Notable Sandwiches #121: Monte Cristo

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where I, alongside my noble editor David Swanson, plunge fearlessly into the mysteries of Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week, a French-toast treat: the Monte Cristo.

The Monte Cristo sandwich is, first and foremost, a descendant of another sandwich: the illustrious croque-monsieur. The croque-monsieur is something like the national sandwich of France, a ham sandwich topped with melted Gruyere grilled under a broiler. The Monte Cristo is much the same, but—in an American flourish—it’s dipped in egg and fried (like French toast) and often served with maple syrup and/or jam. I had a particularly dismal exemplar for research, which was tepid, oily, topped with unnamed “breakfast syrup” and heavy with undistinguished ham; however, I appreciate that done right, with good jam and good cheese, it could be a delicious indulgence.

The Monte Cristo’s origins are somewhat vague, as is all too often the case in sandwich history; what is certain is that it is more than a century old. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America places its first mention in an unnamed “American restaurant industry publication” in 1923. The earliest primary source my intrepid editor David could find is from 1924, courtesy of Chef A. L. Wyman, who boasted of having picked up cooking techniques in “the Orient” and having “studied the food of all climates and races”. He also operated a “laboratory-kitchen at Glendale” for his Los Angeles Times food column. That’s where he advised readers to prepare a Monte Cristo:

Cover six slices of sandwich bread with a slice of American full cream cheese, cover the cheese with slices of boiled ham, cover with slices of bread, tie with white string, dip in beaten egg and fry a nice brown on both sides in hot butter. Place on hot plates, remove the string and serve.

(Nota bene: “Full cream cheese” here means any full-fat cheese rather than cream cheese.) At any rate, subsequent generations have embroidered this recipe with maple syrup, jam, powdered sugar, other meats like turkey and tongue (the tongue version is called the Monte Carlo, for some reason), and probably dispensed with the string. But the basic recipe remains the same.

Chef Wyman doesn’t claim to have invented the Monte Cristo, and in fact devotes a lot more space to his innovations with Swedish fruit candy in the May 24, 1924 “Practical Recipes” column. Nor does he divulge why, precisely, this particular sandwich should be named for an island in the Tyrrhenian Sea, populated mostly by goats. The sandwich’s long association with California, however—and the similarity of the Monte Cristo to the croque-monsieur—brings up an obvious suggestion: this is an homage to that Frenchest of French books, Le Comte de Monte Cristo, published in serialized form by Alexandre Dumas between 1844 and 1846. Or more probably: an homage to one of the silent-movie versions produced in 1913, 1918, or 1922. It’s a very French novel, and this is a desperate-to-be-French sandwich. Pourquoi pas? The Monte Cristo sandwich is certainly elaborate, although, unless your target is vegetarian, celiac, and visually impaired, not an especially potent vehicle for revenge—which is a dish best served cold, in any case.

Revenge is the keystone of its namesake, The Count of Monte Cristo, the book which made said goat-strewn island famous, and which has transcended its niche in time as a tale of post-Napoleonic vengeance and passed into that elusive stratum of artistic immortality. The novel, which is a gargantuan 1,500 pages—Dumas had to come up with a lot of material to keep the serialization money flowing in for two whole years—has been adapted at least twenty-two times to film, and an additional several dozen times for television. These include anime serials, lush Bollywood musicals, a Soviet drama, a kung-fu-and-cocaine version called Legacy of Rage, and a lot of straight-laced, and relatively straightforward, adaptations in French and English.

The theme is simple: an innocent man wronged, who obtains a fortune, and returns to exact elaborate revenge on those who betrayed him. (Or her: like I said, there are a lot of variations on the theme.) The latest—a lushly filmed, often unintentionally comic three-hour French extravaganza which came out in June of 2024 and is playing in the US this winter—proves the curious durability of the baroque tragedy of Edmond Dantes, which is coming up on two hundred years of being adored, adapted, translated, devoured. (In addition to last year’s big-screen production, there’s also an English-language limited series starring Sam Claflin and Jeremy Irons that has yet to hit streaming services. Given the sheer volume of adaptations, it’s not surprising that at least one should be a sandwich.)

Of course, none of the versions are even close to comprehensive. That’s because it’s an incredibly complex novel—see above re: 1,500 pages and two years’ worth of juicy cliffhangers, plot snarls, and wild twists to keep those magazines selling. (As Lucy Sante has noted: “Dumas was notorious for exploiting the practice of payment by the line, garnishing episodes with lengthy monosyllabic conversations, which ultimately caused newspaper owners to devise other standards for payment.”) The lust for adaptation long precedes even the advent of film; Dumas himself adapted it for the stage no less than three times. Ever since, it’s continued to find its way onstage in multiple languages, including in lavish musicals. (No operas, yet, which frankly shocked me.)

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

I first read The Count of Monte Cristo in my teens, and throughout the subsequent decades, certain images—the stark island prison of the Chateau d’If; Dantes’ fellow prisoner and mentor Abbé Faria making pens out of fishbones; the wealthy Danglars taken captive by bandits, and forced to spend his entire fortune on fowl and bread to avoid being starved to death—have stayed with me ever since. At age fourteen or fifteen when I read it—only a few years younger than Dantes at the start of the book—I was swept away by the passion of the narrative, the love won and lost, the righteousness of the great vengeance. The primary impression it left in my mind was a vast soaring arc of emotion.

Revisiting the novel in adulthood, I’ve been struck by it in an entirely different way. I’ve mentioned the serialization and money a few times in this column, and it’s for this reason: this is an absolute potboiler. It’s pulp fiction! It’s high melodrama, and something crazy happens roughly every five pages. To take just one short sequence: it’s not enough that Dantes escapes the island prison in the burial shroud meant for his mentor, and is cast into the sea. He’s then immediately caught in a thunderstorm, washes ashore on a deserted island, watches the crew of a fishing boat drown in the maelstrom, and winds up hailing a ship that turns out to be run by Italian smugglers, who immediately recognize his superior skills as a sailor and accept him as one of their own.

All this happens in, like, three chapters! That is an entire book’s worth of stuff happening, and there are 117 chapters, not a single one of which is a snoozer. Everything happens that could conceivably happen, plus plenty of stuff that stretches the limits of conceit. There’s the specter of infanticide, the rise and fall of Napoleon, a wife who, entirely separate from the Count’s elaborate revenge plots, is serially killing off her husband’s family with poison. There’s dramatic suicide, duels, slavery, Italian bandits, countless disguises, and, of course, romance, in forms from the poisonous to the saccharinely pure.

Contemporary audiences loved it. They couldn’t stop talking about it! It “drove Paris into a frenzy,” according to one literary historian. Serials were all the rage, and Dumas shared the pages of the Journal des Debats with Victor Hugo and Jules Verne, among many others. And he was beloved; his work sold like hotcakes. Why not? There’s vast wealth, sex, drugs (an emerald box full of opium-hashish pills!), murder, betrayal, and redemption. Everything you could want, in one hundred and seventeen racy chapters, and an accordingly baroque complexity. How it ever gained the reputation as a stuffy, moralistic tome is beyond me.

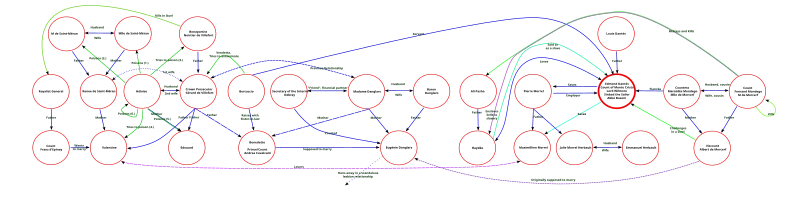

Here’s a chart of the characters and their relationships in the novel, which is byzantine (in the sense of complex) and Byzantine (in its relentless Orientalism, reflecting French popular obsessions at the time):

No film—not even this year’s three-hour epic—could possibly approach this level of complexity, and would be foolish to try. I watched the new movie for this column (I’m dedicated!), and it was, despite taking itself quite seriously, absurd: the Count appears as a sort of nineteenth-century Batman, in a black swirling cape, and his various disguises are achieved by means of Mission Impossible-style latex prostheses. Rather than conventionally aging the Dantes actor, Pierre Niney, or even just letting him grow a beard, he’s adorned with plastic until his long bloodhound face bears an uncanny resemblance to Pedro Pascal. (You could also just cast a different guy for the callow youth and the prematurely aged escaped prisoner! You could do that!)

The film’s best innovation is turning the infamous prison cell into an oubliette, lending the setting a hallucinatory quality, with snow falling down the long shaft of the bottle dungeon that holds Dantes in a kind of living death. Past that revelatory sequence, lots of corners are cut (I’m still mad none of the adaptations I’ve seen include the homicidal Mme. de Villefort), but more to the point, the Count’s brilliance and malevolence are dimmed by these prosthetic machinations. This is how you know I rather liked the film: I’m bothering to quibble with it! It wasn’t terrible, but it wasn’t amazing, and Monte Cristo should be amazing. It should knock you on your ass. The book always does, no matter how many times you reread it.

There are, of course, those snobs who dismiss Monte Cristo for the exact reasons I detailed above—it’s a potboiler. It’s for kids (homicidal kids, maybe); it’s no better than a comic book; it’s pure puffery and melodrama. This is partially a straw man; encountered via film or TV, you’re inevitably dealing with adaptation and abridgement. There are countless abridged textual versions of Monte Cristo as well, and initial translations left out a lot of the sex and all of the drugs, and perhaps some of Dumas’ more sanguinary impulses as well. And maybe it isn’t! This is a real egg-dredged jam-and-ham kind of a story, one to satisfy even the mightiest appetite. Appropriate to its son the sandwich.

But fundamentally, what draws people to this tale again and again is its central fantasy: that of the powerless individual made powerful, and able to destroy his enemies with a ruthless omnipotence. What makes the Count’s revenge so attractive is that, for the most part, his principal lever is the misdeeds of his enemies. He drives them to suicide and insanity by teasing out the threads of their own consciences, by playing on their guilt, their ambition, their greed, and even their love of family. Unlike the inevitably simplified film versions, the villains who condemned Dantes to the dungeon are terrifying precisely in their banality: they are motivated by ordinary greed, ordinary ambition, ordinary lust and drunkenness.

You’ve met men like Mssrs. Danglars and Villefort and Mondego, men who will trample over anyone to achieve their petty aims. They’re fundamentally human, with family ties and careers. They’ve committed an unspeakable act, and accordingly go on with their lives, not speaking of it, and prospering. They control the law with their money and their reputations. Yes, we’re very familiar with such men, these days; there’s an unbroken line between those days to these made up of such careless wasters of other people’s lives, such ready despoilers of the happiness of others. The fantasy of the Count is being rich enough, smart enough, and powerful enough to make these provincial elites tiny in comparison, sure—by at least one calculation, the Count is a billionaire by the end of the book, well before that was even a conceived thing, let alone a weird semi-feudal class semi-openly running societies.

But the real fantasy at the heart of Monte Cristo—and what makes me keep returning to it along with all those playwrights and filmmakers and artists and animators—is the fantasy of justice. It’s the wronged man, the victim, rubbing the faces of his abusers into their own crimes; it’s the refusal to be cast away, the combination of the ability, the means, and the desire to right such a fundamental wrong. From a man who cannot even see the sky from his dungeon, Dantes becomes a bolt of vengeance sent from heaven. And because injustice continues, and multiplies; because those who wrong others continue to benefit from it; because the cruel use any means to perpetrate their cruelty—well, the fantasy of destroying them utterly, these ordinary heartless men, has endured for nearly two hundred years. The fact that fantastic resources are needed to enact such justice against the powerful is, amid all the fantastical elements of the story, apropos. The scales are so cruelly tipped that it takes a wonder-tale to reverse them.

That is a story that will likely never lose its appeal—and particularly now, particularly here, amid the triumph of the most brazen and venal, the cruelest and the most careless with the hearts and bodies and lives of others. It’s a story we’ll keep wanting to dust with sugar and consume, in all its rich and magnificent heaviness. Unless some miracle occurs and the justice we are parched for falls like rain, it will still pertain a hundred years from now, and a hundred more.

-

Jeez, after all that literary exegesis, I feel a little dopey talking about my Monte Cristo encounters but in Boston, in 1973, the sandwich, as prepared in at a few places on Commonwealth, was turkey, ham and Swiss on challah dipped in batter and deep fried. It was savory, not French toasty at all. It crunched. Since then, all I encounter is as you describe. Ah youth, ah my crunchy youth.

Add a comment: