Notable Sandwiches #126: Num Pang

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where I, your host, along with my editor David, lay out the multifarious and strange feast that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week, a Cambodian favorite: the num pang.

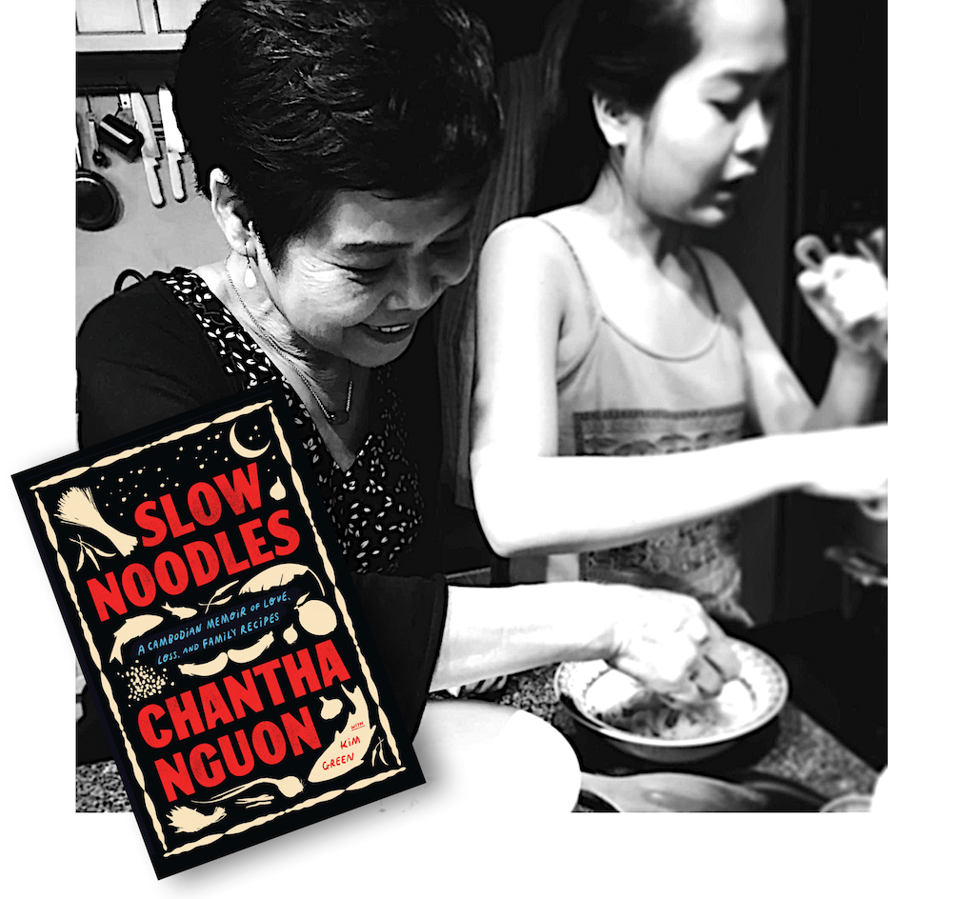

“Cambodia has a rich past, a mosaic of flavors from near and far,” Chantha Nguon writes in her book Slow Noodles: A Cambodian Memoir of Love, Loss, and Family Recipes. “South Indian traders gave us Buddhism, an alphabet, and spicy curries; China brought us rice noodles and astrology; and French colonizers passed on a love of strong coffee, pâté, flan, and a light, crusty baguette. We lifted the best tastes from everywhere and added our own."

The num pang sandwich—close cousin to the banh mi and khao jee pâté, the Vietnamese and Laotian variations, respectively, on the French jambon-beurre—emerged from this complicated tradition. It’s a relic, as Nguon notes, of “empires past, which contributed ingredients” to the complicated stew of Cambodian cuisine. Like its kindred, it’s composed of a well-buttered baguette—softer, crispier, and lighter than the French version—usually stuffed with pâté de foie, pickled carrot, and daikon radishes. French Indochina, which was composed of modern-day Cambodia, Laos, parts of Vietnam and coastal China, held Nguon’s homeland as a protectorate from 1887 to 1945. With a brief interregnum in which Cambodia was subject to a bellicose, expansionist Japanese Empire, and a subsequent return to French rule, the country finally won its independence in 1953.

(The life of Cambodia’s king, Norodom Sihanouk, who became official head of state in 1953, would make for several novels in and of itself; he abdicated the throne in 1955 to become prime minister; was overthrown by a right-wing military coup; backed the brutal Khmer Rouge during the ensuing civil war, then was placed under house arrest by them; went into exile; was reinstated on the throne; abdicated again; and also found the time to make more than twenty movies, some of which he also starred in, with titles like The Phantom of My Beloved Wife, Khmer Robin Hood, and Peasants in Distress. He died in 2012 at 89.)

But food—like trauma—sticks around. Even when ushered in by violence, shifts in cuisine slip across borders, from the colonial overclass to the masses, transformed and retained through subsequent decades. Cambodia emerged from its status as a French protectorate with two bowls of rice in its hands and a baguette tucked under one arm. Rice, which served as legal tender in the ancient days of the Khmer Empire, survives as the uncontested bedrock of Cambodian cuisine. According to Miller Refereed—a specialty magazine for millers and grain technologists—more than half the cultivated land in Cambodia is reserved for rice production; by comparison, “almost 70% of the wheat flour consumption is met by the industrial production of two local mills in Phnom Penh,” with the remaining 30% imported from Vietnam. So the num pang is a brief detour on a long, complex, rice-studded journey, an inherited and retained dish that serves as a lagniappe rather than a staple.

Evidence of bread’s late entree into Cambodian cuisine is stamped on the language. The word for bread in the Khmer language, num pang, is a direct French derivation: num means “cake,” while pang is a transliteration of pain, the French word for bread. Still, the num pang has a compelling number of variations: in addition to the standard pâté style, you can get a num pang with lemongrass beef skewers, coconut shrimp, pork meatballs, tomato-simmered fish, pork belly, sardines, and oxtail, among many others. In her memoir, Nguon calls French-Cambodian dishes a “tangled taste of bittersweet … evoking the unhappy, complicated marriage of colonizer and colonized.”

This isn’t a column about imperial nostalgia, or contrasting one violent regime with another, or debating the merits of life under a protectorate versus freedom (still, freedom is obviously preferable, and colonialism is bad, and the French have so much overseas territory to this day and no one talks about it and it’s weird). This is an essay about a sandwich, although, as readers of this column may have noted by now, a sandwich is rarely just a sandwich—particularly in this case, when so much (violence, empire, hunger, satiation) is contained within its crisp exterior. What is safe to say, I think, is that food—by virtue of both its ubiquity and its intimacy, the way it’s passed from generation to generation in a family, and its significance as a social signifier—rarely stays static in meaning.

This is vividly evident in Nguon’s memoir, which was published in 2024, and is achingly sad, harrowing, and delicious by turns. In her earliest years she lived a relatively pampered life as the daughter of a Peugeot mechanic and a housewife in Battambang, attending a French-language school. Accordingly, the first chapter is entitled “Soft Like Pâté de Foie.” But life in Cambodia’s most tumultuous decades would, inexorably, harden her. At the age of nine, she was faced with the terror of her first brutal regime, one of several she would experience.

Fleeing from mob violence against Cambodians of Vietnamese descent under the right-wing government of Lon Nol in 1970, Nguon was sent to Saigon with two siblings; her mother stayed behind in order to earn and send money to support her children. “Here is what Mae [Nguon’s mother] knew: Vietnamese businesses were in ruins, families turned out of their homes. The corpses of murdered Vietnamese men floated down the Mekong River. Mae was Vietnamese. And her children were fatherless and half-Vietnamese,” Nguon writes. “My mother planned to join us as soon as she could earn enough to make us safe. We didn’t yet grasp that safety was a ghost, a shadow, a child’s lullaby. Or that leaving Cambodia would soon become nearly impossible.”

An escape across the border in the midst of the Vietnam War—in which soldiers’ caskets and the crack of gunfire were routine sights and sounds—was preferable to remaining in Cambodia, as it happened, though her sister was injured by a stray bullet during the Fall of Saigon in 1975. Nguon’s mother and brother, who had remained behind, were forced from their homes by the Khmer Rouge that same year. Her mother escaped to Vietnam, rejoining her children; her brother was one of the millions who perished under Pol Pot’s regime. Another brother died in Saigon, then her sister, then her mother, until at last Nguon was alone.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

The memoir is full of almost incomprehensible suffering and loss: fleeing postwar Saigon to a Cambodia still ravaged by civil war and a shattering US-led carpet-bombing campaign; working as a brothel cook on the Thai border; escaping by boat from Cambodia; nearly ten years in a refugee camp in Thailand; repatriation to Cambodia in the ‘90s; nearly dying of malaria in the jungles of Ratanakiri; and becoming a healthcare coordinator for Médecins Sans Frontières in Stung Treng. “I had faced my worst fears and tasted hope and despair enough for two lifetimes,” she writes. “I had feasted on pâté de foie and roasted jungle snake, and everything in between.”

Pâté de foie is the taste of her girlhood, and it weaves its way throughout the book—as a recollection of decadence lost; as a self-rebuke during moments of want, of having once lived a life of luxury; of the treasured memory of a beloved mother, loved too briefly and then gone. The book begins and ends with it, starting with a scene from childhood:

The memory of hunger is a curse that never leaves you. The memory of happiness also lingers—I will never forget its flavors and aromas. It smelled like cloves, cracked pepper, and pâté de foie. On special occasions, Mae spent hours cranking chicken liver, pork, and pork fat through a grinder until it was velvety smooth. She stirred in garlic and cloves, wrapped the ground meat in a translucently thin slice of pork belly fat, and steamed the mixture in a square tin that had once held French cookies. She carved the vegetables into roses to decorate the plate, and we ate the pâté like a sandwich, with a Khmer baguette, and pickled carrots and daikon. I loved the holiday feeling that filled the kitchen whenever she made her pâté de foie.

Decades later, she “resurrects” the pâté de foie for a regional MSF representative. “The steaming aroma of fatty pork and liver, steaming over a charcoal fire, nearly brought me to tears.” She worked for MSF, rising out of poverty, and eventually opened a women’s center in Stung Treng, teaching weaving and providing healthcare. She had children, and raised them.

“A refugee must learn to be anything people want her to be at any given moment,” she writes in the book’s final chapter. “But behind the masks, I am only myself—a mosaic of flavors from near and far. Pâté de foie. Grilled prahok. Poor Grandmother’s pickles. Land-mine chicken. My mother’s slow banh canh and instant Mama-brand noodles … I am a translator—part wordsmith, part diplomat. Rich and poor. The past and the future. My mother and my children.”

The last recipe Nguon offers is for her and her mother’s jointly conceived pâté de foie, the sine qua non of the num pang. It has chicken liver, cognac, peppercorn. The last words in the book are “grind more black pepper over pâté and serve with a Khmer baguette.”

How do you rebuild a shattered country? How do you push on past loss, past borders, past war after war, and remake a life? How do you survive the unimaginable, and what do you bring with you? These are some of the questions that haunt Nguon’s memoir, and she offers only her own life as an answer. But what a life it has been! Rice is what you eat when you have everything and when you have nothing, she says. But in her heart a corner is reserved for the softness always, for the luxuriant pliancy of pâté on bread. And from that mix of strength and softness arises a remarkable tale of survival—and the story of the last half-century of a country that has suffered much, and emerged with more to tell.

Add a comment: