Notable Sandwiches #116: Melt

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where I, led gently by my brilliant and long-suffering editor David Swanson, wade through the rough waters of Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week, in all its cheesy glory: the melt.

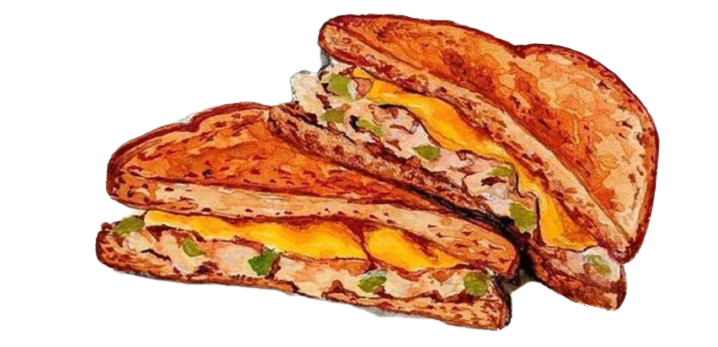

The title of this essay is not an instruction, although this week it might as well be. The “melt” is a catchall title rather than a singular sandwich; it describes that category of dishes—among them the patty melt and the tuna melt—that judiciously combine bread, protein, and a substantive layer of melted cheese. There’s no fixed point of invention for this innovation, although the tuna melt in particular has many fathers, along with all the apocrypha that inevitably accrue around any great culinary success.

As with many of our subjects, there’s an element of sandwich semantics here: although “melt” as an adjective is relatively new by all accounts, dating to perhaps the mid-twentieth century, attestations of the Welsh rarebit, an open-faced cheese toast sometimes served with proteinaceous addenda, have been around since the 1700s. But a closed-faced and an open-faced sandwich are by no means two sides of the same coin. They are separate phenomena, and should be treated as such by us, committed, as we are, to the full spectrum of sandwich studies.

There—I put my serious-sounding hat on, the one that let me introduce myself once, semi-seriously, to a public gathering as a “sandwich historian.”

But this column will be light on history, heavy-handed with the feelings, a thin foundation of substance smothered by a molten layer of sorrow. Because the truth is, during this spectacularly shitty week, the melt truly feels more like a directive than just a name. I’ve spent the past few days exploring new ways of fusing with my bed, a mixture of apathy, grief, and the careful construction of a carapace of numbness preventing me from moving. There has been nothing delicious about this process. It’s ugly, and it’s sad.

This is a bad week to be someone who cares about things, a faculty I have tried to cultivate in myself for my entire adult life. Someone who cares about women’s freedoms, who cares about trans rights, who cares about food safety and climate change and democracy—in short, someone who had the capacity both for naive hope before Tuesday, and for a broad and deep sense of betrayal.

However much I tried to temper my expectations, I did allow myself to hope—that the future could be better. That the horrors I’ve spent the last decade of my life examining, in my other life as a spelunker into the abyss of the American right, would finally begin to recede. Instead the cracks opened up right under my feet, and yours; I felt the earth buckle and go. None of the paths forward are safe. And none are comfortable.

So why not melt?

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

The leftist aphorism that “a better world is possible” feels distant now. The truth is it always did. Anyone who takes a longer view of American history than the 1930s-1970s era of New Deal economics and hard-fought social freedoms knows that revanchism, blood, and cruelty—leavened with varying degrees of populism—are more consonant with our past than that brief upward blip to freedom. That those who have fought for their rights in this country nearly always did so in the face of public contempt and very real physical danger to their persons alike, the one complementing the other.

Awakening to the collapse of the American Republic doesn’t mean giving up, but it does mean abandoning a certain image of our nation as a beacon of inevitable progress, a shining city on a hill that could ultimately never betray but only be betrayed. I think, on balance, it is better to discard this myth—because that’s what it always was—than to cling to it against all evidence, much of that evidence being the bones of our forebears. There are ideals to fight for, but principally they must reside in each other, not in a fiction of a nation whose flaws are always transient and whose institutions match resilience with capacity for change. That’s not the country we live in. And it just told us so, again.

This does not absolve ourselves of the responsibility to rescue one another. It is going to be a long bitter cold for people who care about things; and it therefore devolves upon us to lend each other comfort and warmth when we can, the little sun of the warm melt given from one hand to another.

It is also incumbent on us, I think—or at least on me—to deal with this grief honestly. To face it head-on, and feel it in all its tremulous depth, with appropriate periods of dissociation as necessary. Not doing so would inevitably allow that emotion, denied its proper outlet, to explode into anger, to break fragile coalitions, to resort to the ferocious and futile cruelties of grief deferred.

To let grief rot under a thick strata of self-denial in the conviction that emotional abstemiousness equals virtue—that sincerity, even in pain, is a sign of weakness—is a recipe for something rancid and cruel. You have to let yourself melt, feel fully the loss of possibility and wiggle room and safety and time, before you can renew your strength. Only then can you be warm and soft and present, be necessary, as small good things are necessary. Grieve with your whole self so you can offer yourself to those who need it most, when you must.

A bad time is coming. Now is the time to melt a little. Retrench. And harden for the long struggle, because a better world, despite all indicia to the contrary, still is possible. And when it comes, because we make it—when we put our hands to the wheel and make it so—it will be filling, and bedecked with cheese, and topped with parsley, and it will feed us all.

-

I've been craving a melt lately. Now I know why

-

Beautiful and nourishing, Talia.

-

Thank you for this.

-

Thank God you're still here, and thank God you're still doing sandwiches. I can hold on if you can.

-

Beautiful and nourishing!

-

Thank you for the much needed sandwich.

Add a comment: