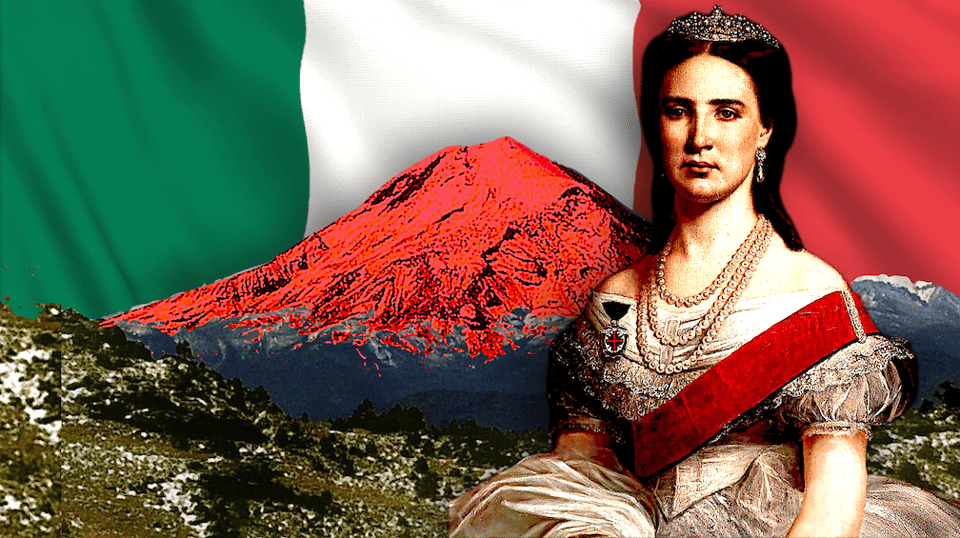

It was on May 31, 1864, during the couple’s journey from Mexico City to Veracruz, that Empress Carlota first laid eyes on Citlaltépetl, a volcano that loomed over the Xalapa countryside. Upon their arrival, she and her husband were rapturously welcomed by the local native population, who regaled them with gifts and cries of “Viva el emperador!” The empress was enchanted, by both her new subjects, and by the view of the majestic volcano. To celebrate the reception, Tüdös decided to prepare a dish which evoked the vista that the young empress found so bewitching. Tüdös’s creation consisted of a soft, white pan basso roll, annointed with a lava-like, paprika-rich sauce, and then fried on the griddle to give the bread a crispy exterior. This shell was then stuffed with chorizo, potatoes, queso fresco, crema, salsa, lettuce, and avocado. The fried potatoes and paprika were emblematic of the Imperial couple’s Belgian and Hungarian heritage. The green avocado and lettuce, the white queso and crema, and fiery red crust and salsa bore the colors of the Mexican flag. Tüdös dubbed this creation "Capricho de la Emperatriz": The Empress's Caprice. The rest of us would come to call it pambazo.

That’s the legend, anyway, and it’s a decent one as far as sandwich origins go. 160 years later, the pambazo is a Mexican staple, and the story of Carlota and the sandwich has stuck, apocryphal though it almost certainly is. Regular readers of this column will know how tricky it can be tracking these histories. (Just look at the Earl of Sandwich. Does anyone really believe he was the first person in history to consume his namesake invention?) Through intrepid research, Talia and I have managed to tease out the fact from the fiction regarding several of the sandwiches so far—the leberkäse memorably gave us the Ghost Butcher of Bavaria—and the truth of the pambazo is likely far more prosaic than the above scene suggests. But what fun is that?

For the record, more traditional scholars might tell you that the sandwich evolved naturally, that it started as a fairly basic sandwich and was embellished and improved over time. The name comes from “pan basso,” a soft roll liable to disintegrate under the weight of the chorizo and potato—but when it’s dipped in the piquant sauce made from guajillo peppers, and then fried, gains a proper crust, able to withstand the dense moisture within. This crust is the pambazo’s distinguishing feature. Other sandwiches, like the Italian Beef or the French Dip, also infuse the bread with a sauce or gravy of some kind, albeit after the sandwich is cooked. The Monte Cristo—and French Toast in general—is a closer analogue; there the bread is dredged in egg before being fried. But the particulars of the pambazo are unique.

Today, it comes in a number of varieties, the Mexico City version being the standard, and the one you’ll likely see sold here in the United States. Other regional pambazos might include beans, onions, beef, chicken, shredded ham, turkey, or fish. Alas, I have yet to sample a pambazo, which is a shame, because it sounds pretty spectacular: the heft and savor of the chorizo and potatoes, the heat of the guajillo, the cool, freshness of the vegetables, the bright salsa, the creaminess of the cheese. These are the kinds of components that, when balanced, make for a near-perfect sandwich. And I, for one, am perfectly comfortable giving at least some of the credit to Empress Carlota and loyal Tüdös.

The truth is, in researching the pambazo, I was struck by the fact that Carlota warranted further consideration, if not celebration. The fact that I find her fascinating shouldn’t be taken for any kind of endorsement of colonialism, which clings to her story like a trail of salsa. Carlota was the sister of Belgium’s King Leopold II, founder of the gruesome Congo Free State. She was also granddaughter of the deposed King Louis Phillipe of France, and her first cousins included Britain’s Queen Victoria. Her husband, meanwhile, had been placed on the Mexican Imperial throne to serve as a figurehead for French colonialist interests. To their credit, both emperor and empress prioritised the needs of their indigenous subjects over those of the European settlers who had dominated Mexico for centuries. But Carlota’s advocacy for her new home would ultimately come at a cost to her sanity.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

Altogether, Carlota lasted a mere three years in Mexico before civil unrest compelled her return to Europe to lobby France’s Emperor Napoleon III, Pope Pius IX, and Maximilian’s brother Emperor Franz Josef, for military and monetary assistance. It did not go well, and Carlota’s desperation and disappointment led to a series of the mental breaks that were to plague the empress for the rest of her life. She became so convinced someone at the Vatican was trying to poison her that she convinced the Pope Pius to let her share his supper and sleep in his quarters. Over the years, she suffered flights of fanciful delusion, phases of acute nymphomania, and fits of manic rage. Every spring she would ask when she and Maximilien would be returning to Mexico. The truth was nearly more than she could bear.

As for Tüdös, he stayed devoted to the last. In fact, he was with Maximilien on June 19, 1867, when the emperor was executed by the leaders of the nascent Mexican Republic. M.M. McAllen recounted the scene in Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico:

“The emperor, who looked somewhat pale, held his head high. ‘He already seemed to belong to another world. Beside him trotted his little Hungarian cook like a faithful dog hanging on his last words,’ said Magnus. Maximilian turned to Tüdös, who had lived in denial that his master would be put to death. ‘Now do you believe that they are going to shoot me?’ he asked. ‘To die is not so difficult as you think.’ He wiped his brow with his handkerchief and handed it to Tüdös along with his sombrero, and asked him, in Hungarian, to take them to his mother, the archduchess. He kissed the crucifix and returned it to the padre.”

This moment, which sent shockwaves through global politics, was famously captured in a painting by Edouard Manet. You can almost picture poor Tüdös mourning his employer just out of the frame.

It would be years before Carlota learned the fate of her husband, so concerned was her family about the impact the news might have on her fragile condition. Over the next several decades, she resided at Bouchout Castle outside Brussels, mostly cloistered from the outside world like an imperial Mrs. Havisham. The New York Times reported on her near-death state repeatedly over the years, but her health consistently rallied. By the eve of World War I—which was precipitated by the death of her nephew, Archduke Franz Ferdinand—Carlota had been living in Bouchout for almost half a century. Though the countryside around the castle was gouged with trenches and strewn with spent shells, Carlota remained safe. The Belgian soldiers would never harm their princess, while the German soldiers were instructed to let the castle bearing the Austro-Hungarian flag go unscathed. She would live until the age of 86, dying in 1927, having outlived her husband by sixty years.

In death Carlota is recognized as the first woman to govern a nation in the New World. Maximilian spent much of his time away from the imperial court in Mexico City, and it was left to his wife, as regent, to keep the country running. Overall, she sounds like a high-strung, somewhat difficult, supremely capable woman who was laid low by an unquiet mind. Her legacy, to be sure, is mixed. She’s been the subject of countless novels, plays, telenovelas, and movies—including a 1937 melodrama starring a Bette Davis.

But the pambazo may be Carlota’s greatest legacy, a mix of the flavors and ingredients of the old world and the new, and a symbol of the adopted nation she called her own: today, the sandwich is eaten on Mexican national holidays. The legend of its invention may be nonsense—I certainly embellished it here for my own purposes; that early appearance of the paprika-rich sauce is a detail of my own invention, as is the notion that the colors were chosen to evoke the Mexican flag. But that’s the thing about legends: they don’t have to be factual to feel true. And even when there’s no happily ever after, we can all use a good story.

-

That looks delicious! Love your sandwich adventures.

Add a comment: