Notable Sandwiches #114: Meatball

By David Swanson

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where Talia and I travel down the trail of Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. Before we get to this week’s column: if you haven’t bought “Wild Faith” yet, now is your chance. And if you’re looking for lighter read, ”The Best American Food and Travel Writing 2024” is out next week, featuring a notable sandwich essay from none other than Talia Lavin herself. Now, an Italian-American classic: the meatball Parm.

“If the meatball parmigiana hero were a Southern dish, scholars from Chapel Hill, N.C., to Tallahassee, Fla., would hold academic conferences every six months just to talk about it,” wrote New York Times restaurant critic Pete Wells in 2012. “If it were a Florentine dish, the Four Seasons would have it on the menu for $95, or $55 without white truffles. But it is an Italian-American dish.” Last month, Wells called it quits after twelve years as New York City’s most influential food writer, but this judgment from early in his tenure stands as among his most enduring observations. Continuing this reverie, he notes that the meatball parm “is at home on Wooster Street in New Haven, Atwells Avenue in Providence and Salem Street in Boston. It cannot be ordered at any restaurant that uses a truffle shaver. The closest thing to an academic symposium in its honor would be the lectures on the Food Network given by Prof. Giada De Laurentiis.”

This was one of the very first reviews in Wells’ critical tenure, and he was reviewing a new sandwich shop in Little Italy called, aptly, Parm, which aimed to use the meatball sandwich as the foundation for a culinary empire—and as a means of elevating classic red-sauce cooking to the center of American dining. And it worked: over a decade later Parm’s owners, Rich Torrisi and Mario Carbone, are among the most successful restaurateurs in America and beyond. So how did the humble meatball conquer the world? And, perhaps more to the point, how did the meatball become an international symbol for Italian-American culture in the first place?

In fact, the meatball didn’t have to conquer the world because it was already everywhere. The earliest known meatball recipe is for kofta, a Persian dish that consisted of ground lamb, egg yolk, and saffron. The ancient Roman culinarian Apicius included several meatball recipes (“isica”) in his first century cookbook, De Re Coquinaria. And the recipe for “Four Joy Meatballs”, a favorite in Qin Dynasty China, dates from the 2nd Century B.C. That version is made from minced pork, ginger, lotus root, onion, wine, pepper, and soy. You can still get them today. Wikipedia’s list of meatball dishes includes over forty varieties from around the globe. (Maybe that can be Talia’s and my next project; I’m dying to give haggis meatballs a try.)

But what we talk about when we talk about meatball sandwiches is the version that Pete Wells hailed in that review from over a decade ago, and this archetypal 21st century meatball is a distinctly Italian-American creation. To be sure, there are meatballs in Italian cooking—have been since the days of Apicius. “In Campania and Calabria and Basilicata and Sicily, meatballs most certainly did exist,” writes John Mariani, author of How Italian Food Conquered the World. “But they were small, about the size of a marble, and were called polpette, which literally means ‘little meats’ and derives from the Latin word for ‘flesh.’ (In Sardinia they’re called ombixeddas, ‘little bombs.’) They were commonly served in between layers of many other ingredients in lavish pastas dishes like lasagne and timballos.” This was simple food. In Pellegrino Artusi’s 19th century cookbook, Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well, the father of Italian cuisine wrote “Don’t think I’m pretentious enough to teach you how to make meatballs. This is a dish that everybody can make, starting with the donkey.”

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

It was in the New World kitchens of Italian immigrants that the traditional polpette was fortified with breadcrumbs, cheese, and herbs, and anointed with marinara sauce, the lifeblood of this new cuisine. Over 4 million Italians arrived in the United States between 1880 to 1920, the vast majority from the impoverished South. Where back in the motherland they had been spending up to three quarters of their income on food, here in America it was more like a quarter. “With more money came more food,” writes Shaylyn Esposito in Smithsonian. “Women went from scraping to put food on the table to striving to be the best cook in the neighborhood.”

It wasn’t long before the meatball had secured its status as the unexpected emblem of this burgeoning culture, serving as “a bridge between the Italian-American enclaves and the mainstream diet of the United States,” as John Dickie writes in Delizia! The Epic History of the Italians and Their Food. But as it grew in size—and the ratio of bread to meat tipping precipitously fleshward—the meatball became less a symbol of immigrant thrift and largesse than of ethnic gluttony. As Mariani noted, “One need only recall the hilarious Alka-Seltzer TV commercial years ago depicting an actor doing a dyspeptic number of takes of eating a big meatball and saying the line, ‘Mamma Mia, that’s a spicy a-meat-a-ball!’”

Since that commercial first aired over fifty years ago, Italian-American cuisine has achieved a ubiquity that would have once seemed unimaginable. Today, pizza regularly tops polls of Americans’ favorite foods, Olive Garden is the nation’s most popular restaurant chain, and chefs like Mario Carbone and Rich Torrisi have elevated red-sauce cooking to Michelin-star status. Pete Wells saw this coming in 2012: “Mr. Torrisi and Mr. Carbone are Italian-Americans who, once they had a restaurant of their own, decided to cook what is a kind of soul food for them and for millions of other Americans. Even those with no Italian ancestors.”

When Wells was imaging $95 meatballs at the Four Seasons, he could hardly have foreseen that a dozen years later Carbone and Torrisi would be running the show in the Four Seasons old space. For the record, there are no meatball parms on that menu; not every dish is served by fine dining technique. What makes a great meatball sandwich isn’t the quality of the beef, or, in the words of Wells, the addition of shaved white truffle. It’s in the blend of various cuts of ground meat, and the proper proportions of bread and milk and cheese and alliums and herbs, and the melding of cheese, meat, bread, and sauce. It’s in the care and the craft, and the kinds of secrets that had to survive being passed down from generation to generation.

Last night I decided to try my hand at making proper Italian-American meatballs for the first time. The results were revelatory. I went with the recipe for “Mario’s Meatballs” from Mario Carbone, having no idea how much labor goes into the creation of something so seemingly simple. The recipe calls for a mix of veal, beef, and sweet Italian sausage. Bread soaked in whole milk. Sauteed garlic, onions, and parsley. Salt and pepper to taste. By the time the meatballs were ready, I was starving, the New York Yankees had lost, and I was in need of some serious comfort.

How many disappointed Yankees fans over the decades have consoled themselves after a tough loss with a bowl of homemade meatballs? And how many residents of Wooster Street in New Haven, Atwells Avenue in Providence and Salem Street in Boston have been similarly soothed? We’re all part of the same continuum, extending back through those first Italian migrants to America and the polpette of their old world forbears, all the way back to Apicius in the Roman empire, and beyond. The Italian meatball had to be filtered through an American immigrant sensibility before it could conquer the world. As Pete Wells noted all those years ago, “Who cares what they do in Bologna? This is Mulberry Street.”

-

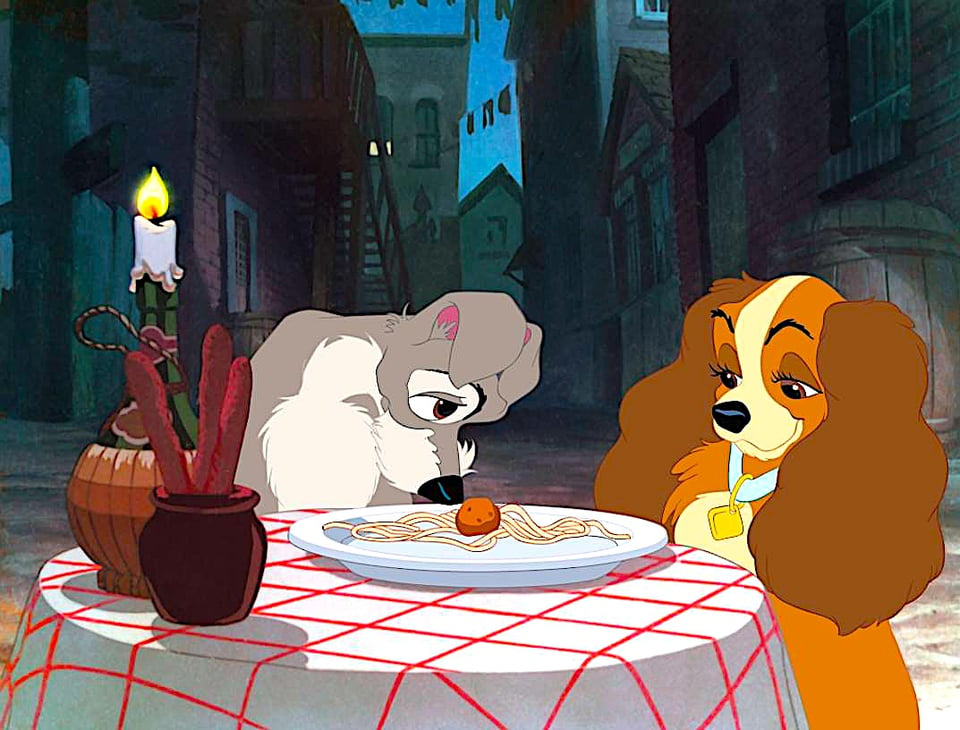

Dump the mozzarella and layer on parm. Also, whole meatballs are difficult to eat in a sandwich unless you believe in the five-second rule and are clear of hungry dogs. Cut in half allows for the sandwich to be pressed by machine or man.

-

Meatballs are just something I can't get enthusiastic about in any presentation. My partner loves a good meatball, so I keep trying them occasionally in different restaurants etc., but meh... Partly, it's texture I think, but mostly I just find them a bit bland.

Add a comment: