Notable Sandwiches #120: Montadito

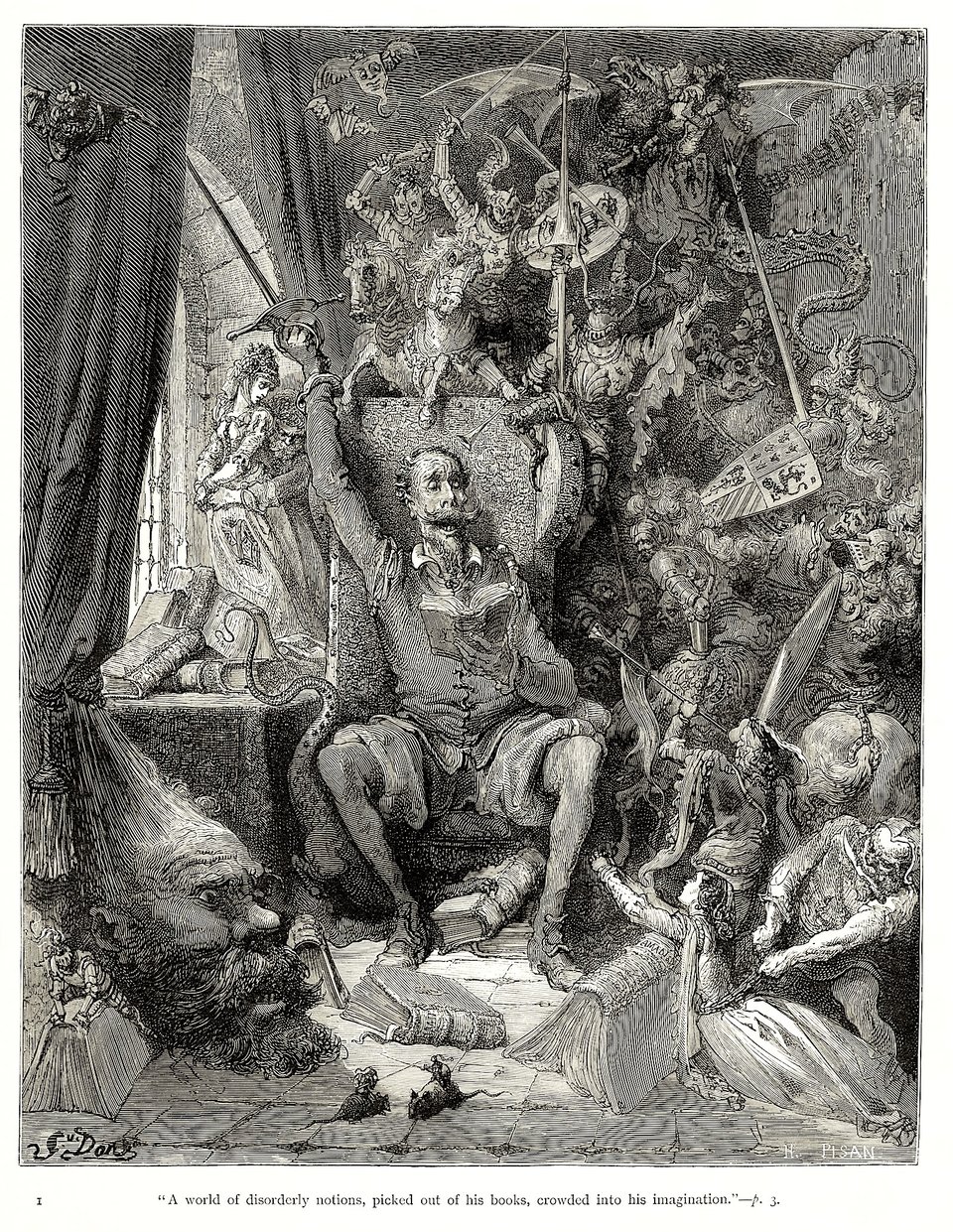

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, where I, alongside my heroic editor David Swanson, tilt at the windmills that comprise Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches. This week, a humble Spanish treat: the montadito.

“To talk about montaditos,” the Spanish publication Gurme Sevilla declared in 2018, “is to start and never end.”

Rest assured that won’t be the case with this column, as tempting as it is to start talking about a sandwich—even one so unassuming as the montadito—and never stop, to delve into a more pleasant and starchier world, and remain there. This sandwich, in particular, is both expansive and minute: it’s a tapa, a little bite on good Spanish bread, frequently served with some variant of Spain’s ubiquitous pork inside. But the varieties are endless.

There is a restaurant chain in Florida with the evocative name of 100 Montaditos (although the menu, online, offers a still-impressive 93). Montaditos with croqueta de jamon. With tomato and olive oil. Calamari. Basque sausage and aioli. Morcilla—blood sausage—and red onion. Tortilla espanola and chorizo. Croqueta de bacalao. Croqueta de manchego. If this were a stall I would wander it in wonder. From afar, I look at it with hunger. How long would it take me to eat one hundred montaditos? Taken slowly, it’s a task you could start and never end, lingering over the ones you loved, and returning, and then going on your pleasant way.

There are no storms of fire here, no bitter winter, no impending civilizational collapse, no trade of vicious blows or ugly conspiracies. Here there is just warm bread and endless variety, and in each bite the implicit sunshine of Seville, Cadiz, Barcelona. Here, of course, people work, and people suffer, but not us. We are here to take our ease, and eat bread in olive oil with thinly sliced morcilla, or with pringa, the long-stewed, paprika-scented pork that falls tenderly apart at a touch. A ripe tomato falls from the vine ready-sliced, onto chapata bread. No one asks us for any money, and there’s music. The cobbles are sun-warmed. It’s good here. Let’s stay.

There’s little but folklore to prop up the history of the montadito. Vague rumors of fifteenth-century origins, of humble fieldworker’s fuel to be carried into the hot fields of Andalusia and Extremadura: a laborer’s respite. Meat and bread have come together many times throughout history; it’s not especially difficult to imagine the scene, although presumably this weary laborer—coming perhaps from the grape arbor, or the wheat field, or from pig-herding with his stick to shake the acorns down for the pigs to root—would not be content with a mere bite.

The montadito’s diminutive size, then, is owed more to the tradition of tapas, those small dishes ubiquitous most everywhere in Spain: fat olives in ceramic dishes; salt-soaked almonds; bites of omelette, sausage, fish, some no bigger than a coin, but each for a dollar. Once you start, you could go on forever, deep into the night with a glass of wine, or several…

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

The recorded history of tapas has more to offer than that of the montadito, but not much that’s more definite. Tapas comes from tapar, to cover, and one origin myth has it that these snack-sized bites were originally slices of ham or cheese, used to cover glasses and prevent flies from getting into the wine. Another theory: before most travelers could read, enterprising barkeeps presented an array of dishes on a pot-lid, an edible menu.

Yet another, and most common: Alfonso the Wise (1221-1284), King of Castile, Leon and Galicia, was once entreated by his physicians during an illness to take only small bites of different dishes of food. Having survived the disease, he declared it healthful for tavernkeepers to provide similarly modest offerings to their clientele, so that even the poor wouldn’t have to drink on empty stomachs. (This innovation is also claimed to have originated centuries later, under the reign of Felipe III, to subdue unruly soldiers and sailors. With snacks.) Rather more is known about Alfonso the Wise’s policies towards shepherds, law codes, astronomical treatises (including the Alfonsine tables, which provided data helping to calculate the position of the sun and moon in relation to the stars) than any concrete decree about the tapas. But modest as they are, they are endless, multiplying like a field of stars across the whole country, rows of white dishes gleaming at candlelit streetside tapería.

Supporting the theory of Alfonso the Wise’s illness, in Don Quixote, Sancho Panza encounters a surreal version of a tapas spread, intended mostly, it seems, to ridicule the eccentricities of seventeenth-century doctors.

The scene is lengthy, but begins like this:

The history says that from the justice court they carried Sancho to a sumptuous palace, where in a spacious chamber there was a table laid out with royal magnificence. The clarions sounded as Sancho entered the room, and four pages came forward to present him with water for his hands, which Sancho received with great dignity. The music ceased, and Sancho seated himself at the head of the table, for there was only that seat placed, and no more than one cover laid. A personage, who it appeared afterwards was a physician, placed himself standing by his side with a whalebone wand in his hand. They then lifted up a fine white cloth covering fruit and a great variety of dishes of different sorts; one who looked like a student said grace, and a page put a laced bib on Sancho, while another who played the part of head carver placed a dish of fruit before him. But hardly had he tasted a morsel when the man with the wand touched the plate with it, and they took it away from before him with the utmost celerity. The carver, however, brought him another dish, and Sancho proceeded to try it; but before he could get at it, not to say taste it, already the wand had touched it and a page had carried it off with the same promptitude as the fruit. Sancho seeing this was puzzled, and looking from one to another asked if this dinner was to be eaten after the fashion of a jugglery trick.

The doctor keeps smacking Sancho with his whalebone wand, and refusing him dishes (fruits, partridge, rabbit, meat-and-vegetable stew, veal with pickles). Eventually, tired of the whole thing, Sancho says: “Get out of my presence at once; or I swear by the sun I’ll take a cudgel, and by dint of blows, beginning with him, I’ll not leave a doctor in the whole island… And if they call me to account for it, I’ll clear myself by saying I served God in killing a bad doctor—a general executioner. And now give me something to eat, or else take your government; for a trade that does not feed its master is not worth two beans.”

Fortunately, before engaging in medical mass murder, Sancho is distracted by an urgent letter, and makes do with travel rations of a piece of bread and four pounds of grapes.

But being neither kings nor heroes of legend, let alone heroes of literature, we are immune to these intemperate and foolish physicians. We are not forced to make codes of laws, or track the moon in its course. We are only bid to dream of montaditos, a hundred montaditos, a thousand montaditos, a road paved with montaditos.

Woebegone as we have become, we punish ourselves even for dreaming; even for a fleeting glimpse of respite. Though we are hungry for joy as any famished laborer is for his repast, we feel guilt at granting it to ourselves while others suffer. But I tell you there is no harm in this gallery of imagined montaditos: there is no sin in dreaming of fat olives and Seville oranges still in the trees, and you at table, with no task but to choose among an endless bounty of good things, soft bread, and small savory things—briny cheese and wafer-thin jamón ibérico and a perfect egg and soft hot pringa and garlic and tomatoes—to fill them, fill you.

Only from plenty can we imagine plenty: a world where there are infinite montaditos for everyone who hungers; a soft place to sit, and dream, while the sunset cools to twilight, and then shadows grow deep and warm, and we are sated at last. I would invite all the world to such a table, and rejoice in their plenitude, and my own. If I forbid myself to dream it, no such table will ever exist. There is no benefit to starving your heart, to force yourself away from your mind’s feasting. So come sit with me, in this sunny alley with its old stones and new wine, a platter of olives before us, and montaditos in plenty. To start, here, is to never truly end: it is a place to return to, whenever you wish.

-

Yes please, I wish to be subdued with snacks! :) Great piece, Talia!

-

Gorgeous journey you take us on here, Talia, leading me both to the library and the fridge. Thank you!

-

Yes, what Michele G said! (but in my case replace library with links and fridge with doordash)

-

I’ll be there! It sounds wonderful.

-

What a wonderful, mouth and imagination watering column. Thank you Talia.

-

What a wonderful, mouth and imagination watering column. Thank you, Talia;

-

What a wonderful, mouth and imagination watering column. Thank you, Talia.

-

Each and every word read here is like a succulent and light bouchée that feed sumptuously the brain, making it grow infinitely, reaching intriguing skies, passing trough squall's and lightning's, approaching an human harmony that we sometimes forgot it exists. Many thanks Talia Lavin!

-

Jolean and I have been l living on the Costa Blanca, mostly, since January but I couldn't even begin to guess where I could find this information, both literary and tapa-cal. We find bocadilla available more than montadito. The thin slice of bread with savories atop is seen more at purveyors of pintxos.

-

Beautifully written, Talia - thank you!

Add a comment: