Notable Sandwiches #123: The Mother-in-law

By David Swanson

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where I, alongside my intrepid editor David Swanson, go down to the crossroads that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches. This week, David takes on a Chicago oddity: the mother-in-law. — Talia

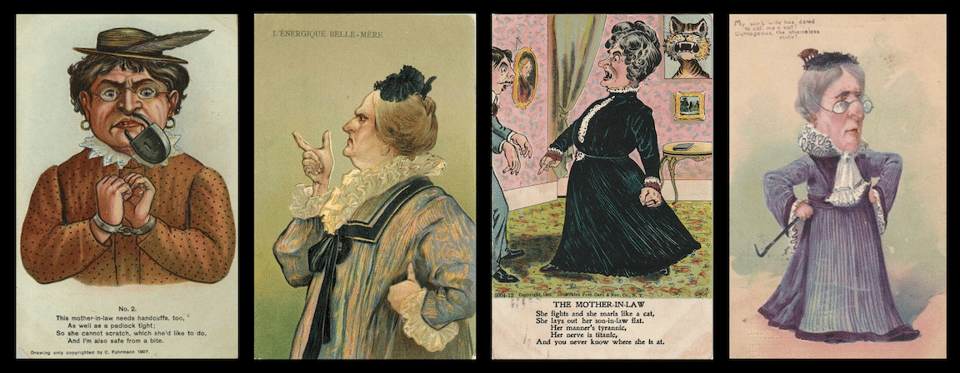

The poor, beleaguered mother-in-law—that age-old menace to domestic tranquility—has been a punchline for as long as we’ve been telling jokes. “A man will never be happy while his mother-in-law lives,” wrote the satirist Juvenal in 1st Century Rome. “She teaches her daughter evil habits.” “My mother-in-law said, ‘One day I will dance on your grave,’” said comedian Les Dawson in the 20th century Britain. “‘I said, ‘I hope you do. I will be buried at sea.” According to the Scottish anthropologist Sir James Frazer, writing in 1890’s The Golden Bough, “the awe and dread with which the untutored savage contemplates his mother-in-law are amongst the most familiar facts of anthropology.” (Perhaps this reflects an incipient dread of matriarchy, or the vulnerability of older women to attacks from across all social strata; then again, maybe we’re just not privy to some truly nightmarish family dinners in the deep jungle.)

Why, then, would anyone name a meal after this reviled figure? In the case of this week’s sandwich, the name seems to serve as a warning as much as an enticement. Usually served on a poppy-seed bun, and topped with sport peppers, tomato, and a pickle spear, the mother-in-law is some kind of monster mashup of a Chicago-style hot dog and a chili dog—with the actual dog swapped out for a factory-made corn-meal tamale, sold in tube form, sans corn husk (Anthony Bourdain called it a “disturbing in design, but strangely compelling”). According to street-eats lore, it got its dubious sobriquet because both varieties of mother-in-law cause angst and indigestion. Even the sandwich is a mother-in-law joke.

Is it as iconic a Chicago sandwich as an Italian Beef or a hot dog “dragged through the garden”? It is not. But it may say more about the history of the Windy City than either of them: a Mexican foundation, filtered through an African-American culinary sensibility, manufactured and sold by East European immigrants. The tamale, which has in fact been a local staple for well over a century, is the core of the mother-in-law, and because Notable Sandwiches has already tackled the history of both the hot dog and chili, the focus today—like the focus of the sandwich—will be on this Mexican bundle of mushy comfort. Henceforth, this column will be a discourse on the taxonomy of tamales.

With over 650,000 residents, Chicago is the U.S. city with the second largest population of Mexican-Americans, trailing only Los Angeles. It would stand to reason, then, that the tamale would have worked its way into the local cuisine. “It's an ancient food,” St. John’s professor Steven Alvarez told Salon.com in 2022. “It goes all the way from Tierra del Fuego all the way up to up to North America. It also has so much relevance because in Latin America, different groups have their own variations of tamales—and the same is true in the United States." Chicago has great traditional Mexican tamales, and you can also get Tex-Mex, Guatemalan, Venezuelan, Peruvian, Cuban, and Puerto Rican tamales. But when it comes to the mother-in-law, there are three distinct varieties to know: the “California style” that launched a tamale craze in the 1890s; the Mississippi Delta “red hots” that arrived in the city with the Great Migration; and the local machine-made variety that took hold over the next few decades.

The Chicago tamale’s story begins in the late nineteenth century, when the city was invaded by a small army of California’s so-called “Tamale Men,” clad in immaculate white uniforms and peddling their wares from steaming metal pails. “I am sure that to the average American at first trial a tamale seems more like a foretaste of that tropic climate, a graphic description of which has been given us by immortal Dante, than food for Cherubim and Seraphim,” wrote Sigmund Krausz in his 1891 guidebook, Street Types of Chicago. “And yet it is delicious, this mixture of chicken, olives, tomatoes, cornmeal and red pepper, if you once get used to it. Possibly you have to overcome a slight repugnance at the first trial, but this will be amply repaid by the wholesome effect of the tamale on your digestive organs and by-and-by you will be initiated into the toothsome mysteries of this steaming bundle of cornhusks… Long live the tamaléro!”

The tamale craze went national thanks to the World’s Columbian Exposition, when Chicago erected its legendary White City and played host to global humanity. The fair was ground zero for numerous noteworthy foodstuffs: the brownie, peanut butter, Pabst Blue Ribbon beer, Juicy Fruit chewing gum, Quaker Oats, Aunt Jemima’s Pancake Mix, Shredded Wheat, Cream of Wheat, and—most crucially for our purposes—tamales, the Vienna Beef hot dog, and chili (though that last one may be apocryphal).

“The United States in the 1890s was in the midst of a tamale man invasion that strolled hand in hand with the chili con carne craze,” writes Gustavo Arellano in Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America. “Their nearly universal singsong call—‘Hot ta-ma-leeees! Hot ta-ma-leeees!’—rang from Montana to Tacoma. They hit the streets with such popularity that one newspaper opined that the tamale had ‘supplanted the wienerwurst in the hearts of the people.’” Tamales supplanting wieners is the essence of the mother-in-law. The blanket of chili completes it. So the fact that the tamale, hot dog, and chili all made their Chicago debuts at the World’s Fair would suggest a natural origin point for the sandwich. Would that it were so simple.

Like most crazes, tamale-fever burned hot and fast, the white-aproned vendors soon rendered something of a joke. But in the rural South, the “red hot tamale” stuck around after the national mania petered out, and became a hallmark of Southern cooking. “Some hypothesize that tamales made their way to the Mississippi Delta in the early twentieth century when migrant laborers from Mexico arrived to work the cotton harvest,” writes Amy C. Evans of the Southern Foodways Alliance at the University of Mississippi. Smaller and far spicier than Latin-style tamales, red hots use cornmeal instead of masa (nixtamalized corn flour), are simmered not steamed, and are generally served with their cooking juices.

The Delta-style tamale—which inspired legendary bluesman Robert Johnson’s rag “They’re Red Hot”—likely arrived in Chicago a century ago, with the Great Migration. “I think about this idea that when African-Americans left the Mississippi Delta in the early years of the 20th century, they brought their music with them, and what was rural country blues became electric blues in the bars of Chicago,” historian John T. Edge told NPR in 2007. “I'm just wondering if that's what happened to tamales, which are a primary snack food in the Mississippi Delta, especially among African-Americans, if, when they came north, they brought tamales. And tamales and Chicago-style hot dogs had a baby, and that baby is a mother-in-law.”

Unfortunately for this theory, the tamale used in a mother-in-law bears little resemblance to “red hots” or to “California chicken” tamales. A machine-extruded cylinder of corn meal and spiced beef paste, bound not in corn husks but in paper or plastic, the Chicago-style tamale is closer to a mushy corn dog than it is to the traditional Mexican variety. But this is the version used in a mother-in-law, produced by three rival Windy City tamale manufacturers: Supreme, Tom Tom, Veteran, founded by immigrants from Armenia, Greece, and Poland, respectively. “To this day,” says Arellano, “the tamales of Chicago and the Mississippi Delta are the only American-born, non-Mexican-dominated tamale traditions that date back to that era, enjoyed only in their regions, accepted long ago as uniquely theirs.”

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

Chicago-style tamales have been sold alongside hot dogs since at least the 1930s, so it’s not outside the realm of possibility that the first mother-in-law was born by the middle of the last century. In 2007, Tom Tom Tamales owner Nick Petros told the Chicago Tribune that when he was growing up on the South Side in the ‘50s, he remembers vendors selling them from their pushcarts. Another source pegs the origin to a long-closed restaurant named Leo Castle in the 1950s. The proprietor of Fat Johnnie’s hot dog stand, John Pawlikowski, put the mother–in-law on his menu in 1972, and reigned as Chicago’s foremost booster of the sandwich until his death last year. As for the origin of the name, that’s a bit of a mystery. According to a 1987 article in the Bellevue Democrat, restaurant owner Frank Crossin specialized in sandwiches “such as the mother-in-law, named after his wife's mother. The sandwich is a hot tamale with chili and onions.” Frankly, it’s a weird combination of ingredients to slop together and name after your mother-in-law. I guess the joke was on her.

Actually, judging by most of the reviews I’ve read of the sandwich, the joke is also on the eater. It sounds undoubtedly flavorful, but also profoundly…mushy. In her essay on the guajolota, (aka: Notable Sandwich #77) Talia paid loving tribute to the pleasures of mush, but when it comes to sandwiches, I believe in structural integrity. The guajolota is served on a hard-crusted bollilo roll, whose crunch contrasts with the overwhelming squishiness of the mother-in-law. As Gustavo Arrellano’s describes the latter, “the tamale absorbs the chili, transforms into a ruddy-yellow vessel that spills out of the hot dog bun, which labors to keep its innards inside and fails, like a Dixie cup trying to hold back Lake Michigan.”

Given that mother-in-law jokes are staler than a week-old hot dog bun, perhaps the quality of the sandwich is appropriate. But Chicago is the improv comedy capital of America, and if the city is going to have a joke sandwich, it should probably be funnier than a mother-in-law joke—“The last time she made me lunch I asked for something light. She brought me a vinegar sandwich and a 30-minute lecture on my life choices”… “What's the difference between a mother-in-law and a vulture? The vulture waits until you're dead before picking your bones!”… “How many mothers-in-law does it take to change a light bulb? None. They prefer to criticize your lighting choices instead”— among the lowest forms of humor around. But I don’t mean to be too judgmental. That’s my mother-in-law’s job.

-

it is wonderful to see you are back!

-

Good stuff. I lived in Chicago for seven years- 92 to 99 - never heard of or tried this sandwich. Pizza puff? Sure, but now I’m sad I never tried it. I did live in Pilsen, the Mexican heart of the city, so maybe that’s why it wasn’t a thing. Anyway, nice to see you both

Add a comment: