Notable Sandwiches #119: Mollete

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, where I, alongside my heroic editor David Swanson, pick our way across the bracken-strewn fields that comprise Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches. This week: a Mexican comfort food, the mollete.

December end of year note: Fewer than 10% of you are paid subscribers, but you can change this—and bring light and joy to our lives—for a mere $5 a month, which entitles you to a whole extra column every week and our eternal gratitude. Seriously, I want to smooch every new paid subscriber. So if you enjoy the below, or anything else we write, consider shelling out a bit—or giving this subscription as a gift!

Right here, in the pinch of winter—one day away from the solstice, so deep in the deepest heart of the thing—we’ve come to, as you could say if you were pushing a metaphor, the sticky center of the sandwich. The part where even the most dedicated gourmand might tire mid-bite, where the dish that seemed so delectable on the menu turns out to have suspiciously crunchy bits and an unidentified watery sauce, where the starch glues your mouth shut, and you’re regretting leaving the warm bower that is home for any reason at all. In short, it’s the time of the year when various religious and indigenous traditions spin up festivals of light in a fevered attempt to keep the dark out long enough for the days to lengthen.

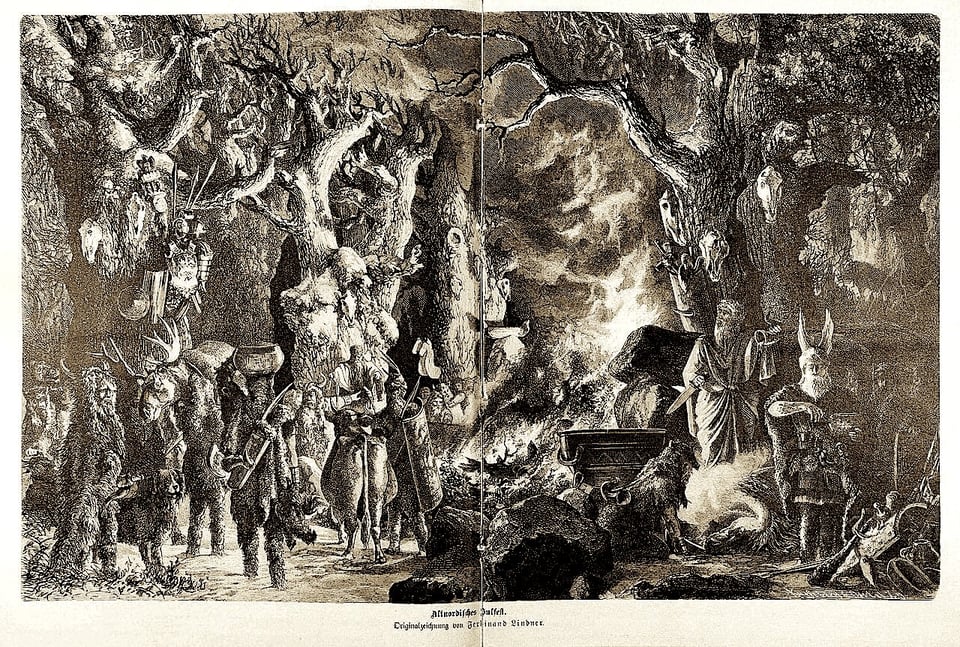

A sanitized, corporate-friendly holiday season is all well and good, but there are some truly magnificent midwinter celebrations, often the sort that involve the birth and/or death of a god. You don’t have to look that far: Yule, as practiced by the pagan Northern Europeans before Christianization, involved, among other things, swearing sacred oaths on sacrificial pigs (hence Christmas ham) as attested in the ancient song cycle the Poetic Edda:

“Heðinn was at home with his father, King Hjörvarðr, in Norway. Heðinn was coming home alone from the forest one Yule-eve, and found a troll-woman; she rode on a wolf, and had snakes in place of a bridle. She asked Heðinn for his company. ‘Nay,’ said he. She said, ‘Thou shalt pay for this at the king's toast.’ That evening the great vows were taken; the sacred boar was brought in, the men laid their hands thereon, and took their vows at the king's toast. Heðinn vowed that he would have Sváva, Eylimi's daughter, the beloved of his brother Helgi…”

Things don’t end well for Helgi, or, presumably, the boar. Ullr, a Norse god of scant fame and little mention, presided over snow and sometimes Asgard during Odin’s wintertime absences, possibly dwelling in a yew forest. A 12th-century text says the god was inspired by a particularly cunning wizard who used a bone-chariot to get from place to place. At any rate, Ullr is currently one of two deities who are patron saints of skiing—it’s him and the mountain giantess Skaði, disgruntled ex-wife of a sea-god who went back to the mountains to seek snow, and who presides over the slopes.

In Slavic traditions the solar/chthonic deity Dazhbog, sometimes appearing as a wolf or a goat, and the spirit of the newborn sun, Koliada, reigned over midwinter, and the peasants built great bonfires and invited the dead to warm themselves at the flame. In Novgorod, Kikimora—a spirit in the form of a woman with long bare hair, seated at a spinning wheel—appeared, at Yuletide, to those who would soon die.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

In Yakutia—a region of Siberia that is staggeringly large and very, very cold—midwinter is presided over by Chyskhaan (or Jyl Oghuha), the Frost Bull, a god of the indigenous Sakha people. He emerges from the Arctic Ocean, and with his fearsome breath drives cold before him, the true deep arctic cold of the long night. When the weather warms his horns drop off, first one, then another, and then his head—only to be reborn again when the sea is cold enough.

The Maya, who had perhaps less reason for excitation over extreme cold, nevertheless marked the winter solstice in a way concordant with their love of complex calendars. At an ancient temple complex in Guatemala, three Mayan pyramids—one for the winter solstice, one for the summer solstice, and a central one for the equinox—were constructed in such a manner that on each of these phenomena, their respective pyramids were clothed half in light, half in darkness.

The Mayan sun god, Kinich Ahau, faced an arduous journey to his return each day: down into the belly of a monster, in the depths of the sea, and back up to the sky again. His increase was the increase of life, and to be celebrated. The Aztec god of frost, Itztlacoliuhqui, had a face made of a curved obsidian blade, and no eyes. He was once a god of the dawn, who shot an arrow at the sun and was punished to rule over frost and stone forever. In his hand he carries a straw broom: to clear the way for new life.

Here in New York there are no troll-women or spinning spirits or frost-bulls or blade-headed gods—at least none that I’ve seen recently around the neighborhood. There’s just a long sunless stretch of driving cold rain—which should be snow and isn’t—and intermittent periods of cheek-pinching chill. The draining out of light from the world has been all too mundane, and seems hardly to merit the death or rebirth of any god at all. Unless there’s a spirit of gloom and general dread. (Oizys in Greek, or Miseria in Latin, was some sort of personification of distress and sadness, a daughter of the night-goddess Nyx, but she has no myths of her own—just a colorless entry in Hesiod’s Theogony.) This sort of mood drives me away from myths to Melville, to that famous opening paragraph:

“Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off—then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can.”

Sadly, Melville’s cure for seasonal affective disorder—a berth on a whaleship—is somewhat in short order these days. (Not that I wouldn’t mind squeezing the sperm with the right harpooner, if circumstances were different). So I turn away from mythology, Melville, and melancholia to the nominal subject of this column—the mollete.

It’s a bright little sandwich, a comfort food—made of half a soft bolillo roll, topped with refried beans, fresh cheese, then grilled and topped with pico de gallo, a sparkling tinkly taste if ever there was one. It’s home and nostalgia and cheap fare for students for so many people, a little piece of sunshine on a plate. It’s no coincidence that so many of these midwinter rites involve prayers for the return of the harvest, the Yule-goat made of the harvest’s last sheaf, a corner of a grainfield left and propitiated with ribbons and salt in hopes of the return of gold fields, and their yield of bread.

So there it is, los molletes: the sun reborn on the plate, warm and heavy in the palm; food writer Pedro Reyes calls it “simple, cheap but perfect.” The toasty crust and the soft bean and the gentle vegetal acidity of salsa—all easily made and proffering a rare coin in this season, which is satisfaction, and warmth, and a little bit of joy.

My dry little addendum is that mollete is pronounced, more or less, like “moiety,” which is a fancy word for “half”: halfway through the cycle of the sun and season, nearly at the turning point, nearly at the increase of the light. We are closer than we know to its return, to the death of the bull, the return of Odin, the interruption of Itzlacoliuhqui and his cold broom. Make yourself a mollete and celebrate this moment of increase and return. And put a little crema on it—a rich little dollop, for more life, and more light.

-

This was a fun journey, finishing with a sparkling tinkle

Add a comment: